The US economy shifted into an interesting middle ground in recent months. The broadening of the manufacturing recovery into activity more generally, coupled with sustained growth in that bulwark of the US economy, consumer spending, supports a stream of data increasingly suggestive of a – gasp – sustainable recovery. To be sure, doubters remain. On the more pessimistic side, via Bloomberg:

The U.S. jobless rate may rise above 10 percent at the end of the year and the contraction in consumer credit will persist, said David Rosenberg, chief economist of Gluskin Sheff & Associates Inc. in Toronto.

“I think we’ll finish the year above 10 percent,” Rosenberg said in an interview with Tom Keene on Bloomberg Radio. “The credit contraction continues unabated in the household sector.”

Economic growth is being fueled by the government’s $787 billion stimulus program, which has been offsetting slumping demand, Rosenberg said. “Final sales lag far behind,” he said. “There’s been no income growth in the personal sense in the past year.”

Yes, there are indeed enough warts on the US economy to make uncharitable comparisons to the skin of a toad. Chief among those, in my mind, is the ability to make a smooth pass off from federal stimulus to other sectors later in the year. Add to that list still tight credit conditions, ongoing deterioration in commercial real estate, and a housing market that looks to remain subdued by another wave of foreclosures (although I tend not to fear foreclosures so much in general, viewing them as an effective mechanism to clean household balance sheets). But even putting all those things together, what appears to be emerging is an economy reverting back to trend growth, maybe a little above, maybe a little below.

And therein lies the rub, the problem that leaves policymakers in something of a quandary. Trend growth just isn’t good enough. Trend plus one percent isn’t good enough. Of course, not anywhere near the more apocalyptic visions of the most pessimistic procrastinators, but far short of the fable V-shaped recovery of Floyd Norris:

The American economy appears to be in a cyclical recovery that is gaining strength. Firms have begun to hire and consumer spending seems to be accelerating.

That is what usually happens after particularly sharp recessions, so it is surprising that many commentators, whether economists or politicians, seem to doubt that such a thing could possibly be happening.

Norris apparently believes that we can’t see the truth on the strength of the recovery because we have forgotten the experience of the 1980’s:

But there are, I think, a number of reasons for the glum outlook that are unrelated to the actual economic data.

First, the last two recoveries, after the downturns of 1990-91 and 2001, were in fact very slow to pick up any momentum. It is easy to forget that those recessions were also remarkably shallow. If you are under 45, you probably don’t have much recollection of the last strong recovery, after the recession that ended in late 1982….

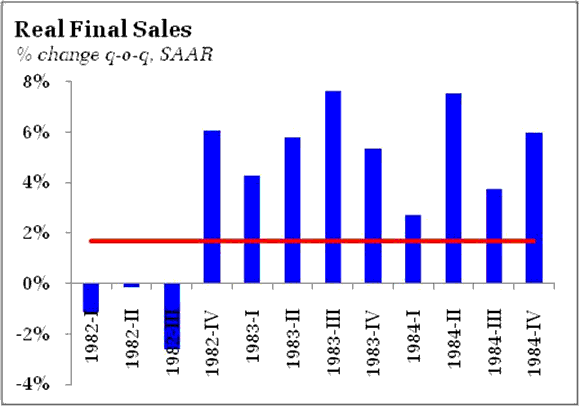

Goodness, even a cursory look at the data would dispel the myth that the current episode bore any familiarity with 1982. Absent the inventory correction, the 5.6% gain in 4Q09 GDP looks paltry by comparison:

For the nine quarters beginning in 4Q82, real final sales growth averaged more than three times the 1.7% rate (red line) of the final quarter of 2009, the blowout quarter for the V shape optimists. And, arguably, this even understates the domestic strength of the mid-80’s recovery as the GDP figures were lessened by a surging trade deficit. (Free Exchange continues the Norris critique here.)

In short, yes, given that the US economy has been growing now for three quarters, and is most likely to grow for the next three quarters, room for optimism is surely growing as well, something the pessimists need to accept, lest they fall into the trap of incoherent mumbling for the five years until the next recession provides them with an “I told you so” opportunity.

Where the pessimists have room to complain, as I am wont to do, is on the employment issue. Even the most more optimistic forecast of former IMF Chief Economist Michael Mussa is not sufficient to drive rapid improvement in the labor market. Again, think of a real V-shaped recovery like the mid-80’s. Hence the widespread disappointment with the March labor report. On the surface, the numbers were not terrible. Subtract out, however, the private and Census temporary workers, adjust for the fact that this supposedly represented a “bounce” from the weather impacted February report, and then recognize that the US economy has been growing for three quarters. Then you start to think that this is a better report, but not good enough to alleviate the pain in the labor market anytime soon. But it is not bad enough that anyone is eager to commit to additional stimulus, almost guaranteeing a continuation of the status quo, a job market that will not recoup lost jobs for years, leaving perhaps an indelible mark on a generation of workers.

Expectations of persistent labor market weakness – given that even optimistic forecasts fall well short of the V-shaped recovery bar – leaves the Federal Reserve in a holding pattern regarding their key policy rate. Calculated Risk notes:

For some reason, market participants keep thinking the Fed will raise rates soon (last summer it was by the end of 2009, this year it was by summer).

The reason is that market participants lack the option of betting on a reduction of rates. Only one way to bet. This, of course, is why the Federal Reserve has a challenge trying to communicate the lack of policy meaning behind changes to the discount rate. Every action, every official utterance is subject to analysis regarding one thing, the eventual end of the zero rate policy. As CR notes, however, Fed officials – with the exception of Kansas City Federal Reserve President Thomas Hoenig – do not appear predisposed to raise rates in the near term.

The expectation – and so far realization – of subpar labor market outcomes leaves monetary policy steady for the time being. How much improvement do we need to see before policymakers more quickly move in the direction of tightening (which, by the way, will likely begin with quantitative tightening rather than rate tightening). Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke laid down an interesting marker in a speech last week:

More than 40 percent of the unemployed have been out of work six months or longer, nearly double the share of a year ago. I am particularly concerned about that statistic, because long spells of unemployment erode skills and lower the longer-term income and employment prospects of these workers.

One can infer that Bernanke would prefer to see the share of long term unemployment drop dramatically prior to a clear policy shift. One can also infer the possibility of a measurable, albeit, small, structural increase in the unemployment rate. From the soon to be departing Vice Chairman Donald Kohn:

An ongoing concern in this recovery is whether unemployed workers may experience unusual difficulties in re-entering the workforce. The duration of unemployment has been exceptionally long in this business cycle, a development that could erode worker skills and decrease re-employment probabilities. In addition, it may take some time for those who are unemployed to move or retrain for the new jobs that the recovery will bring. For these and other reasons, part of the increase in unemployment over the past two years may be structural, and this part would tend to reverse only slowly.

Even if a portion of the rise in unemployment is structural, however, most appears to be cyclical, suggesting that the economy is operating well below its productive potential. This conclusion is supported by other measures of slack, such as capacity utilization in manufacturing, and by the ongoing deceleration in wages and prices.

Finally, the other impediment to policy tightening is the inflation outlook. The Fed appears to have abandoned its earlier flirtation with the notion that deflationary pressures can be dismissed as a consequence of the housing downturn. From the most recent minutes:

Participants referred to a wide array of evidence as indicating that underlying inflation trends remained subdued. The latest readings on core inflation–which exclude the relatively volatile prices of food and energy–were generally lower than they had anticipated, and with petroleum prices having leveled out, headline inflation was likely to come down to a rate close to that of core inflation over coming months. While the ongoing decline in the implicit rental cost for owner-occupied housing was weighing on core inflation, a number of participants observed that the moderation in price changes was widespread across many categories of spending. This moderation was evident in the appreciable slowing of inflation measures such as trimmed means and medians, which exclude the most extreme price movements in each period.

Still, Kohn at least sees little room for additional downward pressure on inflation:

With only a moderate recovery likely on tap, I expect unemployment to come down only slowly from its currently elevated level. Although the persistent high level of unemployment will tend to restrain inflation further, the effect of resource slack on inflation does not appear to be as great as some previous episodes might have led us to expect. The difference is that inflation expectations now appear to be much more firmly anchored than they once were, probably reflecting the extended period of low inflation that we have experienced and a credible monetary policy directed at sustaining this performance. I anticipate that inflation will remain low for a while, with core PCE inflation not likely to fall much further from the subdued pace I cited a few minutes ago.

Which leaves him, like I suspect the FOMC in general, still inclined to look only toward a tightening of policy in the future, not any additional loosening that would arguably be appropriate given the current forecasts for both unemployment and inflation.

Bottom Line: It is difficult to argue with the steady stream of data that increasingly suggests the recovery is sustainable. It is also difficult to argue with the proposition that even if sustainable, the recovery is disappointing from the jobs perspective. That disappointment, couple with the lingering concern that the economy will not sufficiently transition from fiscal stimulus to sustain the meager labor market improvements to date, leaves monetary policy on hold for the foreseeable future. The transition from fiscal stimulus would be greatly improved if we could reliably expect the external sector to pick up the slack. And the economy remains as risk to that familiar gremlin, the exogenous shock. I find myself a bit more concerned than Jim Hamilton on the risk from oil prices. But both oil and external trade are issues I intend to follow up with later in the week.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply