The minutes of the October FOMC meeting leave little doubt that the Fed increasingly desires to end the asset purchase program, enough so to contemplate tapering regardless of seeing satisfactory improvement in labor markets. It is that desire – or perhaps desperation – that puts an element of random chance into the policymaking process and keeps the expectation of near-term tapering alive despite efforts of policymakers to reassure market participants that it is all data dependent. Trouble with that story is simple – it is not only data dependent. The Fed has already admitted as much.

Policy planning and communication strategy were the hot topic of this FOMC meeting, and the discussion of the specifics of the asset purchase program began with:

During this general discussion of policy strategy and tactics, participants reviewed issues specific to the Committee’s asset purchase program. They generally expected that the data would prove consistent with the Committee’s outlook for ongoing improvement in labor market conditions and would thus warrant trimming the pace of purchases in coming months.

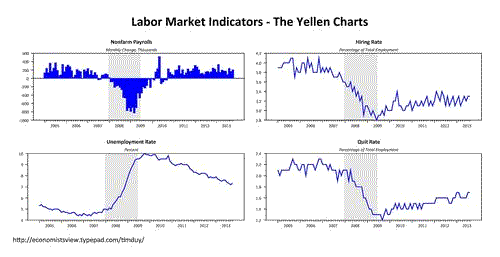

The mythical taper – just a few months away. And it will always be just a few months away given the broad weakness in the labor chart. Recall the Yellen Charts:

Unless they narrow their focus to only the unemployment rate, the argument to taper is challenged to say the least. It is even more challenged considering inflation indicators. Knowing that the data continuously refuses to cooperate, the Fed explores plan B:

However, participants also considered scenarios under which it might, at some stage, be appropriate to begin to wind down the program before an unambiguous further improvement in the outlook was apparent.

To be sure, some doves shrieked:

A couple of participants thought it premature to focus on this latter eventuality, observing that the purchase program had been effective and that more time was needed to assess the outlook for the labor market and inflation; moreover, international comparisons suggested that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet retained ample capacity relative to the scale of the U.S. economy.

It may be premature, but if they are going to go down that road, they had better have an explanation:

Nonetheless, some participants noted that, if the Committee were going to contemplate cutting purchases in the future based on criteria other than improvement in the labor market outlook, such as concerns about the efficacy or costs of further asset purchases, it would need to communicate effectively about those other criteria.

And there it is – the missing piece. We know the Fed has been looking to pull the plug on asset purchases, they just haven’t explained why. Well, not exactly. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke was more direct on the subject in his speech this week:

..though a strong majority of FOMC members believes that both the forward rate guidance and the LSAPs are helping to support the recovery, we are somewhat less certain about the magnitudes of the effects on financial conditions and the economy of changes in the pace of purchases or in the accumulated stock of assets on the Fed’s balance sheet. Moreover, economists do not have as good an understanding as we would like of the factors determining term premiums; indeed, as we saw earlier this year, hard-to-predict shifts in term premiums can be a source of significant volatility in interest rates and financial conditions. LSAPs have other drawbacks not associated with forward rate guidance, including the risk of impairing the functioning of securities markets and the extra complexities for the Fed of operating with a much larger balance sheet, although I see both of these issues as manageable.

The problem with this cost and efficacy approach is that new “costs” could pop up at anytime. Definitely a policy wild card, and one the Fed is increasingly considering using.

The desire to taper also drives the frantic search for alternative modes of accommodation:

In those circumstances, it might well be appropriate to offset the effects of reduced purchases by undertaking alternative actions to provide accommodation at the same time.

One such way would be enhanced forward guidance:

As part of the planning discussion, participants also examined several possibilities for clarifying or strengthening the forward guidance for the federal funds rate, including by providing additional information about the likely path of the rate either after one of the economic thresholds in the current guidance was reached or after the funds rate target was eventually raised from its current, exceptionally low level.

There was not, however, widespread support for changing the thresholds:

A couple of participants favored simply reducing the 6-1/2 percent unemployment rate threshold, but others noted that such a change might raise concerns about the durability of the Committee’s commitment to the thresholds. Participants also weighed the merits of stating that, even after the unemployment rate dropped below 6-1/2 percent, the target for the federal funds rate would not be raised so long as the inflation rate was projected to run below a given level. In general, the benefits of adding this kind of quantitative floor for inflation were viewed as uncertain and likely to be rather modest, and communicating it could present challenges, but a few participants remained favorably inclined toward it.

Instead, the favored path seems to be incorporating what we have been hearing from policymakers more directly in the FOMC statement:

Several participants concluded that providing additional qualitative information on the Committee’s intentions regarding the federal funds rate after the unemployment threshold was reached could be more helpful. Such guidance could indicate the range of information that the Committee would consider in evaluating when it would be appropriate to raise the federal funds rate. Alternatively, the policy statement could indicate that even after the first increase in the federal funds rate target, the Committee anticipated keeping the rate below its longer-run equilibrium value for some time, as economic headwinds were likely to diminish only slowly.

Essentially, a commitment to ignore the thresholds without changing the thresholds. Later, the Fed circled back to an oldy but a goody:

Participants also discussed a range of possible actions that could be considered if the Committee wished to signal its intention to keep short-term rates low or reinforce the forward guidance on the federal funds rate. For example, most participants thought that a reduction by the Board of Governors in the interest rate paid on excess reserves could be worth considering at some stage, although the benefits of such a step were generally seen as likely to be small except possibly as a signal of policy intentions.

Notice a theme above? Fed officials have little faith in any of their alternatives. They want to pull back from quantitative easing, fearing that the costs will turn against them soon, yet have little to offer in return. Not good – it is almost as if the Fed is beginning to believe that they are near the end of their rope.

Interestingly, one of the costs of quantitative easing seems to be the inability to exit quantitative easing. This was revealed in today’s bond market sell-off after the minutes were released. Despite the Fed’s repeated efforts to use forward guidance to hold down rates, despite repeated reassurances that tapering is not tightening, Treasury yields gain almost 10 basis points at the 10 year horizon on even a whisper of tapering – and this after Bernanke’s dovish speech and Vice Chair Janet Yellen’s (perceived) dovish Senate hearing last week. Fine tuning policy with a tool of uncertain force is something of a challenge. Sufficient faith in an alternative tool would help clear the way for tapering despite this uncertainty, but after reading these minutes, I am somewhat concerned such faith is lacking.

Bottom Line: Clear evidence of the space we have been in for months. The Fed wants to taper, and is becoming increasingly nervous they will need to pull the trigger on that option before the data allows. That means that tapering is not data dependent. That means the policy deck is stacked with at least one wild card. And that sounds like a recipe for the kind of volatility the Fed is looking to avoid.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply