Matthew Klein rebuts Ryan Avent (my sympathetic position here), and makes some good points. That said, I still think the FOMC is kind of a clown show right now. A significant problem is that they can’t communicate effectively, either internally or externally, that the Fed is now operating under a triple mandate. They are struggling with the resulting trade-offs and while the struggle is public, it is not explicit. Klein does a much better job than the totality of the FOMC in bringing this issue to light.

Klein summarizes his objection to Avent with:

After reading this narrative, the Economist’s Ryan Avent concluded that the U.S. central bank is a “clown show.” While there are plenty of legitimate criticisms one can make about Fed policymaking over the years, Avent’s misses the mark. This sort of simplistic reasoning assumes central bankers only need to manage a single trade-off between the rate of consumer price inflation and the level of joblessness. The real world, however, is far more complex.

Why is it more complex than the dual mandate?

While the precise meanings of “maximum employment” and “stable prices” remain undefined, the biggest source of ambiguity is the time-frame. Certain policies might temporarily suppress the unemployment rate but end up sowing the seeds of trouble down the road.

For example, the Fed’s accommodative policies in the 2000s may have mitigated the collapse in business investment after the end of the tech bubble, but this brief reprieve came at the cost of soaring private indebtedness and a financial sector that blew itself up.

What is the specific problem today?

Many Fed policymakers appreciate the complexity of these trade-offs and are trying to grapple with them in the context of today’s environment. High unemployment and sluggish increases in consumer prices would suggest that the Fed should step on the gas. On the other hand, risk-takers in the financial sector may end up overextending themselves and sow the seeds of another crisis.

And there lies the communication problem. The Fed has largely communicated its policy objective on the basis of two variables, inflation and unemployment. The Evan’s Rule, from the last FOMC statement:

In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.

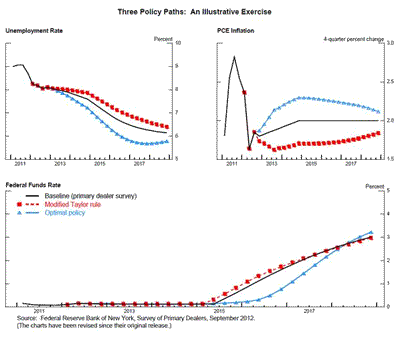

And note that Yellen’s much heralded optimal control strategy explicitly reduces policy to a near-term inflation/unemployment trade-off:

(click to enlarge)

“Financial stability” is not identified here. And it makes only a passing appearance in the statement:

In determining how long to maintain a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy, the Committee will also consider other information, including additional measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments.

But even that statement is followed up by a return to the dual mandate:

When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent.

We do of course still have the “costs and benefits” clause of the asset purchase program:

Asset purchases are not on a preset course, and the Committee’s decisions about their pace will remain contingent on the Committee’s economic outlook as well as its assessment of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases.

But even here we have precious few explanations of the costs and risks of asset purchases and few on the FOMC willing to say asset purchases are ineffective.

In short, the FOMC’s public face is largely focused on the unemployment/inflation trade off. But Klein’s correct, something else is brewing under the surface of policy. Take for example today’s comments by Vice Chair Janet Yellen. Most focused on:

The mandate of the Federal Reserve is to serve all the American people, and too many Americans still can’t find a job and worry how they will pay their bills and provide for their families. The Federal Reserve can help, if it does its job effectively. We can help ensure that everyone has the opportunity to work hard and build a better life.

But read the next two lines:

We can ensure that inflation remains in check and doesn’t undermine the benefits of a growing economy. We can and must safeguard the financial system.

Triple mandate – maximum sustainable employment, price stability, and financial stability.

Perhaps if monetary policy could focus solely on the first two, while macroprudential policy takes on the last, then the triple mandate would not pose a major challenge. But, alas, as Klein notes, this is not the case. Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Stein explicitly identified the issue in February:

Nevertheless, as we move forward, I believe it will be important to keep an open mind and avoid adhering to the decoupling philosophy too rigidly. In spite of the caveats I just described, I can imagine situations where it might make sense to enlist monetary policy tools in the pursuit of financial stability.

Consider the tradeoffs now in play. More so than in the past, the Fed is aware that by promoting maximum employment and price stability, they may be promoting financial instability. So they may need to take action in the near term to promote financial stability at the expense of the first two objectives. Indeed, this is exactly what happened this year with regards to the tapering talk. Consider Stein’s September speech:

Having said all of this, I believe we are currently in a pretty good place with respect to the pricing of interest rate risk. The movement in Treasury rates that we have seen since early May has led to somewhat tighter financial conditions in certain sectors–most notably the mortgage market–but has also brought term premiums closer into line with historical norms, and thereby has arguably reduced the risk of a more damaging upward spike at some future date. On net, I believe the adjustment has been a healthy one.

The tighter financial conditions may have slowed progress on the employment/price stability mandates, but improved the financial stability outlook. One instrument, three objectives. Won’t be able to make everyone happy all of the time.

The introduction of a third mandate into the policymaking process, however, has not been communicated very well. As a consequence, in my opinion, market participants cannot determine the bar to tapering. And, arguably, it leaves an unaccounted variable floating around in Yellen’s optimal control strategy that could influence the path of interest rates. And if low inflation environments breed financial instability, will the Fed sacrifice the inflation target or the employment mandate? There are lots and lots of questions here. Klein is right – it isn’t easy.

That said, we should not have to pull this debate out of odd speeches here and there. Leaving this on the back of Stein’s infrequent speeches is not enough. It seems clear that financial stability objectives are now part of the Fed’s reaction function. Policymakers need to bring this issue to the forefront, the sooner the better.

Bottom Line: Monetary policymakers are viewing financial stability as an important element of sustaining maximum employment and stable prices over the course of a business cycle. The challenge is that this involves a new trade-off in the monetary policy process that they are struggling to understand. Unfortunately, the public debate they are carrying on is somewhat clownish in that it is sending conflicting signals about the path of monetary policy. This is really not surprising. What exactly is the Fed’s reaction function if we throw financial stability into the mix? They don’t know any better than we do. I don’t even think monetary policymakers even share a common framework when it comes to incorporating financial stability into the reaction function. This, I think, is an opportunity for a strong leader to chart a course for the Fed that while encouraging internal discussion works to keep a consistent external message. I am hoping Yellen will serve that role.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

The Fed is a fraud. No only are their death’s door interest rates for 5 years running a slap in the face of those who call this jobless “recovery” prosperity, but puts the entire onus for a recovery on those least able to afford it: the middle class.

These people can’t afford to risk their wealth in an overpriced yo-yo securities market, and therefore have no way to make their investable funds grow at interest which would certainly provide a source for real stimulus to our Fed crippled economy. Someone like you should confront these bungling tyrants with the economic fact that monetary policy can’t fight fiscal problems; as their shabby record attests.