A missive from a former colleague prompted me to reconsider the Fed’s behavior in light of their most recent forecast and the evolution of economic data. That in turn started to shed light on some little pieces of information sitting on my computer that I knew were important, but just couldn’t quite see how they fit. And has left me somewhat concerned that the Fed may be more likely than I believed to stifle the pace of the recovery by, at a minimum, halting the growth of policy accommodation.

The Fed gave and took at the September FOMC meeting. Policymakers reiterated support for their near zero rate policy, while offering a slightly hawkish nuance that was noted by Jon Hilsenrath at the Wall Street Journal:

Today’s Federal Open Market Committee statement included a nuanced tip of the hat to hawks on the central bank’s policy making committee who think the Fed is putting too much weight on the argument that the economy’s substantial slack will drive down inflation.

Slack is the economy’s productive capacity that doesn’t get utilized — unemployed workers, empty hotel rooms, unsold homes, idle factory floors, etc. When there’s a lot of slack, it puts downward pressure on prices in the short-run. It’s one very important reason why the Fed has felt comfortable assuring markets that it is likely to keep interest rates exceptionally low for a long time. Because slack is likely to keep inflation low, the Fed will keep rates low.

But Fed officials have been engaged in an intense debate in recent months about how much slack matters. Some hawks believe other factors are more important ingredients in near-term inflation. One of those other factors is inflation expectations — if investors, businessmen and consumers expect more inflation, they could cause it by demanding higher prices and wages in anticipation. The Fed indirectly acknowledged this argument in the September statement: “With substantial resource slack likely to continue to dampen cost pressures and with longer-term inflation expectations stable, the Committee expects that inflation will remain subdued for some time.”

In previous recent statements, it hasn’t mentioned inflation expectations. It focused mostly on slack. Here’s how the Fed put it in August: “Substantial resource slack is likely to dampen cost pressures, and the Committee expects that inflation will remain subdued for some time.”

The practical implication of this little wording change? Keep an eye on measures of inflation expectations, such as inflation-protected Treasury bonds and University of Michigan surveys of consumers. They have been stable. But if they start rising, the Fed’s inflation view could change and tilt it toward a more hawkish stance.

The shift in wording, then, appears to be the result of some more hawkish FOMC members, illuminating the smidgen of truth behind a rumor that was circulating earlier this month. From Across the Curve:

I was not planted here at my work station yesterday but roaming through the myriad of emails I receive it seems that one of the reasons for the weakness yesterday was a report by an advisory firm, Smick Medley, that the Federal Reserve at its upcoming meeting would comment on and discus raising rates sooner rather than later.

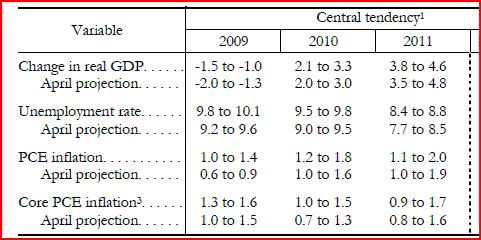

Given the FOMC’s own forecast, any consideration of tightening seems silly:

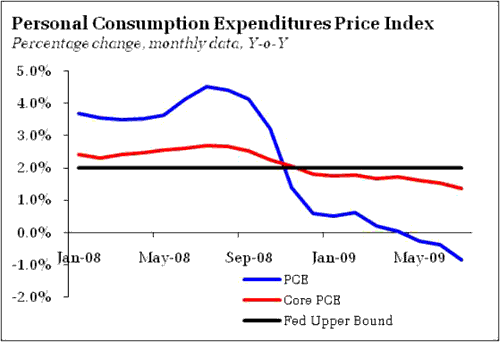

While the Fed may find it necessary to raise the estimate of GDP growth for this year on the back of a relatively sharp inventory correction, unemployment is almost certain to exceed the range for this year, and even if it didn’t, it remains unacceptably high through 2011. Moreover, the downward pressure on pricing has increased in recent months, bringing the core-PCE forecasts into question:

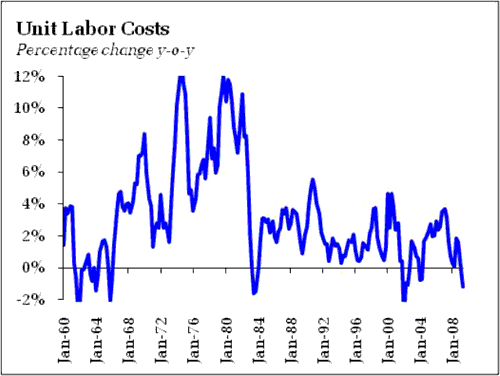

On top of this, the concern of some hawks that inflation expectations will suddenly trigger a wage price spiral seems simply silly unless one can explain how, given current institutional arrangements in the US, price increase will translate into wage increases. Indeed, unit labor costs are giving you the exact opposite story:

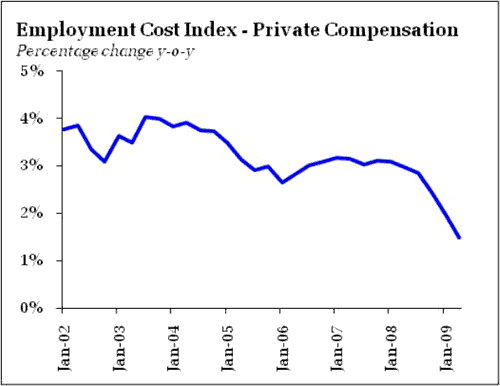

And employment compensation for the private sector is likewise trending down:

Sure, one could turn to the commodity markets for inflation signals, but I think the critical price there is oil, which is finding the $72 mark extremely challenging to break through. That may have something to do with reports that quantity supplied to running well ahead of quantity demanded:

Crude oil declined for a second day in New York after a U.S. government report showed a larger-than- expected increase in fuel stockpiles in the world’s largest energy-consuming nation.

Gasoline stockpiles in the U.S. surged 5.4 million barrels last week, the Energy Department said. That’s more than the 500,000-barrel increase forecast in a Bloomberg News survey of analysts. Diesel and heating oil inventories jumped 2.9 million barrels, double what was expected. Crude oil supplies climbed 2.86 million barrels last week.

“The market has a glut of crude oil and refined products right now,” Victor Shum, a senior principal at consultants Purvin & Gertz Inc. in Singapore, said in a Bloomberg Television interview. “If we get a big correction in equities, the loss of optimism in that demand recovery will continue to drive down prices.”

And even if oil broke through the $72 mark, if $150 oil couldn’t trigger a wage-price spiral, what is $80 oil going to do? The Fed’s seeming eagerness halt monetary accommodation also runs in contrast to forecasts that they really need to be doing much, much more to support growth. From Goldman Sachs (no link):

In recent months, we have argued that the zero lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates represents a meaningful constraint on monetary policy in particular and economic policy in general. Specifically, combining a variant of the Taylor Rule for monetary policy with our forecast for growth and inflation, we have long concluded that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would want to push its target for the federal funds rate significantly below zero – to levels of -6% or lower – if it had that option.

The -6% number suggests a much, much more aggressive expansion of the balance sheet, while the Fed in contrast is willing to let the current programs play themselves out over the course of the next six months.

So, given the unemployment outlook is sad, wage growth continues to deteriorate, core inflation is falling, and we seem to lack an institutional arrangement to force higher prices, should they even emerge, into higher wages, what is the Fed thinking? Should they really be worried about winding down programs? Are they really confident enough that an inventory correction that will undoubtedly spike GDP numbers will also translate into sustainable growth? Even knowing full while that after the last recession, the US economy languished despite the inventory correction, only to be revived on the back of the housing bubble? In effect, the Fed looks to be putting much weight on the cyclical story playing out, while ignoring the structural story of the necessity of asset bubbles to fuel growth. Pondering this, a little noticed Bloomberg report jumped to mind:

Federal Reserve policy makers are concerned about making “a colossal policy error” leading to higher inflation if they don’t withdraw extraordinary monetary stimulus soon enough, said Laurence Meyer, vice chairman of Macroeconomic Advisers LLC and a former Fed governor.

“When you talk to committee members you see a little bit more angst than you’d expect,” Meyer said in an interview yesterday at the Kansas City Fed’s monetary policy conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “In public they say they’re confident they’ll get it right, they’re confident they have the tools to get it right. But when you talk to them in private there’s some concern there.”

So, added to the Medley rumor, the pieces start to fall together. Internally, perhaps a wide range of FOMC members believe, in their hearts if not in the data, that they have gone so far that the balance of risks have shifted toward inflation. But this is troubling; the basis for the inflation story falls entirely on the Fed’s expansion of its balance sheet. Just a meager $1.3 trillion expansion give or take in the wake of an over $11 trillion decline in household wealth? And the bulk of that expansion is sitting in excess bank reserves? Not really much of an inflation story. But why else are they so eager to withdraw? Just to prove to critics they can? With much fanfare, from Bloomberg today:

The Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury said they’re scaling back emergency programs aimed at combating the financial crisis, reducing support for firms that now have an easier time getting funding.

The central bank today said it will further shrink auctions of cash loans to banks and Treasury securities to bond dealers, reducing the combined initiatives to $100 billion by January from $450 billion. The Treasury has “begun the process of exiting from some emergency programs,” the chief of the government’s $700 billion financial-rescue fund said separately.

Bottom Line: The Fed is moving toward the exit as they look toward the conclusion of their securities purchases programs. But it is not clear that such a move is justified by their own forecasts or the inflation/wage/employment data. There may be an internal fear they have gone too far, a fear that the hawks can exploit. To be sure, I see no reason to expect the Fed will raise rates for a long time. And the Fed maintains it policy flexibility, claiming to be ready to revive asset purchases should economic or financial conditions justify. But I now suspect the bar for renewed expansion of Fed accommodation may be much higher than I had anticipated. And that the dominant push for expansion would have to come from financial market conditions, while they would be willing to tolerate persistently high unemployment rates so long as U. Michigan inflation expectations say elevated, regardless of the actual inflation data.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply