From Reuters:

Russia is at risk of recession as investors pull money out of the country, with growth likely to evaporate if capital outflows reach $100 billion, the head of its largest bank, state-owned Sberbank, said on Monday.

Capital has fled Russia, with stocks and the rouble sliding following Moscow’s seizure of Crimea from Ukraine and western sanctions against Russian individuals. Analysts at Goldman Sachs recently predicted capital outflows for this year could reach $130 billion, or double 2013 levels.

And from K. Hille and R. McGregor in the FT, assessments from Russian government officials:

The Russian government is braced for the country’s capital outflows to soar to $70bn in the first three months of the year as investors seek cover from the fallout of President Vladimir Putin’s Ukrainian land grab.

…That would exceed the $63bn that flowed out of the country in the whole of last year and is higher than the $50bn figure mooted by Mr Putin’s economic adviser Alexei Kudrin 10 days ago.

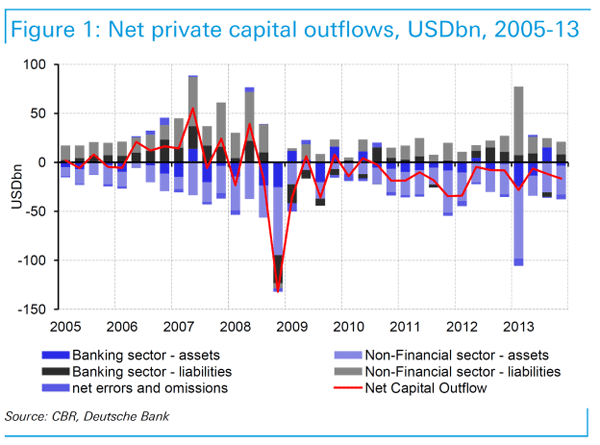

It appears that Russia is more vulnerable to sanctions, and the threat of sanctions, than some observers believed (see discussion here). Figure 1 places in context the developments in the external balances, including net capital inflows, through 2013.

Figure 1 from Y. Lissovolik, A. Zaigrin, “Russia: macro implications of increased geopolitical risk,” Emerging Markets Monthly (Deutsche Bank, 13 March 2014) [not online].

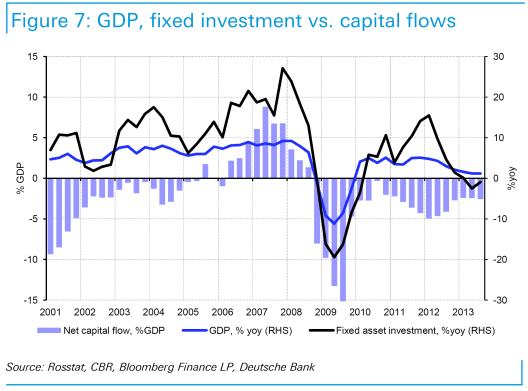

The figures in the graph are not annualized, so net outflows of $100 billion in Q1 would dwarf those recorded in earlier quarters. There is a strong correlation between capital inflows and fixed investment (and the investment contribution to GDP growth in 2013Q4 was already zero). Figure 7 illustrates this correlation.

Figure 7 from Y. Lissovolik, A. Zaigrin, “Russia: macro implications of increased geopolitical risk,” Emerging Markets Monthly (Deutsche Bank, 13 March 2014) [not online].

From my own perspective, I was surprised that growth forecasts had not already been marked down to zero and below. After all, the policy rate has already been raised by 1.5 ppts to 7% as of the beginning of March. [1] A standard Mundell-Fleming analysis in the absence of balance-sheet/foreign exchange concerns suggests this measure is contractionary; with foreign currency denominated debt, the interest rate defense might make sense as the lesser of two evils, but doesn’t take away from the fact that raising the policy rate is contractionary. Admittedly, with y/y inflation at 6.2%, the increase makes real interest rates less negative, rather than more positive. In addition, with an underdeveloped and fragmented financial system, the link from the policy rate to lending rates is probably weak.

It’s of interest that these developments are occurring against a backdrop of already priced in monetary tightening in the United States. Should economic conditions induce a revision toward more rapid tightening, or general risk appetite decline, pressure on Russian external balances — and foreign exchange reserves — pressure on the Russian economy will only increase.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply