The elasticity of housing supply is the effect on the flow of home building (measured as a log change — think of it as a percentage change) of the inflation-adjusted purchase price of housing (also measured as a log change).

The elasticity has long been studied in economics; one of the seminal studies was published by Professors Topel and Rosen in 1988.

The most recent (2000-2005) housing boom was a boom in both housing prices and construction — was it a movement (albeit, further) along the same sort of supply curve as in previous housing cycles?

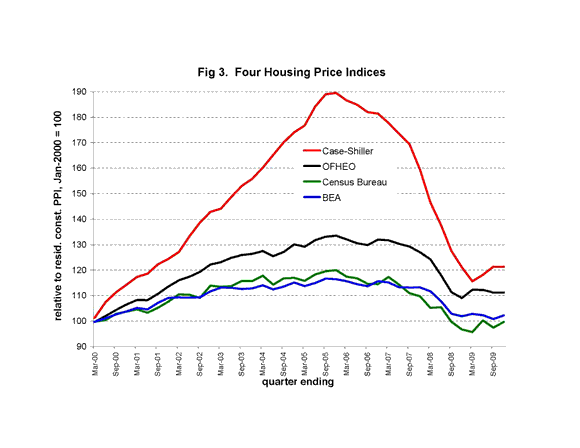

Unfortunately, I have noted before that various housing price indices disagree widely about the magnitude of the housing price boom. The Case-Shiller index (adjusted for general inflation as measured by the PCE deflator), says that housing prices were 0.56 log points (about 75%) .17higher in 2005 than they were in 2000. The OFHEO index says 0.27 log points. The Census Bureau quality-adjusted index of the selling prices of new homes (the index used in the Topel-Rosen study) says 0.17 log points. The BEA price index for new residential structures says 0.15 log points.

Because the indices give such different estimates of housing price changes, they would give equally different estimates of the supply elasticity. So, in order to answer the question, it is crucial that I stick with the index used by Topel and Rosen.

Real residential investment per capita increased 0.24 log points. So that implies a supply elasticity of 1.4 for the period 2000-2005.

Topel and Rosen found significant lags in the response of investment to housing prices, whereas the boom and bust since 2000 interestingly show housing construction and housing prices to change direction in essentially the same month.

Putting that aside, Topel and Rosen find a 1.0 supply elasticity with respect to a housing price elevation that lasts one year, a 1.6 elasticity for a 4-year elevation, and a 1.7 elasticity for a 8-year elevation. So that looks pretty close to what happened in the recent boom, occurring after Topel and Rosen wrote.

[Technical note: to adjust for trends, Topel and Rosen put a linear (NOT exponential) trend in a level-of-investment regression. That is not appropriate here — would be very sensitive to which years were included — so I normalized investment by population]

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply