I think it is remarkable that, despite the growth the US has enjoyed since the 1960s, the poverty rate has barely changed. Writing for the Wall Street Journal last month under the title “How the War on Poverty Was Lost”, Robert Rector notes that: “Fifty years and $20 trillion later, LBJ’s goal to help the poor become self-supporting has failed.” He writes further:

On Jan. 8, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson used his State of the Union address to announce an ambitious government undertaking. “This administration today, here and now,” he thundered, “declares unconditional war on poverty in America.”

Fifty years later, we’re losing that war. Fifteen percent of Americans still live in poverty, according to the official census poverty report for 2012, unchanged since the mid-1960s. Liberals argue that we aren’t spending enough money on poverty-fighting programs, but that’s not the problem. In reality, we’re losing the war on poverty because we have forgotten the original goal, as LBJ stated it half a century ago: “to give our fellow citizens a fair chance to develop their own capacities.”

…LBJ promised that the war on poverty would be an “investment” that would “return its cost manifold to the entire economy.” But the country has invested $20.7 trillion in 2011 dollars over the past 50 years. What does America have to show for its investment? Apparently, almost nothing: The official poverty rate persists with little improvement.

My impression is that there are far more “poor” people today as a percentage of the population than there were in the 1960s, because lower middle-class and middle-class people have moved into the ranks of the poor. (Since 2007, the bottom 50% by wealth percentile lost more than 40% of their net worth and their debts are up 16%.) This may be a factor that explains the still muted consumer confidence at a time when stock investors’ sentiment is at its highest level since 1987.

In my opinion, the increase in poverty rests on four pillars: cultural and social factors, educational issues, excessive debt, and government handouts, which encourage people not to work. Other factors include: international competition, which keeps wages down; and monetary policies, which create bubbles and impoverish the majority.

As an example, social factors and government handouts led to a sharp increase in out-of-wedlock births. In the 1960s in the US, out-of-wedlock births comprised only 5.3% of total births; in 1980, 18.4%; and today, over 40%. Babies born out of wedlock are likely to have fewer educational opportunities than those raised in two-parent families.

This is one reason; educational standards have also slipped – certainly relative to the rest of the world – due to poor policies. Of course, by far the worst cause of rising poverty rates is monetary policies that have encouraged credit growth, enslaving poor people with debts and financing an increase in entitlement programs by the government.

According to Rector, “The federal government currently runs more than 80 means-tested welfare programs that provide cash, food, housing, medical care and targeted social services to poor and low-income Americans. Government spent $916 billion on these programs in 2012 alone, and roughly 100 million Americans received aid from at least one of them, at an average cost of $9,000 per recipient. (That figure doesn’t include Social Security or Medicare benefits.) Federal and state welfare spending, adjusted for inflation, is 16 times greater than it was in 1964. If converted to cash, current means tested spending is five times the amount needed to eliminate all official poverty in the U.S.”

It is no wonder, therefore, that with these generous social programs, largely financed now by the Fed, single women have been encouraged to have babies without the “inconvenience” of having a husband.

The problem, however, as I mentioned above, is that (again according to Rector) the Heritage Foundation has found in a study that “children raised in the growing number of single-parent homes are four times more likely to be living in poverty than children reared by married parents of the same education level. Children who grow up without a father in the home are also more likely to suffer from a broad array of social and behavioral problems. The consequences continue into adulthood: Children raised by single parents are three times more likely to end up in jail and 50% more likely to be poor as adults.”

Now, I realise that it would be unfair to place the entire blame on the Fed for the failure of entitlement programs. However, the Fed and other central banks around the world have been enablers of Big Government and poor economic policies. As John Taylor (a professor of economics at Stanford University, and one of the few economists who appears to be sane) opined in the Wall Street Journal about the various secular stagnation hypotheses:

In the current era, business firms have continued to be reluctant to invest and hire, and the ratio of investment to GDP is still below normal. That is most likely explained by policy uncertainty, increased regulation, including through the Dodd Frank and Affordable Care Act, about which there is plenty of evidence, especially in comparison with the secular stagnation hypothesis.

I suppose the emergence of the secular stagnation hypothesis shouldn’t be surprising. As long as there is a demand to pin the failure of bad government policies on the market system or exogenous factors, there will be a supply of theories. The danger is that this leads to more bad government policy [emphasis added]

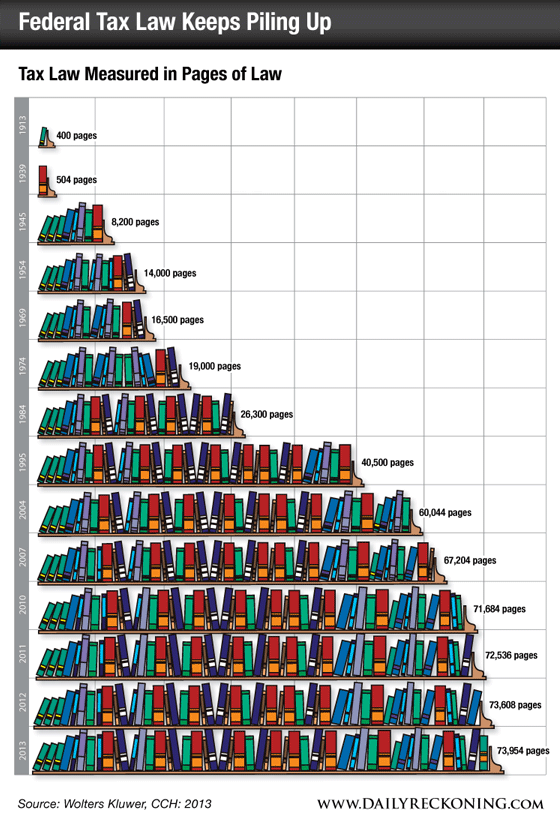

Concerning increased regulation it is clear that “Big Business” loves increased regulation. Take, as an example, the increasingly complex tax laws (click the chart to enlarge). Large corporations can hire an army of accountants, lawyers, tax consultants, and lobbyists in order to reduce their tax burden. But, what about the small business owner?

He is at the mercy of some tax collector who can waste his time endlessly with repeated audits. The same goes for other regulatory requirements, which lead to less competition and favour large business groups.

Many of my friends who own independent small money management firms are being forced to close down their businesses, merge, or sell to larger financial institutions because of increased regulation. The more regulation there is, the more likely it becomes an inhibiting factor for innovation.

Furthermore, I am certain that the secular stagnation hypothesis is another attempt by the government to justify more interventions with fiscal and monetary policies into the free market.

The question is, of course, who are the governments? Will Durant opined in The Age of Louis XIV that the “men who can manage men manage the men who can only manage things, and the men who can manage money manage all”. In Lessons of History, he wrote:

…the bankers, watching the trends in agriculture, industry, and trade, inviting and directing the flow of capital, putting our money doubly and trebly to work, controlling loans and interest and enterprise, running great risks to make great gains, rise to the top of the economic pyramid.

From the Medici of Florence and the Fuggers of Augsburg to the Rothschilds of Paris and London and the Morgans of New York, bankers have sat in councils of governments, financing wars and popes, and occasionally sparking a revolution. Perhaps it is one secret of their power that, having studied the fluctuations of prices, they know that history is inflationary, and that money is the last thing a wise man will hoard [emphasis added].

I suppose that one solace for poor people, in view of this rather sobering fact, may be these words of Frank McKinney Hubbard:

“It’s pretty hard to tell what does bring happiness; poverty and wealth have both failed.”

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply