Martin Feldstein will give you three possible reasons why—to some surprise, I gather—the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided two weeks back to not adjust the pace of its asset purchases:

One possibility is that Bernanke and the other FOMC leaders… never intended to start tapering…

A second possible explanation is that Bernanke and other Fed leaders were indeed anticipating that they would begin tapering QE in September but were startled at how rapidly long-term rates had risen in response to their earlier statements…

The third scenario is that economic activity was clearly slowing, with the future pace of activity therefore vulnerable to even higher interest rates.

Speaking only for myself, I choose Feldstein’s third option. He goes a good way to making the case himself:

The annualized GDP growth rate in the first half of 2013 was just 1.8%, and final sales were up by only 1.2%. Although there are no official GDP estimates for the third quarter, private-sector assessments anticipate no acceleration in growth, putting the economy on a path that will keep this year’s output gain at well under 2%.

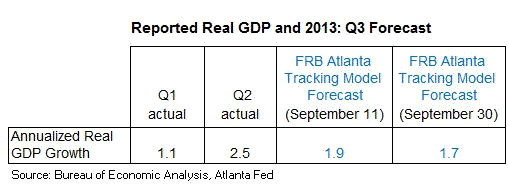

That unfortunate story was pretty clear on the eve of the FOMC meeting—in particular, the lack of evidence that growth in the second half of the year would be an improvement on the already disappointing pace of the first half. Our own internal “nowcast” tracking model was suggesting third-quarter GDP growth in the neighborhood of the sub-2 percent growth that Feldstein cites. And as this table shows, things have not improved since:

These facts, of course, were reflected in the downgrade of the 2013 growth forecasts published in FOMC participants’ Summary of Economic Projections. But that is not all, as Professor Feldstein reports:

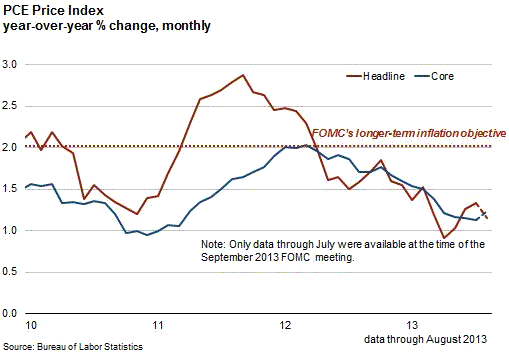

In addition, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation was much lower than its 2% target. The annual price index for personal consumer expenditure, excluding food and energy, has been rising for several months at a rate of just 1.2%, increasing the possibility of a slide into deflation.

And even if you don’t go in for inflation measures that exclude food and energy, it doesn’t much matter, because all-in inflation was, and still is, also running well below that 2 percent target:

Though the August personal consumption expenditures price report finally provided a slight uptick in year-over-year core inflation, there was not even that scant hint of a return to the 2 percent inflation target by FOMC meeting time.

And that was looking a lot like strike number two to me. As Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke explained at the post-meeting press conference, repeating the criteria for adjustments to the FOMC asset purchase program that he laid out in June:

We have a three-part baseline projection which involves increasing growth…, continuing gains in the labor market, and inflation moving back towards objective… we’ll be looking to see if the data confirm that basic outlook.

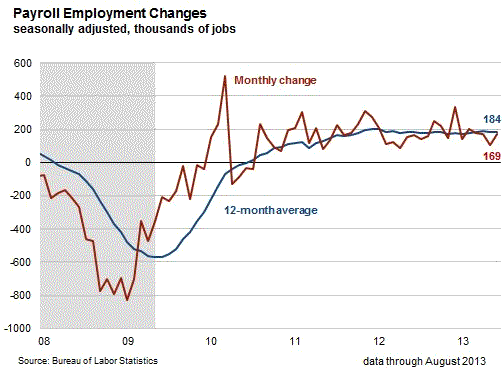

Of the remaining element of the three-part baseline, it is true that 12-month average monthly job gains looked pretty much like they did in June, when the talk of taper got serious:

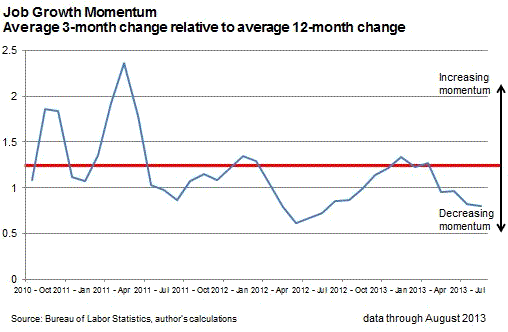

But the momentum—which I measure here as the ratio of three-month average monthly job gains to the 12-month average—was clearly in the downward direction:

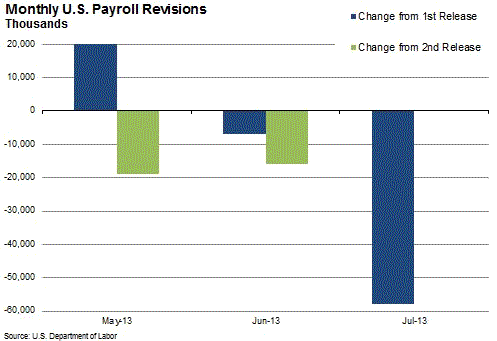

What’s more, the revisions in prior months’ employment statistics were running in the wrong direction:

As a rule, forecasters don’t sweat being wrong. That comes with the territory. But when you are persistently wrong in the same direction, it is time to worry at least a bit.

So, what do we have, then?

- Inflation is low relative to the FOMC’s objective—and has not moved in the direction of that objective with any conviction.

- GDP growth has disappointed, with the anticipated pickup in second-half growth nowhere in sight.

- “Continuing gains in the labor market” at the pace seen earlier in the year are looking a little shaky.

I find it pretty easy to see how this fails to add up to satisfaction of the three-part economic conditionality laid out in June by the Chairman (on behalf of the FOMC).

One could argue, I suppose, that the FOMC’s explicit tying of asset purchases to improvement in the labor market makes it first among equals in the three-part test (as long as inflation is relatively stable), that similar downward momentum on the job front arose and disappeared in the summer of 2012, and that with a little patience things will appear on track.

Maybe. But I would point out that the reversal of negative momentum in the labor market the summer before was accompanied by the initiation of “QE3” (or at least the MBS part of QE3). You can draw your own conclusions about causality, but there is a fairly convincing case to be made for the proposition that, with the data in hand at the time, a wait-and-see decision was what patience dictated.

That, of course, begs the main question posed in Feldstein’s article: When will it be time to taper? On that, and in the spirit of baseball playoff season, get your scorecard here.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply