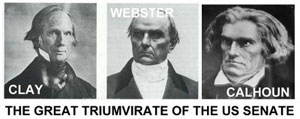

All three senators of the Great Triumverate of Senate history at one point in their careers endorsed stronger limits on Senate debate. So I have no doubt that their ghosts had a great week: Eavesdropping on the senators in their chamber Monday night and reading all the good stuff that was written about how and why the Senate defused its nuclear bomb. I think we can count this episode, as Greg Wawro and Eric Schickler suggested on the Monkey Cage, as a case in which the majority offered a credible threat to impose majority rule on executive branch nominations, and the minority folded. Wawro and Schickler conclude a clear lesson from the week’s events: “A simple majority in the Senate has the power – and indeed has long had the power – to change how the institution operates.” Similarly, Ezra Klein noted that “The majority took out a nuke, put it on the table, and made clear they can detonate it whenever they feel like.”

All three senators of the Great Triumverate of Senate history at one point in their careers endorsed stronger limits on Senate debate. So I have no doubt that their ghosts had a great week: Eavesdropping on the senators in their chamber Monday night and reading all the good stuff that was written about how and why the Senate defused its nuclear bomb. I think we can count this episode, as Greg Wawro and Eric Schickler suggested on the Monkey Cage, as a case in which the majority offered a credible threat to impose majority rule on executive branch nominations, and the minority folded. Wawro and Schickler conclude a clear lesson from the week’s events: “A simple majority in the Senate has the power – and indeed has long had the power – to change how the institution operates.” Similarly, Ezra Klein noted that “The majority took out a nuke, put it on the table, and made clear they can detonate it whenever they feel like.”

Before we seal the history books on this week’s events, I think there’s still some nuance about the nuclear option that’s worth considering. No doubt, the reform-by-ruling strategy that Majority leader Harry Reid brushed off has (almost) always been technically feasible. But I think we’ve learned a bit more this week about the conditions under which the nuclear option will be politically feasible.

Think first about the 2005 episode in which Majority leader Bill Frist threatened to go nuclear over Democrats’ filibusters of judicial nominations. Most reporting afterwards noted that the minority came out ahead of the majority: Republicans secured confirmation of three contested nominees, Democrats killed seven others, and the nuclear option was taken off the table for the duration of the Congress. Why the majority loss? (Or at best an even draw?) Reporting suggested that Frist’s threat was never credible because a divided GOP majority undermined its leader: The seven GOP senators, including John McCain, who signed the Gang of 14 agreement, deprived Frist of the votes to go nuclear. Absent a politically credible threat, the minority gave up relatively little in the Gang of 14 deal.

In contrast, Harry Reid this week had clearly locked up 51 (if not 53) votes. Had Republicans not deemed Democrats’ determination to go forward credible, I doubt we would have seen the minority cave (securing only the arguably face-saving gesture of a new pair of labor-favored NLRB nominees for an old pair of labor-favored nominees). Why the different outcomes? Reid’s strategy tells us a bit about the conditionality of the nuclear option:

First, the more narrowly targeted the nuclear gambit, the more credible it seems to be. Reid’s limited targeting of executive branch nominees made the reform by ruling strategy more palatable to Democrats. Narrowly tailoring the reach of the proposal seems to have secured wavering Democrats’ votes. Indeed, as best as I can tell, Reid secured the unified support of his caucus by explicitly excluding judicial nominations from the reach of his nuclear gambit. (Excluding judges also no doubt helped Democrats politically to justify their own nuclear rush given their opposition to Republican efforts to go nuclear in 2005.)

Second, the political feasibility of the nuclear option seems conditioned on the behavior of the minority. Strident overreaching by the Republicans—opposing nominees not on the basis of qualifications or policy views but as leverage to renegotiate (CFPB) or undermine (NLRB) an agency—helped Democrats to paint the GOP as going a step too far in a Senate parliamentary arms race. (On GOP overreach, see Jon Bernstein’s piece here.) Exhibit A for GOP overreach starts and ends with Lindsey Graham’s “we were wrong” admission. Such GOP behavior deflected accusations that Democrats were “power-hungry” aggressors in the nuclear fight. The ability to shift blame to the GOP likely increased the political feasibility of Reid’s nuclear gambit.

Third, keep in mind that the CFPB, NLRB, EPA and Labor department are critical institutions for pursuing core Democratic policy interests—protecting the environment and the interests of workers and consumers. Of course, that’s precisely why Republicans targeted these nominees in the first place. But I doubt Democrats would have gone to the mat to secure confirmation of a favored head of the IRS or USDA. Democrats would have had a hard time mustering a politically credible threat on behalf of such nominees.

I think these dimensions of the Senate’s brush with going nuclear this past week are useful reminders of the conditionality of the majority’s nuclear weapon. I’m not so sure that the nuke remains on the table to be detonated anytime the Democrats would like—except for similarly constrained targets. In fact, I wonder if Reid’s narrow targeting of executive branch nominees might have made judicial filibusters even more likely and harder to rein in. By drawing a clear line this past week between confirming “the president’s team” and confirming lifetime appointments to the courts, Democrats might have made it easier for Republicans to justify obstruction of appellate court nominees. In other words, Reid’s robust success might prove to be a double-edged sword.

Having said that, GOP arguments against Obama’s three recent nominees for the D.C. Court of Appeals have a ring of overreach in them: It’s not the nominees they object to, but the size of the court on which they would serve. We’ll see if such an argument is more successful when lodged against judicial nominees soon enough.

Leave a Reply