Paul Krugman has chimed in on my figure showing the collapse in nominal spending. He, however, is less enthusiastic about its implications:

[The figure is] certainly suggestive. But I disagree with the interpretation that this shows that the current slump is mainly about insufficiently expansionary monetary policy……

Focusing on nominal spending makes you think that low nominal spending is the problem, a problem with a monetary solution; but actually it’s the symptom, and monetary policy doesn’t matter (unless it can affect expected future inflation, but that’s another story).

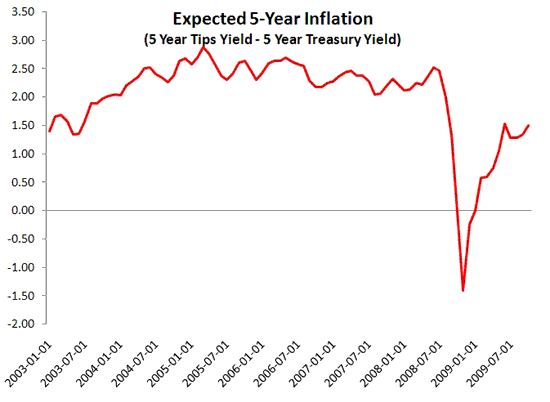

Note that the part about changing expectations of future inflation in parentheses is actually an admission that monetary policy can do something about the current slump. Krugman, however, does not explore this point anywhere else in his post. That is unfortunate because it is the very argument advocates like Scott Sumner have been making in their case that monetary policy could have done more to prevent the nominal spending crash of 2008-2009. One way to think about this is to imagine what would have happened had the Fed set an explicit inflation target of say 3% in mid-2008 and promised it would do whatever was needed to keep actual inflation there. If such a policy had been adopted it is unlikely inflation expectations would have collapsed liked they did in late 2008, early 2009 as seen in the figure below:

And if inflationary expectations had not collapse then current nominal spending would have been far more stable. This is because if folks think that inflation will be permanently higher going forward they are more likely to spend their money today. That is, money demand will fall and velocity will pick up.

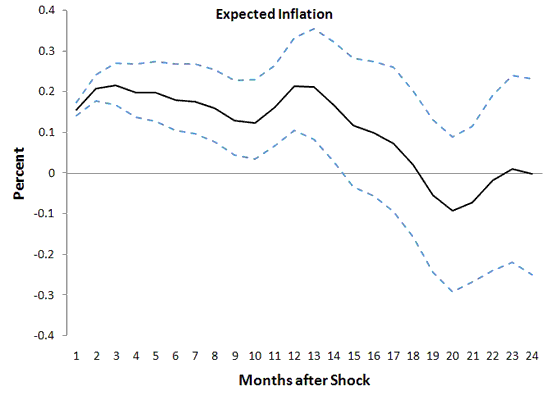

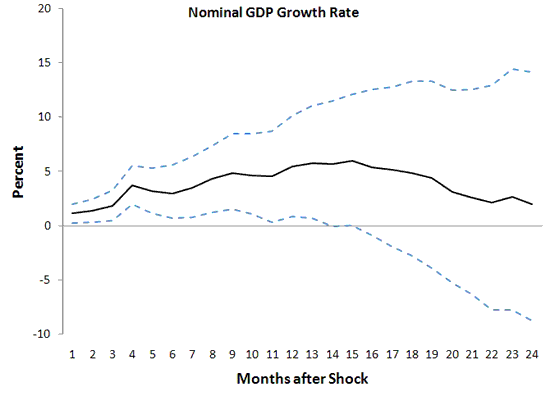

This is a point I empirically tested in a recent post. There I took the monthly expected inflation series implied by the difference between the nominal 10-year Treasury yield and the 10-year TIPs yield and put it in a vector autoregression (VAR) along with the monthly GDP series from macroeconomic advisers. Nominal GDP was turned into an annualized monthly growth rate and the data used runs from 1999:1 through 2007:9. More data would have been helpful, but TIPs only start in the late 1990s.* The two figures below show what the typical responses of expected inflation and nominal GDP to the typical sudden change or shock to expected inflation over the sample. The solid line shows the point estimate while the dashed lines show two standard deviations around the point estimate. Upon impact, the shock causes expected inflation to jump 16 basis points and occurs as the level of nominal GDP increases by 1.16 percent. In other words, a sudden positive change in expected inflation is associated with an increase in current nominal spending. Both effects persist but eventually become insignificant about 14-15 months later.

So contrary to Krugman’s claim, there is reason to believe the Fed could have prevented the great nominal spending crash of 2008-2009. The real question for me is why did the Fed allow inflationary expectations to fall so dramatically in late 2008, early 2009. My guess is they simply dropped the ball or there was too much pressure from inflationary hawks.

Update I: The Economist blog Free Exchange responds to Krugman’s post by arguing that monetary policy is not out of gas.

Update II: Scott Sumner also shoots down Krugman’s nominal nonsense.

*(Technical note: both series were in rates so no unit root problems, 13 lags were used to eliminate serial correlation, and corporate bond spreads were included as a control variable for the financial crisis).

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply