Before the onset of the financial crisis, European households and non-financial firms were borrowing heavily in lower-yielding foreign currencies to finance their home mortgages or business investments, even though they did not necessarily have a steady income in the currency concerned. Five years after the financial crisis, banks still hold a substantial amount of foreign currency loans to unhedged borrowers on their balance sheets. This column quantifies the systemic risk that these foreign currency loans pose to the European banking sector.

Before the onset of the financial crisis, foreign currency loans to the non-banking sector in Europe became remarkably prevalent. In particular, households and non-financial firms were taking bank loans denominated in lower-yielding foreign currencies and investing in high-yielding domestic currencies (e.g., in the form of home mortgages or business investments), even though these agents did not necessarily have a steady income in the foreign currency concerned. Therefore these retail foreign currency loans were usually dubbed ‘small men’s carry trade’.

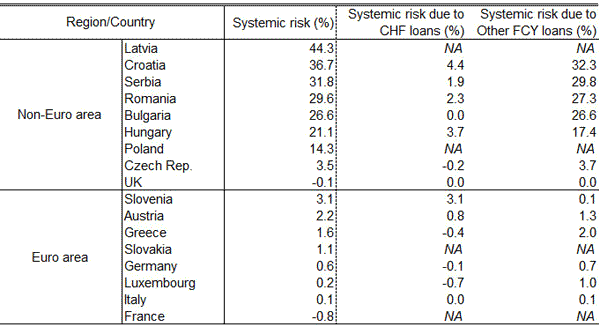

Since the crisis, the outstanding volumes of foreign currency loans to the non-banking sector have been slowly declining in some countries due to macro-prudential measures, deleveraging of banks, and the continued slowdown of European economies. Nevertheless a substantial fraction of households and firms still have foreign currency bank loans. Figure 1 shows that as of the second quarter of 2013 the majority of the outstanding loans to the non-banking sector in many non-Eurozone countries continue to be denominated in a foreign currency. For example, in Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Serbia, and Latvia, between 60% and 88% of the outstanding loans to the non-banking sector are denominated in a foreign currency.

Figure 1. Share of foreign currency loans as a percentage of total loans to the non-banking sector in Europe (2013:Q2)

(click to enlarge)

Source: CHF Lending Monitor

Notes: CHF, Swiss francs; FCY, foreign currency.

While foreign currency loans offer some advantages to borrowers – such as lower interest rates and longer maturities compared to domestic currency loans – they also carry a significant exchange rate risk. A sharp depreciation of the domestic currency can prevent unhedged borrowers from being able to service their foreign currency loans. As a result, these loans could create a substantial systemic risk to the European banking sector. Banks could fail jointly as a result of their exposure to unhedged households and non-financial firms which default on their loans when the domestic currency depreciates sharply.

Policymakers and international institutions have recognised the systemic risk that foreign currency loans pose to the European banking sector. For example, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), an independent institution monitoring financial stability within the EU, made an official recommendation on lending in foreign currency on November 22, 2011. In particular, the ESRB stated that “Excessive foreign currency lending may produce significant systemic risks for those member states and may create conditions for negative cross-border spillover effects.”

While policymakers in Europe repeatedly express their concern regarding the systemic risk created by foreign currency loans, there is a lack of literature on the exact measurement of this systemic risk. The ESRB, European central banks, and the European Bank for Restructuring and Development (EBRD) (among other policy institutions) are concerned about the prevalence of foreign currency loans to the non-banking sector, yet their policy discussions do not elaborate on the measurement of systemic risk.

An earlier paper by Ranciere, Tornell and Vamvakidis (2010) made a first attempt to quantify the currency mismatch on banks’ balance sheets due to foreign currency loans to the unhedged non-banking sector in Emerging Europe for 2004–2007. In a more recent paper, I take up this theme, build on their suggested method, and calculate accurate and detailed measures of systemic risk in 17 European countries for 2007–2011 using a novel dataset. I find that systemic risk is substantial in the non-Eurozone, while it is relatively low in the Eurozone.

Quantifying systemic risk

Systemic risk in the financial system is a multifaceted phenomenon. De Bandt and Hartmann (2000) and Georg (2011a,b) provide an in-depth discussion of systemic risk. One possible mechanism whereby systemic risk arises is through a simultaneous exposure of financial institutions to a ‘common market shock’. Since foreign currency loans are widespread on European banks’ balance sheets, a sharp exchange rate movement can trigger, for example, defaults of domestic households on their foreign currency mortgagees, which could lead to a simultaneous deterioration of the banks’ balance sheets. The approach to measure systemic risk in my recent paper adheres to this ‘common market shock’ mechanism, and quantifies the systemic risk as the net unhedged foreign currency liabilities of the banking sector as a percentage of their total assets. In other words, it evaluates the impact of a joint failure of unhedged borrowers to service their foreign currency loans on banks’ balance sheets in aggregate.

Data

All data are from the CHF Lending Monitor, which is an ongoing Swiss National Bank (SNB) project to understand the scope of Swiss franc (CHF) denominated bank lending in Europe. Nineteen European central banks have been sharing their aggregate banking sector statistics with the SNB on a quarterly basis since 2009. The data are confidential and have not been published.

Findings

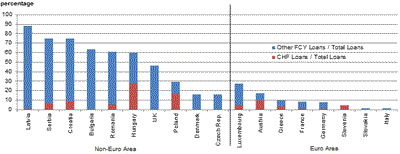

Table 1 lists the measures for systemic risk across European countries as of the third quarter of 2011. It also shows the currency breakdown of systemic risk arising from CHF loans and other foreign currency loans. It is worth noting that there is substantial cross-country variation in systemic risk. While systemic risk is relatively low for the Eurozone countries, it is fairly high for some non-Eurozone countries. For the non-Eurozone countries this high risk is not due to CHF loans, which have received considerable attention from the policymakers and the press. The data source does not allow for a further currency breakdown of foreign currency loans, but one can conjecture that euro loans are behind the systemic risk in the majority of the non-Eurozone countries.

Table 1. Systemic-risk indeces in Europe as of 2001Q3 due to foreign-currency loans

Note: Systemic risk = systemic risk due to CHF loans + systemic risk due to other FCY loans. A higher value indicates higher systemic risk. CHF, Swiss francs; FCY, foreign currency; NA, not available.

Source: Author’s own calculations based on CHF Lending Monitor data.

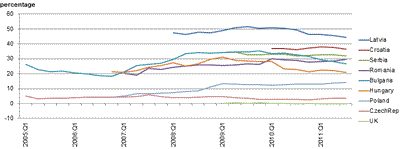

Figure 2 shows the time evolution of systemic risk in the non-Eurozone between quarter on of 2005 and quarter three of 2011. Note that there is an upward trend in a few countries in the first half of the sample period. However, since 2009, systemic risk is highly persistent and not volatile for the majority of the countries. A slow decline can be observed for Hungary, Latvia, and Bulgaria, reversing their previous upward trend.

Figure 2. Evolution of systemic risk in the non-Eurozone

(click to enlarge)

Source: Author’s calculations based on CHF lending data.

Conclusion

Systemic risk measures show that foreign currency loans to the non-banking sector create substantial risks to the banking sector from a ‘common market shock’perspective. High persistence and low volatility of the systemic risk measures indicate that short-term policies would be unable to swiftly reduce this risk. Encouragement of local-currency borrowing along with macro-prudential policies can help mitigate the risk in the long run, as recently promoted by an EBRD initiative.

References

•De Bandt, Olivier and Philipp Hartmann (2000), “Systemic Risk: A Survey”, ECB Working Paper, No. 35, European Central Bank.

•Georg, Co-Pierre (2011a), “Basel III and Systemic Risk Regulation – What Way Forward? “, Working Papers on Global Financial Markets, No. 17-2011, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena.

•Georg, Co-Pierre (2011b), “The Effect of the Interbank Network Structure on Contagion and Common Shocks”, Discussion Paper Series 2: Banking and Financial Studies, No. 12, Deutsche Bundesbank.

•Ranciere, Romain, Aaron Tornell, and Athanasios Vamvakidis, “Currency Mismatch, Systemic Risk and Growth in Emerging Europe”, Economic Policy, October 2010, Vol. 25, No. 64, pages 597-658.

•Yeşin, Pınar (2013), “Foreign Currency Loans and Systemic Risk in Europe”, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review, Vol. 95, Issue 3, May/June 2013, pages 219-235.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply