Before I begin, I want to tell all of my friends in Japan that I have a great love for their country. I have not traveled much, but if I were to travel abroad, Japan would be my first choice. Plus, I have many friends in Kobe, Japan.

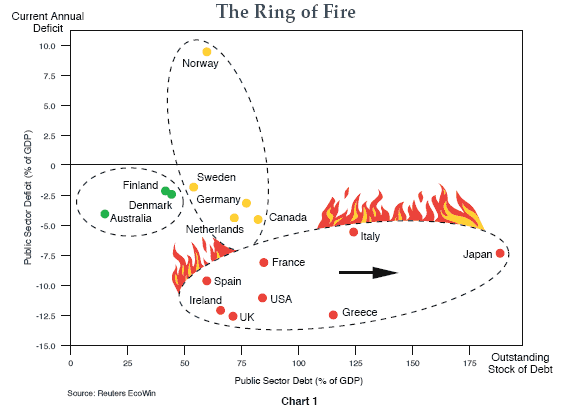

Japan is at the leading edge of the demographic wave where many developed countries have a shrinking population. But beyond that, Japan has high government budget deficits and a very high government debt. Consider this graph from Bill Gross’ latest missive:

Japan is in the awkward spot of having high government debt, though much is internally funded, and is still running high government budget deficits.

What a mess. I happened across a blog I had never seen before today, and it gave a simple formula for when government debts would tend to become unsustainable. It was analyzing Greece, but I looked at it and said to myself: “What about Japan?”

The main upshot of the equation in the article about Greece is that you don’t want the rate your government finances at to get above the rate of GDP growth. If so, your debt will increase as a fraction of GDP, even if your deficits drop to zero.

So, what about Japan? Can we say two lost decades?

(click to enlarge)

Oooch! 0.2%/yr average growth of nominal GDP?! That stinks. But here is what is worse. The Japanese government finances itself at an average rate of 0.6%. The debt is walking backward on them unless GDP growth improves. No wonder S&P has put Japan on negative outlook.

Japanese interest rates could rise. Like the US. Japan has an average debt maturity around 5.5 years. Unlike the US, 23% of its debt reprices every year, which makes them more vulnerable to a run on their creditworthiness.

Here are three more links on the Pimco piece, before I move on:

- An eye-catching quote…

- “UK gilts resting on a bed of nitroglycerine”

- Gross on Gilts: ‘On a Bed of Nitroglycerine’

We can think of central banks as equivalent to a margin desk inside an investment bank in the present situation. Though I can’t find the data on the web, what I remember from the scandal at Salomon Brothers that led Buffett to take control, there was a brief loss of confidence that led the investment banks margin desk to raise the internal borrowing rate by 3-4% or so. Within a day or so, the trades expected to be less profitable of Salomon were liquidated, and Salomon had more than enough liquidity to meet demands.

But this is the opposite situation: what if the margin desk were to drop the internal lending rate to near zero? Risk control would be hard to do. Lines of business and people get used to used to cheap financing fast. If it were just one firm that had the cheap finance, say, they sold a huge batch of structured notes to some unaware parties, it would be one thing, because after the easy money was used up, the margin rate would revert to normal, and so would business activities.

But let’s expand the paradigm, and think of the Central Bank as a margin desk for the nation as a whole. Pre-2008, before the Fed moved to less orthodox money market policies, this would have been a more difficult claim to make, but the claim could still be made.

Pre-2008, the Fed controlled only the short end of the yield curve, which, with time, is a pretty powerful tool for making the economy rise and fall. Short, high-quality interest rates move virtually in tandem with the Fed funds rate, but during good times, with the Fed funds rate falling, economic players seek to clip interest spreads off of longer and lower quality fixed claims, causing their interest rates to fall as well, with an uncertain timing, but it eventually happens.

And when Fed funds are rising, the opposite happens — funding rates for those clipping interest spreads rise, and the expectation of further rises gets built in, leading some to exit their trades into longer and riskier debts, which makes those yields rise as well, with uncertain timing, but eventually it happens.

I like to say that every tightening cycle ends with a crisis.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply