Back in 2005, Alan Greenspan complained of a ‘conundrum’: The fact that long-term interest rates were refusing to rise, despite a sharp increase in short-term rates. At the time, there were all sorts of explanations given. In retrospect, this puzzling behavior of the financial market was a sign of deep problems.

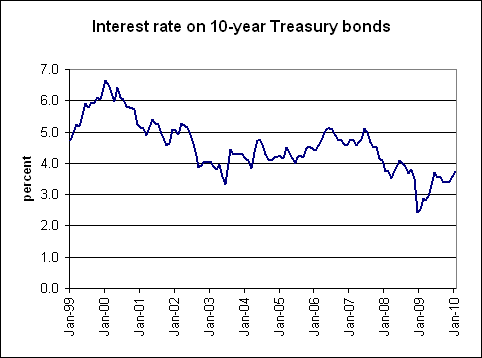

Right now, we are facing the conundrum, part II. The news is dominated by the massive gov’t budget deficits, which stretch as far as the eye can see. But despite the incredibly large borrowing needs, Washington is actually raising money at lower rates than it did in 1999 and 2000, when the federal government was running a surplus. Here are the two relevant charts. First, the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds.

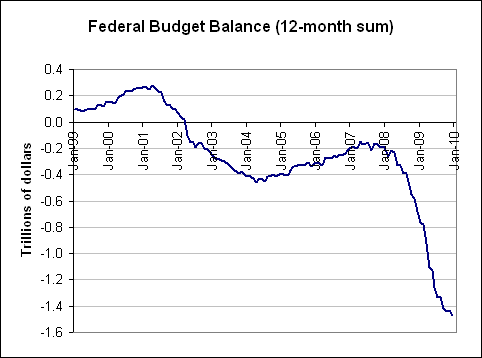

And here’s the change in the federal budget balance, as a 12-month sum. We can see how small surpluses turned into stunning deficits.

These are the sort of charts which are frustrating to deficit hawks and professors who have to teach macroeconomics. There seems to be no easy and straightforward link between budget deficits and interest rates

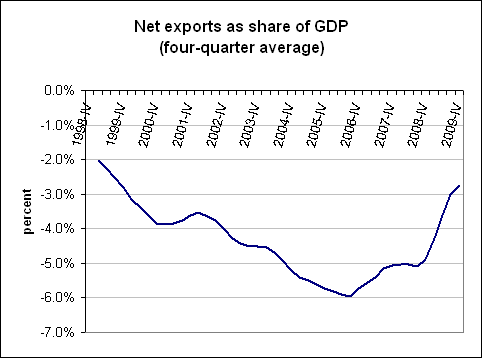

So let’s go looking for other reasons. First, inflation is about at the same level as it was in 1999 (the consumer inflation rate in the year ended December 1999 was 2.7%, compared to 2.8% in the year ending December 2009). Second, net exports as a share of GDP are roughly about the same level as they were in 1999 and 2000, suggesting that the U.S. has about the same need to borrow from overseas.

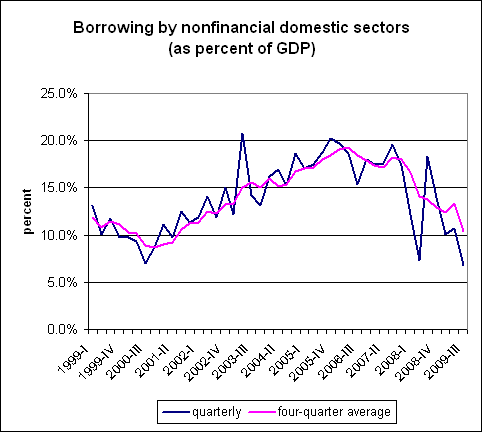

Is it possible that the federal government is getting such a good rate because the rest of the economy is not borrowing? Here’s a chart of borrowing by all nonfinancial sectors–consumers, nonfinancial business, state and local governments, and the fed. Measured as a share of GDP, borrowing is still roughly where it was back in 1999 and 2000. (I’ve given both the quarterly and the smoothed charts).

So what the heck is going on here? It could be that the U.S. government still counts as the only safe investment out there, even with the big budget deficits. Possible, but that depends on highly myopic investors. It could be that the demand for funds globally is low. Or it could be that the bond market is trying to tell us that long-term expectations for growth are low.

It’s a conundrum.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

i thought interest rates were low because the fed is buying the fed/debt with money that it is printing. this is what it did in WWII. part of the reason the fed doesn’t want to be audited is because it would have to reveal how much fed/debt it is purchasing with printed money. i was under the impression that this was well known.