The 2008 financial crisis is sometimes characterised as one where financial difficulties in the US spread to the rest of the world. But is there clear evidence of such international contagion? This column reports research indicating that neither financial nor trade linkages to the US help explain the cross-country incidence of the crisis. If anything, countries more exposed to the US seem to have fared better.

The roots of the 2008 global financial crisis surely lie in the US real estate bubble, at least in part. After the US real estate market peaked in 2006, mortgage foreclosures began to rise, especially for subprime borrowers. Accordingly, the value of these mortgages – often pooled together and sold off as pools of securitised assets – began to fall.

Almost immediately, problems began to show up in US financial markets. During the spring and early summer of 2007, US real estate lenders began to experience troubles, and a number went bankrupt. Eventually credit markets deteriorated to the point in early August where central banks around the world – including the Federal Reserve but also central banks in Australia, Canada, Europe, Japan, Singapore, Switzerland, and the UK – were forced to pump liquidity into the markets. Succinctly, it seemed like the US subprime mortgage meltdown had metastasised into a global financial panic (see Reisen 2008 and Reinhart, 2008).

The events of September 2008 seem only to strengthen the case for contagion. The US investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy on 14 September, leading to a week of chaos on US financial markets. The financial carnage spread overseas immediately; Iceland, Ireland, the Baltics, and the UK (among many others) all experienced financial panic and declining markets.

The case for contagion seems superficially clear. In this column, we discuss our recent research that probes more deeply into the 2008 crisis. In particular, we ask if countries that were more heavily exposed to toxic US assets suffered deeper losses during the crisis of 2008.

Surprisingly, our answer is negative – countries that had disproportionately high amounts of trade with the US in either financial or real markets did not experience more intense crises. If anything, countries more heavily exposed to the US seemed to fare better than others. And our results are robust; we examine over 40 different linkages between countries, in both trade and capital. This negative finding makes us sceptical of the ability of “early warning systems” – such as the one discussed in the de Larosiere Report (2009) – to successfully predict the incidence of future crises across both countries and time.

Measuring crises and international linkages

To test whether crises spread contagiously between countries, one needs measures of both crises and contagion. In a recent paper (Rose and Spiegel, 2009b), we provide both. Our model of the crisis is straightforward. We combine 2008 changes in real GDP, the stock market, country credit ratings, and the exchange rate into a single measure of crisis incidence. This delivers an estimate of the intensity with which the 2008 crisis struck each country. We use a “MIMIC” (Multiple Indicator Multiple Cause) model (Goldberger, 1972) to link national causes and consequences of the crisis, as well as estimate the incidence and severity of the 2008 crisis. The MIMIC specification explicitly acknowledges that the severity of a crisis is a continuous, rather than a discrete, phenomenon that can only be observed with error. The model also allows us to control for national causes of the crisis; we use those identified by Rose and Spiegel (2009a).

To measure contagion, one needs a linkage between the epicentre of the crisis (the US) and other countries. We experiment with a variety of different approaches. A country’s trade exposure to the US is measured as bilateral trade between the country and the US, expressed as a proportion of the country’s total trade. Similarly, US financial exposure is measured as total holdings of US assets held by a particular country as a fraction of the county’s total external assets. We concentrate on the US, the likely epicentre of the origins of the crisis. However, we also consider exposure to other nations, such as Germany, the UK, Spain, Korea, and Japan. We also consider a number of measures of both trade and financial assets.

Evidence of international linkages

We begin by estimating a MIMIC model, using a country’s size, income, and 2003-6 stock market rise as causes of the 2008 crisis. We choose these variables based on our earlier work, summarised in Rose and Spiegel (2009a).

We then add each of the potential financial linkages to our default MIMIC model one by one (consistently retaining size, income and the 2003-6 stock market rise as causes). Surprisingly, we obtain a positive and statistically significantly coefficient estimate for exposure to US assets. That is, countries with more exposure to US financial assets seem to have experienced less intense crises, rather than more. Moreover, this result seems to be insensitive to the exact econometric specification of the statistical model.

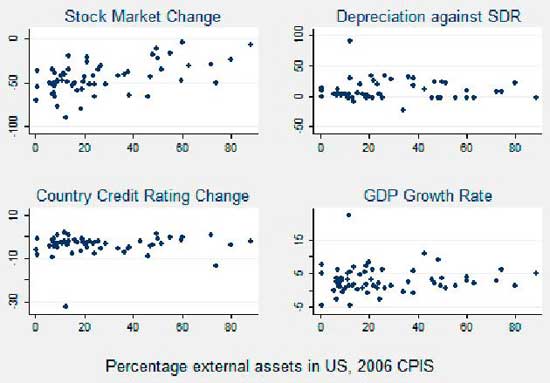

The result that countries with greater exposure to US assets experienced less severe crises is surprising, but it seems to be observable in the raw data. Figure 1 provides simple scatter-plots of our four manifestations of the crisis graphed against the share of external assets held in the US. There certainly is no apparent adverse impact of US exposure. Indeed, countries that had larger shares of their 2006 foreign wealth in America seem systematically to have experienced smaller stock market declines in 2008.

Figure 1. 2008 crisis manifestations against American assets

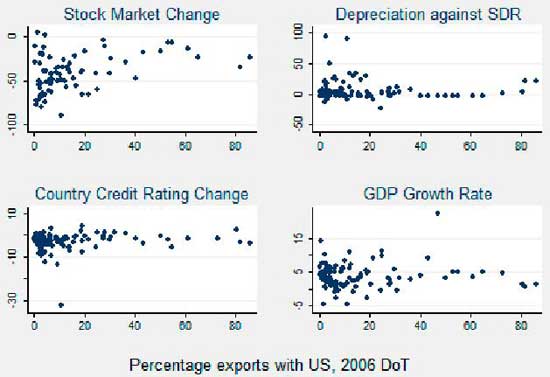

We next search for evidence of real channels for exposure to contagion, measured through bilateral trade exposure. First, concentrating on exports, we again obtain surprising results; greater export dependence on the US leads systematically to less intense financial disruptions. Figure 2 provides the relevant graphical evidence, scattering the four crisis manifestations against export dependence on America. This relationship does not characterise other potential epicentres of the crisis; there is little systematic strong evidence that export dependence matters. We obtain similar results when we examine total trade (rather than just exports) or include trade and financial linkages simultaneously.

Figure 2. 2008 crisis manifestations against American exports

Conclusion

Our work has a severely limited scope. Even if we had found that exposure to either real or financial contagion played an observable role in the determination of relative performance in the current crisis, our results would not indicate that early warning models of the relative incidence of future crises will perform well. Our analysis worked with the benefit of hindsight; we knew that there was a crisis in 2008, and that its epicentre was the US. Such knowledge would not be available to real-time forecasters.

However, even with the benefit of hindsight, we did not find evidence that the 2008 financial crisis spread contagiously from the US to other countries, even though we examined a number of financial and real channels that might make other countries vulnerable to an US downturn. Indeed, countries that were more exposed to the US seem – if anything – to have experienced smaller crises, holding other factors constant.

Overall, we find remarkably little evidence that the cross-country intensity of the 2008 crisis can be modelled using quantitative techniques. This negative finding in the cross-section makes us sceptical of the ability of “early warning systems” to successfully predict the incidence of future crises across both countries and time.

References

•Goldberger, Arthur S. (1972) “Structural Equation Methods in the Social Sciences” Econometrica, 40, 979-1001.

•de Larosière Group, 2009, “Report of the High Level Group on Supervision.”

•Rose, Andrew K. and Mark M. Spiegel, (2009a), “Cross-Country Causes and Consequences of the 2008 Crisis: Early Warning,” CEPR Discussion Paper 7354.

•Rose, Andrew K. and Mark. M. Spiegel (2009b) “Cross-Country Causes and Consequences of the 2008 Crisis: International Linkages and American Exposure,” CEPR Discussion Paper 7476.

•Reinhart, Carmen (2008), “Reflections on the International Dimensions and Policy Lessons of the US Subprime Crisis”, VoxEU.org, 15 March.

•Reisen, Helmut (2008), “The fallout from the global credit crisis: Contagion – emerging markets under stress”, VoxEU.org, 6 December.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply