Insurance is probably the most complex industry as far as accounting goes. Why? When you sell the policy, you have a vague idea of what the costs will be, and when those cash flows will occur.

That leaves room for a wide variety of games as far as the accounting goes. Because hitting operating return on equity targets is often the “be all” and “end all” of management reporting, one of the holy grails was taking capital losses and turning them into operating income. Net result on income is zero, but it looks like you are making a lot of returns off of operations.

At one company that I worked for, the new CEO want to great pains to declare how ethical the new CFO was. I murmured to my boss, “Not ethical, but clever.” He gave me a smile. She had pulled that very trick, and if one reconciled the Statutory and GAAP accounting, the chicanery was obvious.

At AIG, my managers were quite concerned about what went above the line and below the line. If an accounting item didn’t figure into net income my managers didn’t care about it, even if it diminished shareholders equity.

As an investor, this made me skeptical about income statements. But if you don’t have an income statement, what do you do to estimate profitability?

Well, you could look at the change in tangible net worth due to common shareholders, and add back dividends, including the value of spinoffs, and net money spent on buybacks. That is what a shareholder earns, in book value terms. Back when I was an analyst of the insurance industry, there were companies run by value investors that would present their returns that way showing the the growth in fully converted book value over time. In a sense , Berkshire Hathaway does that as well, but it doesn’t pay a dividend, so it is simply the increase in book value.

In the short run the market is influenced by net income due to common shareholders. But there is a difference between the two measures of income, and I call the difference “cram.” Cram is the amount of extra income reported through the income statements that does not makes its way through the balance sheet.

That said, I have another measure that I nickname “jam.” Jam is the amount of money gained/lost from buying back stock. In general, when companies buy back stock they dilute value for investors. Better to retain and reinvest.

How do I know this? I have been working on an accounting quality model, which is still a work in progress. An aside, I have had my share of calls from consultants who tell me they have an earnings quality model that covers the whole market. When they call me I ask them how they analyze financial companies. I get the intelligent equivalent of a shrug. The reason is that accruals on the financial statements of industrials and utilities are quite similar, but for financials, they are quite different.

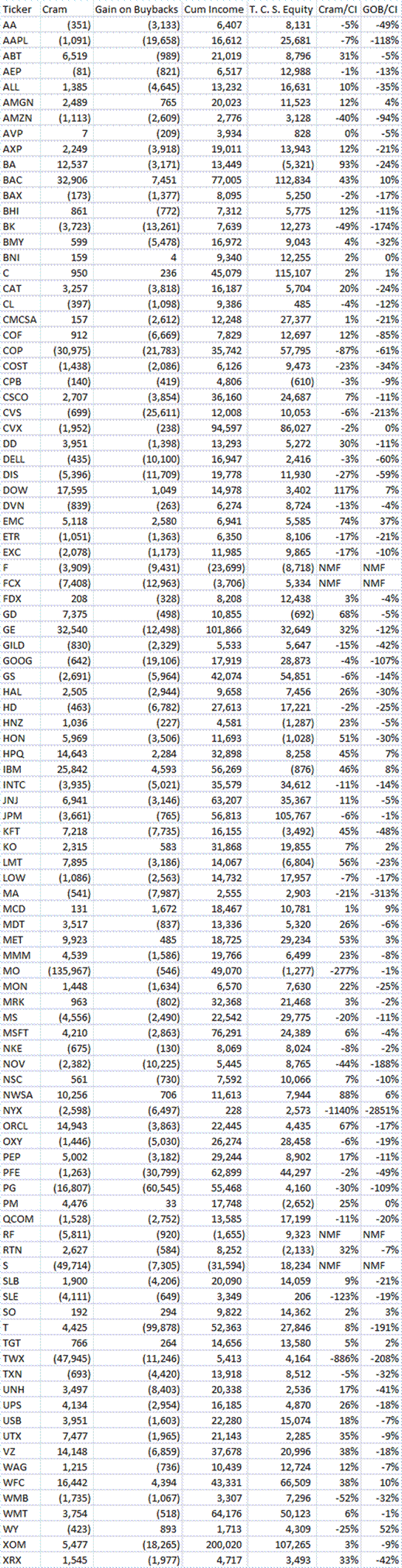

Here are some of the results of my model on the S&P 100:

The data covers the last 4 3/4 fiscal years. Why did I use fiscal years? Because data capture with companies is most complete at fiscal year ends, when they file their 10Ks.

What did I find? In general, most companies lose money off of buybacks, whether it is 24% of cumulative net income, or 32% of final tangible net worth. Individual company performance varies a great deal. More surprising to me was that cram on average was only 1% of cumulative net income. Maybe GAAP isn’t so bad on average after all. But averages conceal a lot of variation — I would not want to own companies that lose a lot of money off of buybacks, or those that inflate net income versus growth in tangible book.

If buybacks ceased, companies might have a lot of slack assets on hand. I know that companies keep themselves slim to avoid takeovers, A large amount of slack assets invites others to come in and buy the assets to manage them. Still, it seems that most buybacks waste the money of shareholders. This seems to be another example of the agency problem, where managers take an action that benefits them, but harms shareholders.

I would be negative on both cram and jam. Good companies don’t report earnings in excess of what shareholders obtain, and they don’t buy back stock except when it is cheap.

Disclosure: long ALL COP CVX ORCL PEP

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply