In case you needed a reminder that the nascent recovery in the United States is, well, nascent, yesterday’s employment report should do the trick. You can find a discussion of the ins and outs of the report at Calculated Risk (to give but one example), but overall the news was a mixed bag of a little better news than was expected (the fall in the unemployment rate even as the labor force participation rate rose), a little worse news than was expected (the net three-month loss in payroll employment), and some relatively bad news that was largely expected (the large downward revision in employment growth for the period April 2008 through March 2009).

Certainly, the employment picture is a lot better than this time last year, but it is still a good distance from what anyone would regard as “cheery.” Hence the focus in the Administration’s latest budget proposal on programs aimed at job creation.

Over at the Becker-Posner blog, Gary Becker strikes a skeptical chord about at least one element of the Administration’s package, the element related to subsidies designed to spur job growth in the small business sector. Despite his reservations about the specific tax credit in play, Professor Becker is fully on board with the proposition that “smaller businesses are an important source of innovation and progress.” One particular observation in the Becker post caught my eye:

“The US is tied for first place [according to estimates by the World Bank] on the ease of employing workers. It is much easier for American small and medium size business to reduce their employment during bad times than it is for similar-sized companies in Europe, Latin America, or India. This helps explain why employment fell, and unemployment rose, more sharply during this recent recession in the US than in say Germany, Italy, and many other countries that have much less flexible labor markets, even when other countries experienced larger recession-induced falls in GDP.”

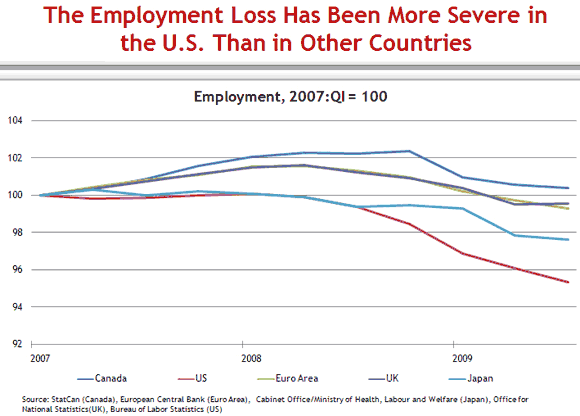

The outsized negative employment effect in the United States relative to most other developed countries is a striking feature of the labor market data of the past two years. The following chart shows the trajectory of employment in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and the Euro Area since December 2007 (the beginning of the U.S. recession).

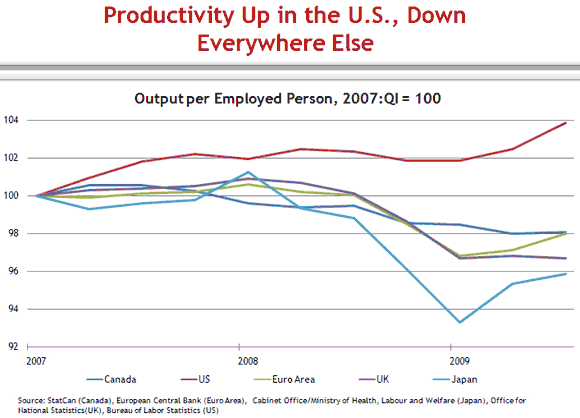

The outsized drop in employment in the United States is the mirror image of another crucial feature of the last several years: outsized productivity growth in the United States.

What are we to make of the productivity gains in the United States relative to other countries? Does this difference merely reflect labor hoarding in other countries, implying that the productivity levels will become more consistent among advanced economies as employment recovers in the United States? Or is there something more fundamental at play, as Professor Becker seems to imply? Have businesses in the United States found ways to permanently enhance efficiency, locking relatively high productivity growth—and perhaps a slower recovery in employment levels—into the future?

Good questions, all.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply