For several months, I have been telling stories that decompose US economic activity into what I think of as cyclical and structural dynamics. I believe the distinction is very important to firms, markets, and policymakers who need to be aware when one dynamic is clouding their view of the other.

For several months, I have been telling stories that decompose US economic activity into what I think of as cyclical and structural dynamics. I believe the distinction is very important to firms, markets, and policymakers who need to be aware when one dynamic is clouding their view of the other.

The cyclical dynamics, in my opinion, are the most spectacular, the most visible. The real cyclical fireworks began in the second half of 2009, as the energy price shock decimated household budgets, quickly followed by a financial shock that triggered an additional pullback in demand. Firms unexpectedly found they had far too much excess capacity in this environment, and began the process of “rightsizing.” Lob losses mounted even as falling energy costs and lower interest rates for those not credit constrained began to put a floor under spending.

Eventually, firms would realign capacity with the new level of demand, and job losses would taper off. That would mark the early stages of the cyclical bottom, the point at which growths returns. The initial growth spurt could be very rapid, as firms restock inventory and pent-up demand comes into play. The additional of government stimulus will add additional fuel to the fire.

Once the early stages of recovery are complete, the story shifts from cyclical to structural. The boost from inventory correction, pent-up demand, and government stimulus fade, and the underlying growth rate, the fundamental rates of activity, becomes evident. Now your expectations about the nation’s economic direction depend on the weight you place on the structural factors. If you place nearly zero weight on those factors, then growth remains fairly high as the economy rapidly returns to potential. In effect, cyclical dynamics dominate your story; the Fed is simply flipping a switch that shifts the economy from high to low states and back again, a traditional post-WWII business cycle. If you place heavy weight on structural stories, you talk about the inability to revert to past patterns of consumer spending growth due to excessive household debt, a reversion to global imbalances that supports outsized import growth, lack of an asset bubble to compensate for these structural problems, etc. With these stories in your toolkit, you expect a low underlying growth rate – barely at potential growth – in which case the gap between actual and potential output remains distressingly high for possibly years to come.

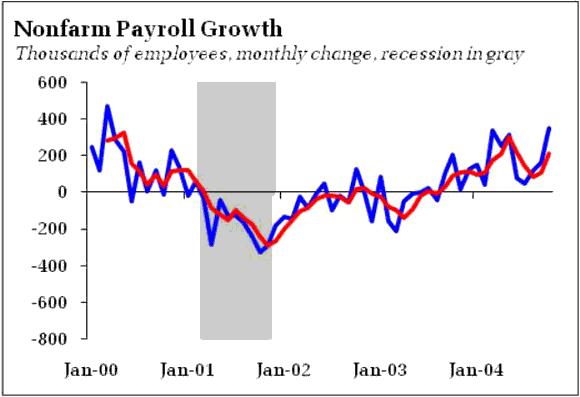

I tend to view incoming data through both cyclical and structural lenses. The employment report is a prime example. Clearly, the steady improvement in the rate of deterioration of nonfarm payrolls since the spring follows the cyclical pattern as firms stop chasing demand down and thus stabilize their workforces. Moreover, recent increases in temporary help hiring also points to firming labor demand in the months ahead. It would seem that stronger growth does in fact have the desired impact on labor markets, and that fiscal stimulus helped accelerate recovery in the labor markets.

At the same time, though, one has to wonder what happens as the stimulus begins to fade? Will there be sufficient demand from other sectors to compensate for fiscal and monetary withdrawal? It is worth recalling the patterns of labor market dynamics as we exited from the 2001:

After the post-recession boost – inventory correction, pent-up demand, etc. – labor markets quickly returned to a period of stagnation that lasted until the housing bubble began to take hold. What in the next two years can we expect to take the place of that bubble? Furthermore, if you are worried about a relapse in the pace of growth, the ISM reports last week were not exactly comforting. Both revealed an overall slowing of activity, and employment signals were not exactly consistent with a strong rebound in hiring anytime soon. For that matter, the ADP report, while not one of my favorites to begin with, came in far below the actual NFP numbers, suggesting that maybe this employment report was a little stronger than the underlying trend.

Also worth noting is the dismal reports on retail sales that appear to have largely slipped below the radar last week. From the Wall Street Journal:

Many retailers are likely to start offering broader discounts and promotions before the end of the holiday shopping season in response to generally lackluster sales the stores reported for November, retailing experts said Thursday.

Overall, sales at stores open at least a year edged up less than 1% last month compared with a year earlier, according to data collected by Retail Metrics Inc., which catalogs sales at 30 retail chains. Wall Street analysts had been expecting a 2.2% increase.

Consumers did lay siege on retailers during the post-Thanksgiving shopping weekend, but kept to strict budgets, seeking out deals but shying away from anything not marked down. Households in general appear to be adopting my wife’s mantra: “Fifty percent off just isn’t good enough anymore.” Now retailers are faced with the prospect they thought leaner inventories could help them avoid, ongoing markdowns throughout the holiday seasons, albeit not as bad as last year.

The bottom line is that what you need to take away from the current economic environment varies widely. Business in general should anticipate growth – growth that may be lackluster, vulnerable to policy withdrawal, and less dependent on consumer spending, but growth nonetheless. And any growth will force firms to reevaluate their hiring, sales expectations, supplier efficiency, etc. Don’t be surprised if anecdotal stories of firms unable to find qualified workers start to emerge. The skills of those who lost jobs may simply be inconsistent with the needs of employers. In short, be prepared for scenarios that don’t result in the end of the world as we know it, but still a different world with different patterns of activity.

This message to firms, however, is not nearly the whole story as far as policy is concerned. Policymakers need to be much more focused on the gap in current activity relative to potential than the rate of activity itself. Indeed, for all the excitement over the end of the recession, the 2.8% growth rate of 3Q09 is in the range of potential growth. It won’t close the output gap, and it won’t generate enough job growth to do much more than keep unemployment from rising further. Can the 2.8% number be maintain as fiscal stimulus fades and consumer spending ekes out historically meager gains? That should be question number one for policymakers. Number two should be: What more can we do to ensure that we push well ahead of 2.8%?

And question number two should be this: Why did the US economy yield such horrible employment performance this decade? The fact that we have just experienced a lost decade for jobs should be on policymaker’s tongue. But it is not, I suspect because in many ways the lost decade was hidden by the spectacular rise and fall of housing, leaving few to reflect on the meaning of an economy which would have been in a decade-long jobless recovery without an asset bubble in the middle.

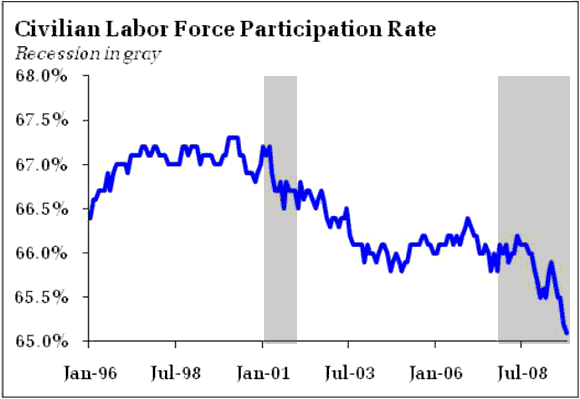

Moreover, policymakers have been lulled into a certain complacency on the job picture because on the exodus from the labor markets, with civilian labor force participation peaking ahead of the last recession, thus keeping a “lid” on unemployment rates:

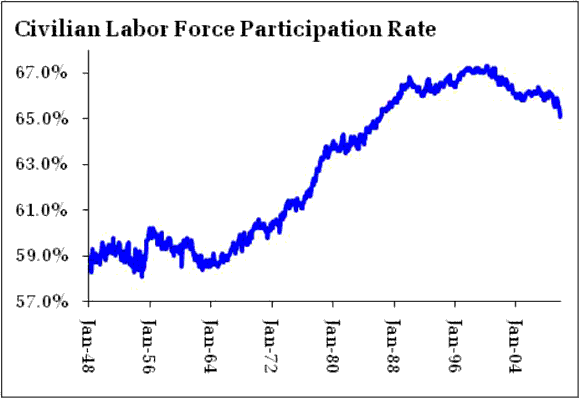

And a longer view:

The beginning of this decade marked the end of a 35 year trend of increasing labor force participation. Is is a coincidence that this trend ended as the lost decade for US jobs began? Are these trends reinforcing each other? How so, and what does it imply about the prospects for jobs for the next decade?

But these, like the problematic imbalance between China and the US (if the imbalance re-exerts itself in the months ahead, how many of the recently lost US manufacturing jobs are likely to be recovered?), are very big questions. Questions policymakers are not likely to have much time for as they are lulled into a false sense of security by positive growth and improving nonfarm payrolls numbers – especially if unemployment stops rising.

The Administration has already made clear its concerns about the deficit. On the monetary front, those who worry about the yawning gap in potential output believe that more easing is desperately needed. The employment report, however, will tend to push policymakers in the other direction, a greater willingness to let the Fed’s balance sheet contract, perhaps even deliberately rather than via the natural expiration of now unneeded financial market supports. To be sure, a push to raise the Fed Funds rate is premature; I believe the Fed intends to keep rates at rock bottom levels in the face of high unemployment. But this is not the relevant policy issue. The relevant issue is whether or not Fed policymakers are prepared to do more to close the output gap. Already, only St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard looked open to such policy. But I suspect his position will only get more lonely as job growth, even lackluster job growth, builds. Indeed, the policy risk is a more rapid reversal of the Fed’s balance sheet expansion as hawks like Richmond Federal Reserve President Jeffery Lacker – already concerned that the Fed need to prove its independence – increasing argue with a more rapid exit from the emergency expansion even as while the main policy rate holds at zero.

Bottom Line: Cyclical and structural forces are at play. But be wary about confusing the two; I fear this to be a particular problem for policymakers. Economic growth is likely to lead to complacency, but such complacency would be ill-advised when the decade’s record on nonfarm payrolls leaves the job-generating capacity of the US economy in doubt.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply