Having promised to do ‘whatever it takes’ to ensure the survival of the euro, the ECB now faces the problem of record high unemployment combined with a strong currency. There is accumulating evidence that the ECB is more willing to fight currency appreciation than the Bundesbank would have been. Capital inflows have been a key source of recent upward pressure on the euro. Should this continue, the ECB may need to intervene more aggressively in order to promote economic recovery in the Eurozone.

A new battle for the ECB to fight

Last year, the ECB entered an existential battle for the euro. By promising to do ‘whatever it takes’ to safeguard the euro, the ECB managed to calm sovereign debt markets and engineer a much-needed easing of overall credit conditions in the Eurozone.

Unfortunately, the Eurozone economy remains stuck in a slump. Eurozone growth momentum was only marginally positive in Q3 at 0.1% quarter-on-quarter, and Italy and France continue to struggle with negative GDP dynamics. In year-on-year terms, Eurozone GDP is still negative (-0.4%), and the unemployment rate stands at 12.2% – a record high. There are currently 19.4 million unemployed in the Eurozone – 6.8 million more than in 2008.

Moreover, not all components of Eurozone financial conditions are improving. Over the last twelve months, the ECB’s trade-weighted euro index is up around 6%. All else equal, this could pose a significant drag on GDP in 2014.1 Using simulation results from the ECB’s Area Wide Model, the impact on Eurozone growth could be in the region of 0.4 percentage points in the first year following such a currency appreciation (Mauro et al. 2008).

The combination of a strong currency and an extreme unemployment problem leaves the ECB with a new challenge. The challenge is no longer the survival of the euro. Ironically the challenge is now the common currency’s strength. The ECB’s next battle may not be about saving the euro, but about reducing its value.

The Eurozone and global currency wars

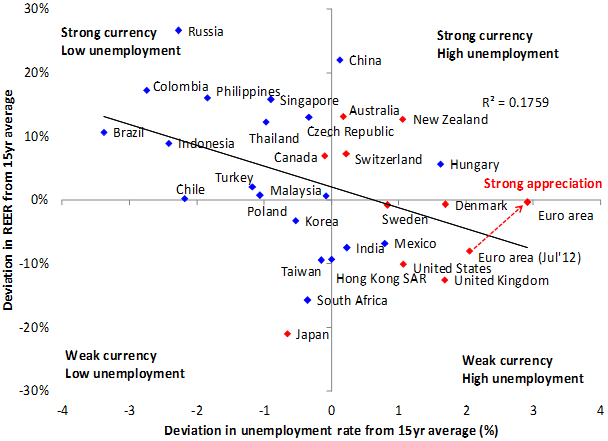

Figure 1 illustrates where the Eurozone stands in a global comparison in terms of the level of unemployment and the level of the euro’s Real Effective Exchange Rate.

Figure 1. Global currency war scatter plot

Note: Data points as of 31 October 2013. Eurozone also shown for July 2012.

When compared to the 30 largest major and emerging-market economies in the world, the Eurozone is heading quickly towards the problematic quadrant of the scatter plot.

- The Eurozone has the largest unemployment problem of any major developed market or emerging market economy (relative to its own history). Unemployment is about three percentage points above its historical average.

- The Eurozone has an appreciating currency. The level of the Real Effective Exchange Rate is currently in line with its historical average, but further appreciation – in line with the trend of the last year – would push it into ‘strong territory’ relative to its history.

The countries in this northeastern part of the scatter plot – with high unemployment and a strong currency – are typically the ones complaining about their currency.2 In the terminology of the global financial press, countries in this quadrant are the ones likely to enter a currency war.

The ECB compared to the Bundesbank

Based on the ECB’s surprise decision to lower its reference rate to 0.25% at the November meeting, one could argue that the ECB has already entered the battle to push the euro lower. The rate cut followed a significant appreciation of the euro since September, and the euro’s strength is playing into both the ECB’s growth and inflation projections (we will know by how much after the forecast revision in December).

While the ECB follows a single mandate (an asymmetric inflation target), there is accumulating evidence that the ECB may be less tolerant of a strong currency and deflationary risk than the Bundesbank would have been historically.

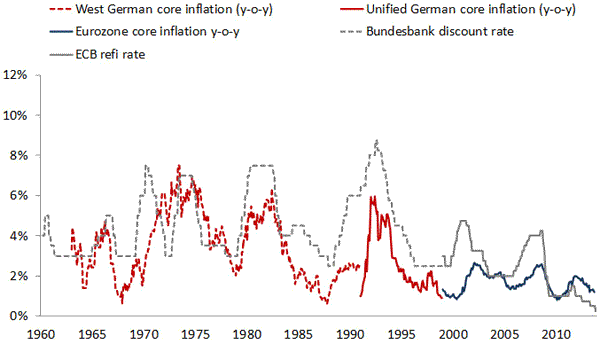

Figure 2. German and Eurozone core inflation and reference rates

Source: Bundesbank, ECB, Haver, Nomura.

First, it has been leaked that the German members of the ECB’s Governing Council – as well as other northern European members – voted against the rate cut on 7 November (Wolf 2013).

Second, the ECB’s behaviour is increasingly deviating from that of the Bundesbank in the past. In the 1980s, the Bundesbank tolerated very low core inflation without resorting to comparable ‘emergency easing’ measures, for example. As shown in Figure 2, German core inflation dropped below the current level in the Eurozone (0.8%) on several occasions in the pre-euro period without triggering dramatic monetary policy responses.3

Third, ECB officials have recently indicated they are open to further monetary easing. For example, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal on 13 November, ECB Chief Economist Peter Praet mentioned the possibility of a negative deposit rate, and even suggested that asset purchases were an option if needed to fight off deflation risk (Wall Street Journal 2013).

All told, there is accumulating evidence that the ECB is becoming more proactive – including taking steps to avoid excessive currency strength. It is all a part of the euro’s evolution – from a currency built to mirror the key characteristics of the DEM, towards a more pragmatic currency construct, better suited to deliver on the needs of the Eurozone economies overall (Nordvig 2013).

Conclusion

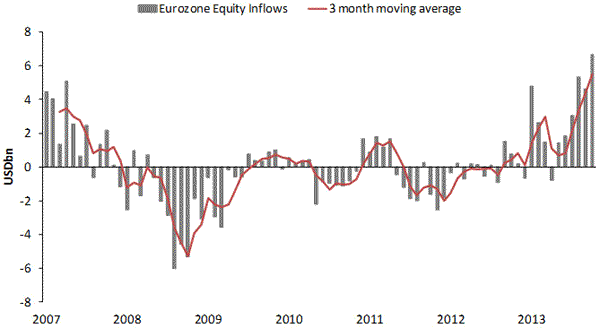

Strong foreign capital inflows into Eurozone equity markets have been a key source of upward pressure on the euro over the last several months. Should this continue, there is likely to be a need for the ECB to become more aggressive on monetary policy (both relative to the US and Japan) to avoid excessive euro appreciation. Failure to react would create an additional headwind for Eurozone growth at a time when the recovery remains very weak and fragile.

There is already some evidence that the ECB is deviating from the old ways of the Bundesbank. However, more will be needed to avoid an excessively strong euro and excessively tight overall financial conditions. The ECB is highly unlikely to intervene directly in the currency market any time soon. It will likely play by the rules of the G7 as long as possible, and hence avoid verbal intervention as well for the time being.4

However, as the currency continues to strengthen and moves into ‘strong territory’ relative to its history, the negative growth effects may eventually become intolerable. The basic challenge for the ECB is to ease overall financial conditions to the benefit of Eurozone growth. So far, easier credit conditions have pulled in foreign capital and caused the currency component of financial conditions to tighten. The ECB may need to enter the currency war more actively to secure a more competitive euro in 2014, and thereby support a more robust economic recovery.

Figure 3. Eurozone equity inflow trends (proxied by mutual fund flows)

Source: EPFR, Nomura. Note: Figures show foreign buying of Eurozone equities. Sample is not comparable to overall balance of payments figures, as coverage is only partial, but figures are more up-to-date, and provides a sense of changes over time.

References

•Di Mauro, F, R Rüffer, and I Bunda (2008), “The Changing Role of the Exchange Rate in a Globalised Economy”, ECB Occasional Paper 94, September.

•Nordvig, Jens (2013), The Fall of the Euro: Reinventing the Eurozone and the Future of Global Investing, McGraw-Hill, October.

•Wolf, Martin (2013), “Why Draghi was right to cut rates”, Financial Times, 12 November.

•The Wall Street Journal (2013), “ECB’s Praet: All Options on Table”, 13 November.

______

1 The all-else-equal assumption embedded in such a model is often a difficult one. It clearly matters why the exchange rate is stronger. Is it due to strong export performance (which would be clearly growth-positive)? Or is it due to strong inflows into Eurozone stock markets (which may have a less strong impact on growth)? There is evidence that strong portfolio inflows into Eurozone equity markets is a key driver, which may mean that the cause of the currency appreciation has more to do with global asset allocation shifts than something directly growth-supportive.

2 For example, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Reserve Bank of Australia – both facing currency strength and unemployment above the historical average – have been trying to talk their currencies down this year, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has also been intervening directly in the currency market.

3 We have entered a new era for monetary policy globally in recent years, characterised by prevalent use of unorthodox policy measures. Nevertheless, the ECB seems more willing to move in this direction than the Bundesbank would have been.

4 Officially, the euro-group is responsible for currency policy in the European context, while the ECB is in charge of implementing this policy. In reality, the ECB is likely to play a more prominent role – beyond mere implementation.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply