One report does not – or, at least, should not – dramatically impact the Fed’s policymaking process. Indeed, the employment report is arguably an outlier in a week otherwise dominated by solid data. Both the manufacturing and services flavors of the ISM report were decidedly positive, as was the initial claims release. That said, it seems hard to deny that the August employment report is like a wrench thrown into the Fed’s tapering machine.

The headline number of !69k jobs gained was in itself on the soft-side of expectations, especially given the generally positive employment indicators from earlier in this week. Jim Tankersly points out, however, that the number might be a reflecting a temporary loss of 22k jobs in the adult entertainment business. It is actually reasonable to expect that the Fed would try to look through that kind of event as if it were, for example, an autoworkers strike (just like naked autoworkers, I suppose). Now I am interested to see if this shows up in the minutes, or if we need to wait five years before the transcripts are released. (UPDATE: Josh Barro ruins a perfectly good story with facts).

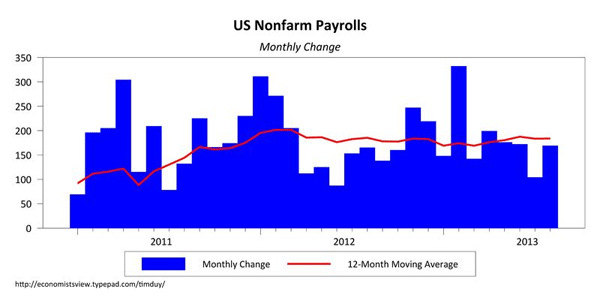

I would say that given the Fed’s current inclinations, anything above 150k is a tapering number. Of course, downward revisions to the previous two months make recent trends look even more lackluster:

That said, the 12-month average continues to track around 180k jobs a month, which is enough to steadily push down the unemployment rate in the context of declining labor force participation rates. And therein lies the grey zone for policymakers. Are Fed officials inclined to believe that, absent a financial crisis, asset purchases have limited impact on the pace of job creation and the decline in the labor force participation rate is largely structural? If so, they could easily decide that the cost/benefit analysis no longer supports additional asset purchases.

San Francisco Federal Reserve President John WIlliams moved in this direction this week when he argued that the unemployment rate was still the single best indicator of labor market health. Compare this Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans today. After outlining his expectation that asset purchases would end by mid-2014, he says:

Is it possible that it might be appropriate to end QE3 earlier? Yes — absolutely — if the labor market improved faster and that was supported by stronger growth. Under these conditions, if the unemployment rate fell to 7 percent by December 2013, labor force participation was healthy and inflation was running higher than today, then I would endorse a quicker end to our asset purchases.

The unemployment rate today is only 7.3%. Getting to 7% by the end of the year is not exactly a big trick. And getting inflation “higher than today” is not exactly a high bar. So really the only barrier to a more rapid end to asset purchases for Evans is what he defines as “healthy” labor force participation. And the more that he and other come to view the decline in labor force participation as structural, the more they will want to accelerate the pace of tapering.

Or, to put it another way, the preponderance of the data likely still points toward tapering, with only the pace in question and the pace probably has more to do with their view of structural impediments in labor markets than anything else. After all, the 7% threshold for asset purchases is already staring us in the face while there is evidence that the inflation tide is turning; only labor force participation is causing the Fed to hesitate this point.

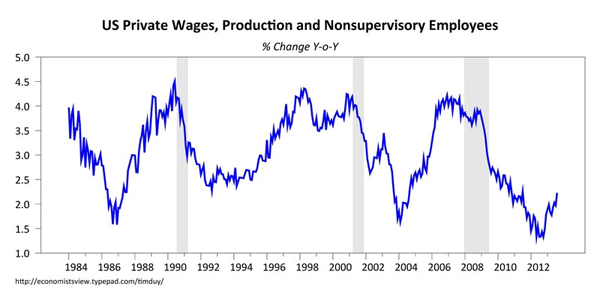

Also arguing for tapering is this:

Falling wage growth indicated weak cyclical demand in labor markets. If wages are turning upward – and by this measure they have – then cyclical demand is improving. Rising wages will only further the belief that the unemployment rate is indeed the best measure to follow and the declining labor force participation rate is largely a structural phenomenon.

Recall also Williams said that he believed that forward guidance should take precedence over asset purchases in the future. If they move away from asset purchases as expected, the Fed will place more emphasis on forward guidance to soften the blow. Evans today:

Suppose the unemployment rate reached 6-1/2 percent and inflation were 1-1/2 percent. One-and-a-half percent strikes me as much too low relative to our 2 percent target, especially since inflation has been running below 2 percent for quite a long time. I think that in this situation, it would be appropriate to hold the funds rate at zero to get inflation confidently moving back up toward 2 percent. I can easily envision certain circumstances in which the unemployment rate could go below 6 percent before we moved the funds rate up.

This scenario would push the date of the first rate hike out to 2016 given that Evans’ baseline forecast is a hike in late 2015. Remember that the timing of the first rate hike is the important question. If the Fed were to make a large cut in asset purchases, the market interpretation would be that the first rate hike would be sooner than expected. A smaller cut would indicate the opposite.

And with regards to the issue of the first rate hike, keep watching wage growth. Weak wage growth was undoubtedly been a weight on inflation. If that weight has lifted, then we would expect inflation to creep higher toward the 2% mark, and with it the Fed’s inclination to withdraw accommodation sooner than expected.

Bottom Line: I still look for tapering at the next meeting, albeit tapering-light. Overall, the data remains broadly consistent with the Fed’s forecast, and the unemployment rate is moving low enough to push the Fed toward withdrawing accommodation. The Fed will worry that delaying tapering now will only put them at risk of having to taper more aggressively later, and such a scenario would be interpreted by financial markets as stepping up the timing of the first rate hike. They can get the first move out of the way this month with a small cut to the pace of asset purchases and then reassess the situation over the next six weeks. Expect more emphasis on forward guidance on interest rates.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply