When even that great Keynesian pumper Paul Krugman concedes defeat, you know something fundamental has changed – and that is a belief in continued Keynesian stimulus. He used to preach a multiplier effect, which I have dissected in earlier posts, but no more; and without it, we would have to keep increasing stimulus to keep the economy alive until we cannot fathom funding it anymore. He now is urging the Fed to engineer inflation.

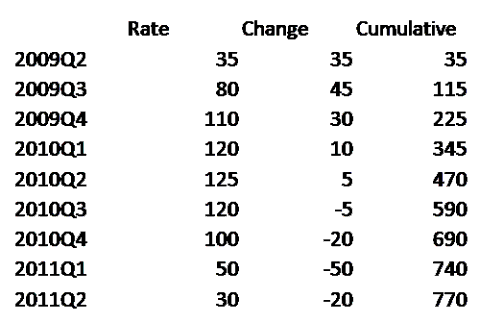

Think about this: we would have to keep increasing stimulus to keep the economy afloat. Krugman posted a table to explain how a lot of Stimulus might remain to be spent, but have no future impact on GDP growth. The table can be used to substantiate the point about increasing stimulus just to stay afloat. (Running harder and harder to stay in the same place – Alice’s Red Queen indeed!). His key metrics are the quarterly rate of spending and the quarterly change in spending, not cumulative spending. The rate adds to GDP (+/- any multiplier), but the most important metric is the quarterly change, since that adds to (or subtracts from) the reported GDP growth rate, the measure we all watch. As you can see, even with substantial Stimulus left to be spent, the Change in spending has already peaked and is going to go negative:

“Change” peaked in Q3 (see also my post Peak Stimulus), the quarter that has now been revised down to a 2.2% growth. A bit of inventory rebalancing in Q4 plus decent retail results may pop Q4 up above 3% (some predictions, such as from JP Morgan, have been for as much as 4.5%), but it is downhill from there. The quick additional “midnight” stimulus passed right before Congress rushed off to Christmas break is unlikely to have much impact, since it is poorly designed, as were the last two (this is the third stimulus, after W’s tax rebate in 2008 and the Porkulus).

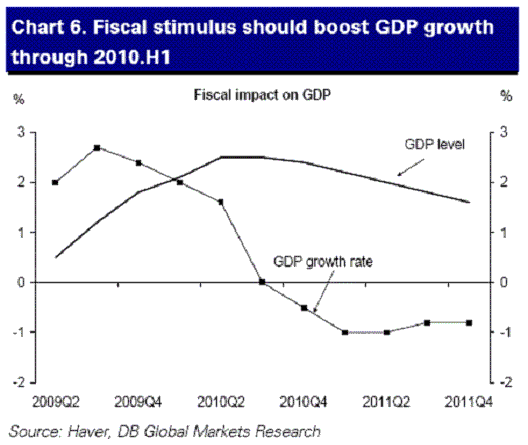

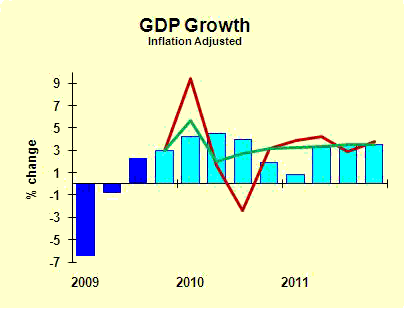

The dynamic of GDP level vs. GDP growth is well captured in this chart from Deutsche Bank:

The level of GDP is higher than it would have been absent stimulus, but is peaking in Q2 and rolling over, as growth slows and then goes negative in Q3 next year. Now, inventory restocking and private spending can change this dynamic, if they come back, at least to push off for a quarter or two that roll-over towards down again.

Until we actually have a recovery of the private economy, we remain on government life support, and will see the economy come crashing down in the W-Shaped recession as the Stimulus abates in the second half of next year.

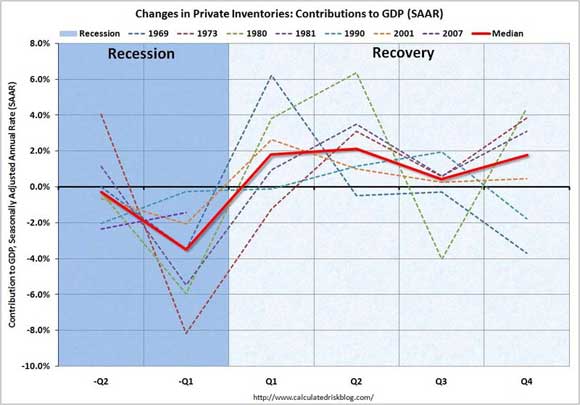

So how well is the private economy doing? Inventory rebalancing can help, but the help is transitory. This chart from CalculatedRisk suggests that historically inventories increase in the first two quarters coming out of a recession, adding about 2% per quarter to GDP growth, and then flatline:

Let’s walk through the primary components of Q4 GDP, beginning with inventories:

- Inventories: If we bottomed in Q2, we should have seen a 2% bump of inventories in Q3; we actually saw only 0.7%, after all the revisions to the Q3 number. We might see 2% in Q4, although retailers kept inventories a bit lean this year. Let’s say between 1.5 and 2%.

- Personal consumption (PCE): Given the late Xmas retail save, PCE should be pretty good in Q4; Calculated Risk estimates 1.7% growth, for a 1.2% contribution to GDP (calculated based on consumption being 70% of the economy).

- Investment: new housing dropped hard in Nov, and the tax credit for existing home sales is ending, but overall a slight positive from real estate in Q4. Business investment is moribund. Exports are increasing relatively to imports. Overall impact may be scratch.

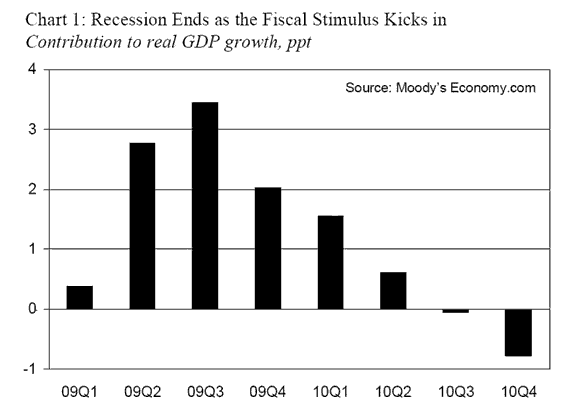

- Stimulus: The following chart would estimate a 2% contribution to GDP in Q4.

Put it together and we have GDP for Q4 = 1.8% from inventories + 1.2% from Personal spending + 2% from Stimulus + about scratch from everything else (investment, exports over imports) = 5%. Looks pretty good! Goldman Sachs sees 4% GDP, and we have noted above that JP Morgan sees 4.5%, so this back-of-the-envelope is probably too high. The last two GDP revisions suggest that it is too optimistic to assume investment and net exports to be scratch; they are likely to be negative again and lower the GDP number. This is especially so since the revisions to Q3 were much more than normal; usually the third revision is slight, whereas this one was major. As Goldman Sachs commented:

This was a much larger than normal revision for the third pass on a given quarter, knocking what once was a fairly robust 3.5% bounce down to a mediocre 2.2% (from 2.8% prior to this revision). All sectors except the trade balance — a focal point of last month’s downgrade — saw some downward revision. Revisions were particularly deep in business investment — to -5.9% from -4.1%, worth two tenths of the revision — and in inventories (also worth nearly two tenths).

What about 2010? The charts above paint a W shape hitting next Fall. The consensus projection is for 2.5% overall growth; a good example of it is here. The consensus says the recession is behind us, as is the meltdown of financial markets, but serious headwinds limit growth. This growth is below the level needed to turn unemployment around, since we need around 3% to employ new workers (net of retirees) to the workforce. This growth is also much less than typical coming out of a recession. The Reagan bounce out of the Carter recession had 6% growth, and the FDR bounce out of the Hoover depression had double-digit growth.

This consensus growth also implicitly assumes a W shape within it. Here is a set of scenarios by Dr Conerly shows his prediction quarter by quarter, and two scenarios of how inventories can ratchet the numbers: the red line is rapid inventory rebalancing, followed by a drop that turns GDP negative, and the green line is more modest swings in inventory:

He sees 2010 peaking in the first half and then softening. The 2.5% consensus scenario contains within it the same assumption: more rapid recovery in the first two quarters, and then a drop in the end of the year that makes the overall rate a modest 2.5%. We may not go negative, but seem at the moment to be destined to go to near flat GDP in the second half of 2010. The projections for a rebound in 2011 are so speculative they should be ignored.

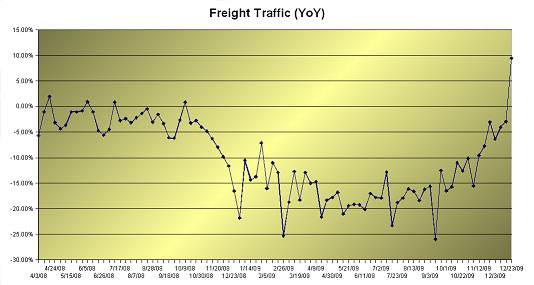

Whether it actually goes negative depends on the private economy. Some early indicators in freight give concern. Think of them as the fundamental underpinnings of the Transports in Dow theory: if the Industrials are up but Transports soften, it indicates excess inventory and a drop to come. We saw FedEx do well recently, probably driven by bouyant online sales that should drop after the holiday sales season. We still have “ghost ships” globally, idled oil tankers with floating inventory, and empty container ships. The RR bought by Buffett, Burlington Northern, has estimated tepid results next year. Its shipments are down 14% in Q4, and other RRs have also announced drops, such as Union Pacific at -7%. While RR traffic blipped up just last week, it is still down vs 2007, and this the first and only week in 2009 above negative YoY growth:

The next big concern is Obama suddenly becoming concerned over the deficit. Well, it is an election year in 2010 and the Demo’s are facing a debacle. He is expected to raise taxes and cut some spending, but balance it with more bailouts and stimulii. Ed Harrison asks “how [can] the Administration believe it can cut the deficit and add stimulus?” He answers, by raising taxes and by continuing the “bailout culture” of keeping the private economy on the string of government handouts and regulations to direct activity in favored directions. Think of the just-passed Senate healthcare bill – it turns private insurance companies into regulated utilities, with their profits capped and their services determined by bureaucrats. So far around 46% of the US economy has been so captured by Obama’s policies (banking, autos, mortgages, and now potentially healthcare). Ed Harrison concludes that Obama’s policies in 2010 are likely to drive the double-dip recession.

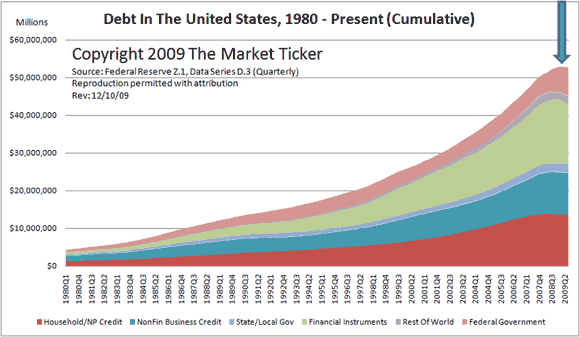

The final drag comes from the excessive debt in USD, which has only now begun to be written down. It first of all means further attempts to stimulate private borrowing are doomed. Defaults are increasing, and will soon accelerate, and bring with them deflation. This chart shows it has started, and has a long ways to go:

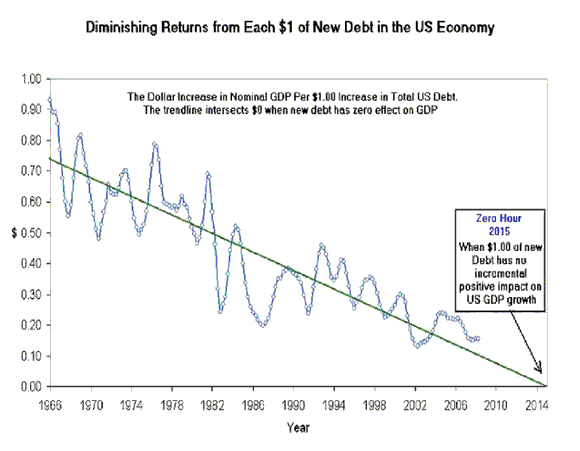

This excessive debt also emasculates the effects of Keynesian stimulus based on deficits. I will repeat a chart I have published before, on the marginal productivity of debt. It says we have borrowed too much (private and public) and need to write down a lot of debt to fix the economy. Every additional $ borrowed contributes less and less to GDP, and soon we will hit a point where every $ of new debt destroys GDP. That is the point of no return, since if the increase in debt is not stopped, we would be unable to earn enough from our economy to pay it off. Japan may be at that point right now, and many pundits have noted how we are following the Japanese path of the ’90s. They already are heading into their double-dip recession.

If something cannot happen, it won’t, so as we get close to that point everything will begin to go nonlinear. Fortunately we still have a few years to get serious about this problem instead of continuing to pour Stimulus and Liquidity into the economy, as Krugman keeps imploring us to do.

An example of the alternative is this Pro-Free-Market Program for Economic Recovery from the Austrians, who see the primary problem is the terrible difficulty for businesses to get capital today given the problems with the banking sector. Until that is fixed, the economy remains on life support, and the longer it continues, the longer the private sector stays stuck. Ironically, Bernanke’s great flood of liquidity is not going where it is needed, to businesses for working capital and growth. Fixing that requires a whole different approach than government programs and the bailout culture, and has three planks:

1. Require 100% reserves against demand deposits (checking accounts) which removes the need for an FDIC and restores integrity to banks that businesses rely on to hold their working capital. This does not restrict growth capital since longer-term deposits (eg. CDs) can be lent out at multiples of reserves. This does force banks to properly recapitalize, giving them the base to lend again.

2. Return to a global currency, probably based on gold, to remove the discretion of the reserve currency central bank (ie. the Fed) to debase the currency and drive inflation to serve domestic policies and politics.

3. Allow wages and prices to fall to clear the markets. One of the lessons of the Great Depression was that extensive wage and price controls created the high unemployment, and kept it high. Wages are held up today with a web of laws and actions, such as bailing out the auto unions in the guise of bailing out GM.

Sadly, such an approach is so outside the mainstream of thinking that we probably have to go through the Day of Reckoning of too much debt first, before we take a different path. Rather than war bailing us out of the bad policies of FDR and Hoover, we will need this debt debacle to bail us out of the equally bad policies of Bush and Obama.

There are glimmers of hope, however, as if various points of leadership are slowly rousing themselves out of a slumber. Barron’s ran a piece on the Fed stopping its easy-money madness. They correctly identify the cause of the current crisis as excessive credit driven by the Fed, not run-amok capitalism or evil bankers. They also establish that Krugman’s call for the Fed to reflate with even more liquidity is as wrong-headed as his prior calls for massive Stimulus:

When the Fed tries to induce business activity in this manner, it never lasts. This is because the central bank always has to cut off the flow of easy money, in fear of causing further damage in the form of rising consumer prices. When the Fed removes this artificial stimulus, business activity dependent on it grinds to a halt, asset prices plunge, and recession sets in. In some ways, the process is analogous to a doctor administering adrenalin to a patient. Remove the stimulus and the patient collapses.

The authors conclude that “lurching from crisis to crisis in a boom-bust fashion is unacceptable and unnecessary.” They recommend plank 2 above, removing the our currency from the discretionary vissitudes of politicians and the Fed, and backing it with something else, like gold.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

How does it feel to be insane?