In this morning’s Breakfast With Dave newsletter, Gluskin Sheff Chief economist David Rosenberg talks about how in today’s economy, growth and the credit market remains stagnant. As a result, many businesses are finding their operations constrained by cash flow concerns.

In this morning’s Breakfast With Dave newsletter, Gluskin Sheff Chief economist David Rosenberg talks about how in today’s economy, growth and the credit market remains stagnant. As a result, many businesses are finding their operations constrained by cash flow concerns.

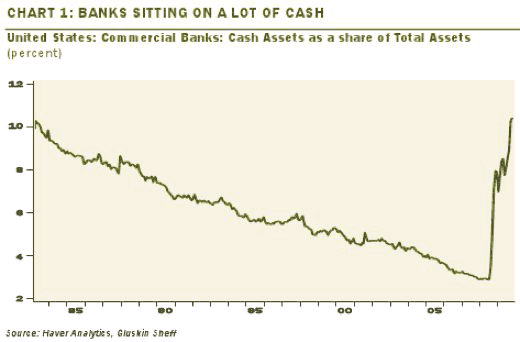

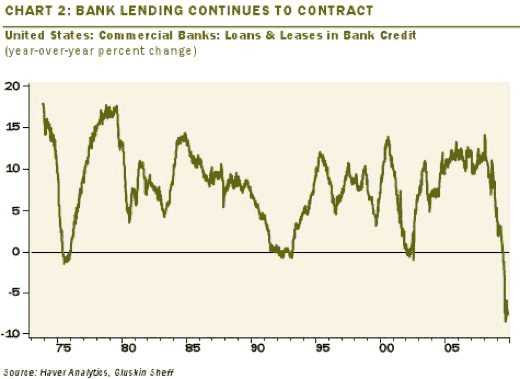

Gluskin Sheff: “Look at the charts below and you will see how little effect the policy stimulus is exerting leaving the government continuing with demand-growth policies, such as extended and expanded housing tax credits, and the Fed, Treasury and the FHA doing all it can to keep the credit taps open … and for marginal borrowers at that. So the charts below show what, exactly? That the transmission mechanism from monetary policy to the financial system and the broad economy is still broken fully 2½ years after the first Fed rate cut. Cash on bank balance sheets as a share of total assets is at a three-decade high.

Bank lending to households and businesses has contracted more than 7% from a year ago, an unheard-of rate of decline unless you want to go back to Japan in the 90s or the U.S.A. in the 30s.

According to Rosenberg, with money velocity remaining at very depressed levels, deflation will be the principal risk in 2010.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

This is also why the supply chain is deteriorating (see article below). How long before the Brown Shirts are in the streets? The problem is the West Coast Hotel v. Parrish “scrutiny” regime. Supply chain, like employment, enjoy only minimum scrutiny. So what can businesses do to legally enforce supply chain? That is, how can they resist the assault of fascist corporatism? They can’t. It’s more than “deflation” we have to worry about, my dear.

Risks taken in recession threaten business

By Brian Groom, Business and Employment Editor

Published: January 6 2010 00:01 | Last updated: January 6 2010 00:01

Businesses have acquired huge risks that they barely understand as the result of operational changes made during the recession, according to an in-depth study of 250 companies.

The increased risks are likely to lead to losses for many companies and insurers over the next three years, warns the report by Mactavish, a research company specialising in risk and commercial insurance, which surveyed businesses across manufacturing, construction, retailing and financial services.

The risks range from weaker supply chains to rushed product development, lower supervision levels, diversification into unfamiliar products and territories, increased contractual liabilities and low-cost outsourcing to China and elsewhere.

Many of the extra risks had not been fully disclosed to insurers, increasing the danger of insurance contracts being invalid. Sixty-five per cent of companies said they did not review how their risk was explained to insurers as part of the contract on which their businesses rely.

Insurers and brokers have also failed to address the issue, the report argues, suggesting systemic underpricing of risk and increasing the likelihood of a severe insurance market correction.

“British firms contain new risks that have not been properly understood or reflected. As a result of this, combined with existing pressures on insurers, the insurance sector and the companies it serves could be facing a perfect storm that would form another phase of the financial crisis,” said Bruce Hepburn, Mactavish chief executive.

Strategy shifts

Moving into unfamiliar product areas and territories

●Speeding up product launches, increasing the danger of failures

●Replying on a smaller number of suppliers and distribution centres

●Increased outsourcing to Asia, weakening control over quality

●Pressure to accept extra contractual liabilities in areas such as product warranties and recall costs

●Cutbacks in supervision and health and safety budgets

●Desperate bidding for contracts leading to corners being cut on quality and safety

●Finance companies facing professional indemnity, cyber-crime and shareholder lawsuit risks

He urged businesses to “wake up” and review their operational risks. There was still an opportunity to make a fuller disclosure and take advantage of low prices for cover before the “soft market” in commercial insurance ended.

In manufacturing, four-fifths of the companies interviewed, with turnovers of £50m to £5bn, said their supply-chain vulnerability had grown. Supplier failures, enforced single sourcing, reduced stock levels and cutting of excess production capacity were cited as reducing their resilience.

Few companies have analysed the risk implications of a surge in outsourcing and overseas joint ventures, the report says.

Manufacturers were also diversifying into new products and markets to maintain business during the recession, which typically increased failure rates. They also faced pressure from customers to accept extra liabilities in areas such as product warranties, recall costs, design risk and consequential loss.

Construction companies looking for new sources of work were undertaking activities that exposed them to unfamiliar risks in areas such as asbestos exposure or working in derelict buildings. “Contractors are now routinely winning bids they’re not qualified to do,” said one group health and safety manager.

Intense cost-cutting in construction had led to widespread reductions in health and safety spending and site supervision, and “suicidal” bidding practices that encouraged corner-cutting.

Retailers were vulnerable to the effects of cost-cutting by suppliers and to the consequences of sourcing from lower-cost countries where liability cannot easily be passed back. Inability to get trade credit insurance remained a problem.

“We are currently managing a very large product claim – over £10m – which came from a range of products deemed to be traditionally very low risk. We now source extensively from the Far East. We realise there is simply no prospect of getting money out of [specific Chinese suppliers],” said one retailer’s insurance director.

FT Manufacturing Barometer

FT Interactive feature: See how 59 manufacturing companies are coping with the downturn in the FT survey

Medium-sized financial services companies interviewed by Mactavish argued that their business models were robust and their activities low-risk. The report warns they may be being complacent in view of recent issues such as breach of investment mandates, negligent advice, a lack of proper due diligence and fraud claims.

PwC, the professional services firm, said: “Insurers and insurance intermediaries need to fundamentally rethink how risk is assessed, how companies are insured and how to keep pace with an increasingly complex, uncertain and fast-changing risk landscape.”

Mr Hepburn said if insurers did not tackle the issue now it would lead to volatile pricing in the next “hard market”, likely to affect areas such as business interruption, product liability and professional indemnity.

—

What You Can’t See Can Hurt You

The collapse of the economy — and many manufacturers’ key suppliers — underscores the need for improved supply chain visibility.

By Josh Cable

Dec. 16, 2009

Jim Lawton, senior vice president and general manager of supply management solutions at the Dun & Bradstreet Corp. (D&B), recalls a conversation in which he told a client’s chief procurement officer that a supplier of the client company had been slapped with an EPA violation for mismanaging radioactive material.

The chief procurement officer promptly left the room.

“He got up from the table and said, ‘Look Jim, I’m very interested in continuing this conversation — I’ll reach out to you to do it right away — but I have to go,'” Lawton explains. “That information was that critical to him, and he had no idea it was there.”

Experts say the increasing globalization and complexity of supply chains has put too many manufacturing executives in similar shoes — out of the loop when it comes to important financial, performance, legal and compliance information on their suppliers.

“We work with a lot of companies that find out about [supplier] bankruptcies months after they happen,” Lawton says. “Or they learn about them, but not in time to be able to continue to make sure they have parts coming into their facilities, and then all of a sudden they’re not able to build the product that they need to ship to their customers.”

Lawton notes that the collapse of the economy has precipitated supplier bankruptcies “in traditionally strong companies in all kinds of industries where you weren’t expecting them,” serving as a wake-up call to the importance of having real-time insight into the potential risks posed by suppliers.

“One of the lessons learned … was that we often do a very good job of looking at the creditworthiness of our customers and their ability to pay us, but we don’t do as good a job looking at the financial wherewithal of our suppliers,” says Tom Murphy, executive vice president of manufacturing and wholesale distribution for the professional services firm RSM McGladrey Inc. “It’s a very, very difficult lesson to learn.”

Still, it’s a lesson that manufacturers seem to be taking to heart. Lawton estimates that at least one-third of his clients now are taking steps to improve their supply chain visibility, compared with fewer than 5% of his clients two years ago. Tim Hanley, vice chairman and leader of Deloitte & Touche LLP’s U.S. Process & Industrial Products group, says “no one I’m working with isn’t having a fresh look at their supply chain.”

“One of the things we’re really seeing our clients do now is take on a more heightened focus on understanding all the risks in their supply chains,” Hanley says.

Those risks have been increasing over the past decade, due to manufacturers’ “relentless focus” on reducing costs in their supply chains, according to Josh Green, CEO of Panjiva, a New York City-based provider of business intelligence for global manufacturers.

“Companies, by and large, pay too much attention to the costs and not enough attention to the risks,” Green says, adding that many companies were “shocked” to discover just how vulnerable their suppliers were when the recession hit. “And so when the economic downturn did hit, very few companies had invested in and developed a robust risk management infrastructure that would have given them an early warning.”

While Green believes that companies are learning about the importance of supply chain visibility from the recession, he worries that they might be learning “the wrong lesson.”

“I think there is a danger … that [companies] are going to say, ‘Ah! We get it! There’s risk, and the risk is that suppliers will go out of business,'” Green says. “The reality is that risk is real, and it’s exacerbated in an economic downturn, but there are actually quite a few risks.”

In addition to the risk of supplier viability, manufacturers need visibility into the risks that suppliers pose to their brands — a risk that Green places under the rubric of “social responsibility.”

Manufacturers also need insight into the safety risks posed by suppliers — an issue that has been in the headlines in recent years with the recalls of a number of Chinese products due to safety and health concerns.

Another type of risk — “capacity risk,” or the risk that suppliers will not be able to meet demand — likely will become more acute as the economy recovers and demand rebounds, according to Green. Exacerbating capacity risk is the fact that many manufacturers have been focusing on reducing inventory during the recession, D&B’s Lawton points out.

“When there’s any kind of issue with a supplier, I used to have a whole bunch of inventory between me and the problem that would allow me to continue to ship to customers, and now I don’t,” Lawton says. “So now I need knowledge more quickly, and if I can make it more proactive and predictive, tell me the companies that I’m likely to have problems with.”

A Single Global View

Lawton’s conversation with the chief procurement officer mentioned at the beginning of this article illustrates the fundamental challenge facing many of the companies that come to D&B for help: How to sift through information on perhaps tens of thousands of suppliers to spot potential problems — “before they give me a whole lot of grief,” as Lawton puts it.

Lawton adds that implementing a supplier watch program, which may focus on a manufacturer’s top 100 suppliers, isn’t necessarily the answer, as “we run into a lot of companies … that keep getting nailed by the supplier that’s 150 or 500 on the list.” And supply chain executives, who are tasked with doing “more with less” these days, can’t just throw more bodies at the problem.

“If I have 75,000, 150,000, 200,000 suppliers and 200 people managing those suppliers, I can’t have them spending a lot of time with any one of them,” Lawton says. “So I really need a way to zoom in on the ones where the big problems are, know about those problems as early as I can so I can buy myself the lead time to engage with them, understand what the issues are, decide if I need to take some kind of mitigating strategy to protect myself against the risk and then execute on that strategy.”

When building a supply chain visibility system, it’s wise to start with baby steps, Lawton says.

“We typically recommend that you start with what you can do today and then grow that over time, because our experience is when you try to do these massive transformations, they have a much higher likelihood of failure,” he explains.

For many companies, a logical starting point is to establish “a single global view of everybody I do business with,” or a dashboard, that helps them understand the “interdependencies” of their suppliers, Lawton says.

“There’s a particular company I’m thinking of that has 72 different ERP systems,” Lawton says. ” … They don’t have a single view of all of those companies that ties together all of the interrelationships in terms of this company is partially owned by this company, and so risk in one is potentially setting up risk in the other.”

To form “a more complete view” of their suppliers, Lawton advises supplementing the available internal information with external information such as: suppliers’ current financial conditions, on-time deliver histories and other performance information; OSHA or EPA violations; pending lawsuits, liens or criminal charges; and whether a supplier is named in the U.S. government’s Excluded Parties List System or the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s list of companies run by suspected terrorists.

Panjiva’s Green asserts that the value of a dashboard is relative to the quality of the data being fed into it. That’s why he cautions against “relying too heavily on one data source” — such as credit reports — and suggests considering the insights of “your team on the ground that’s interacting with these suppliers” as another potential data source to add to the mix.

“If I’m getting three data points about a single company that are all telling the same story, I can be much more confident that I’m getting the right answer than if I’m just getting it from one data source,” Green says.

One final note: RSM McGladrey’s Murphy points out that supply chain executives suffering from a “10-year hangover from Y2K” should not be gun-shy about investing in software or hardware to improve visibility, as the technology available today “is significantly better than what we may have looked at in the past.” Lawton agrees, noting that many companies are opting for Web-based systems via the software-as-a-service model, which offers the advantage of rapid implementation.

“Especially over the last year, because time has been such a concern, one of the first questions we get asked is, ‘How quickly can I get this in place?'” Lawton says. “And the answer is, ‘As soon as you can get us a list of your suppliers, we can turn on the system tomorrow.'”