This column introduces an index identifying how much shocks to industrial production in one country spill over to other countries. Since September 2008, the index has jumped higher than ever – countries are pulling each other down. It argues that this reinforces the case for global action and calls for coordinated policy actions by the G20.

What started in the US as the subprime mortgage crisis in 2007 has since been transformed into a severe financial crisis for all major advanced and emerging economies. While it is too early to decide whether the global financial crisis had already reached its climax, it is by now certain that it will have a devastating effect on the global economy at least throughout 2009.The global economy is facing the threat of the worst recession in decades, perhaps the first truly global recession.

Recently there have been several studies focusing on past recessions, along with the episodes of financial crises since the Second World War (see Claessens, Kose and Terrones 2008, and Reinhart and Rogoff, 2009). By providing a careful and systematic study of the past crises and recession episodes, these papers contribute to a better understanding of the current global crisis and recession episode as well as the appropriate policy response.

However, because these papers do not study the current episode along with the past, such studies have limited scope in helping us understand how the current crisis and the recession differ from those prior. Instead, we need new studies that shed more light on the current episode using the most recent financial and real sector data.

International business cycle spillover index

In a recent paper (Yilmaz 2009), I study the statistical properties of business cycle spillovers among major industrialised countries. In my study I adopted the spillover index methodology, recently proposed by Frank Diebold and I (Yilmaz and Diebold 2009), for the analysis of stock return and volatility spillovers across stock markets around the world. The Diebold-Yilmaz volatility spillover index, updated on a weekly basis, captures how fast investors’ fears build up and spread across markets during times of major financial crises.

I apply this approach to the seasonally adjusted industrial production indices for 6 industrialised countries (France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US) to study business cycle spillovers amongst these countries.

The methodology basically distinguishes between idiosyncratic shocks to each country’s industrial production and the spillover of shocks across countries. When an idiosyncratic shock hits industrial production in a country, it potentially can spill over to other countries. When a shock is common to all countries, it affects their output simultaneously and therefore is treated as a country-specific shock for all countries rather than a spillover.

The spillover index framework allows one to identify how much shocks to industrial production in each of the countries considered affect the industrial production in other countries over time. It is quite simple to implement. For each five-year sample window, I obtain a single index value between 0 and 100, which describes the share of shocks to industrial production due to spillovers.

The time-variation in spillovers is potentially of great interest, because the intensity of business cycle shocks as well as transmission of these shocks across countries is likely to vary over time. Rolling five-year sample windows over time and calculating the spillover index for each window, I allow the spillover index to capture any possible time variation in cross-country effects of business cycles since 1958.

Business cycle spillovers since 1958

The spillover index is presented below. Monthly updates are available online.

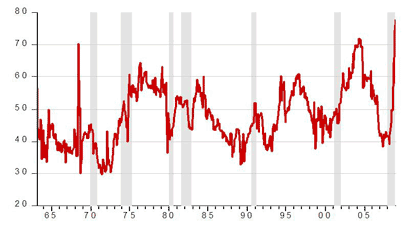

Figure 1. Diebold-Yilmaz International Business Cycle Spillover Index for G6 Countries

Note: Vertical axis is percentage share of shocks due to spillovers. Series constructed from five-year rolling windows. Shaded areas denote US recessions.

There are several important results of the analysis. First, the spillover index indeed varies substantially over time. Second, the spillover index tends to increase especially during and immediately after recessions, but also during some, but not all, expansion episodes. Finally, the most rapid and significant increase in the spillover index is observed since September 2008, attesting to the fact that in the current episode major industrialised economies are pulling each other down at an unprecedented rate.

Consistent with the first result, there is no upward or downward long-run trend in the spillover index. The spillover index fluctuates over time, and the band within which it fluctuates moves slightly upwards since the current wave of globalisation had started in earnest in the late 1980s.

From 1989 onwards, the spillover index follows three complete cycles. It is interesting to note that each time the cycle lasted longer than the previous one, with an increased bandwidth. During the first cycle, which lasted from 1989 to the end of 1992, the index fluctuated between 33% and 52%, while in the second cycle (1993 to 1999) the index fluctuated between 37% and 61%. Finally, during the third cycle that lasted from 2000 to 2007, the index fluctuated between 41% and 72%.

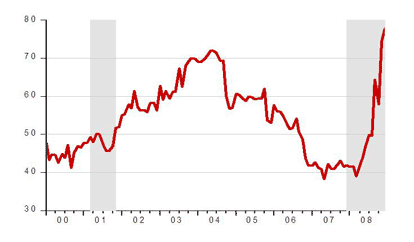

Figure 2. Diebold-Yilmaz international business cycle spillover index for G6 countries since 2000

As the US economy started to lose pace since 2005, the German, Japanese, French and Italian economies gained momentum and grew faster in 2006 and 2007. However, their growth momentum was rather weak and therefore could not generate a pull factor for other countries. As a result, production spillovers among the six countries declined sharply after 2005, with the index touching a low point at 40% in mid-2007 and staying around 40% until the end of the first quarter of 2008. From March through August 2008 the index fluctuated between 40% and 50% level.

Spillovers since September 2008

Finally, we can now turn our focus to the most important part of the spillover plot, namely the recent behaviour of the index since September 2008. The index jumped the most, from 50% to 64%, as the observations for September are included in the sample. After a slight decline to 60 in October, the index again jumped to 76% in November and to 78% in December, reaching the highest level since 1958.

The behaviour of the index during the current episode is in stark contrast with its behaviour in past recession episodes. It has increased close to 30% in a matter of four months (September through December). During the worst global recession of the post-war era – following the first oil price shocks – the spillover index recorded an increase of similar magnitude (30% to 64%) over the course of four years (1972 to 1976).

This jump in the index is an indication that countries are pulling each other down. In my research paper, I also report the directional spillovers across G6 countries. It is clear that the US is leading the way in the current recession. That means the shocks first take place in the US and spread to other countries. Other countries appear to be net recipients of shocks transmitted by the US.

Coordinated policy action is the only way out

I will update the business cycle spillover index in a few days time as the January industrial production data become available for all six countries. The index is likely to increase further, but even if it does not, the qualitative results are very unlikely to change. The spillover plot as of December 2008 shows how current global recession starkly differs from past recessions. Since the collapse of Lehman Brothers, in a matter of four months all major industrialised economies of the world are pulling each other down, with the US playing a leading role.

There is a desperate need for coordinated policy action to stop the free fall in industrial output around the world. G20 countries should agree to increase the size of fiscal stimulus packages and coordinate the way these policies are implemented. Obviously, these policies cannot be expected to have full impact unless the US government comes up with a feasible plan to clean up the balance sheets of its banks from toxic assets.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply