The conventional wisdom is that the big jump in interest rates since the beginning of May is the result of a poorly conceived or poorly communicated shift in policy by the U.S. Federal Reserve. The conventional wisdom is wrong.

Prior to the Great Recession, I thought we had all agreed on the practical limits on the Fed’s capabilities. We understood that to some extent the Fed could control the short-term interest rate by changing the supply of reserves available to the banking system. But we also understood that the Fed’s influence over longer-term interest rates was much less immediate and direct. The Fed can communicate its long-run inflation objectives, and certainly the 10-year inflation rate is a very important determinant of long-term yields. But regardless of what the Fed may say about its 10-year inflation goals, the market would form its own view of whether the Fed could or would achieve those. Other determinants of long-term yields, such as the term premium, long-run economic growth rate, and global saving and investment decisions were understood to be even farther beyond those things that the Fed can hope to control.

In the fall of 2008, the interest rate on U.S. overnight loans fell essentially to zero, and reserves ballooned far beyond levels that banks needed to meet reserve requirements. These developments meant that the Fed lost its most important policy tool for influencing interest rates. The Fed was forced to rely on even blunter instruments for conducting policy, such as hoping through massive asset purchases to alter the supplies and demands for assets such as Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. You would think that in an environment in which the primary instrument of monetary policy is useless, the Fed has less, not more, control over long-term rates than it used to.

But somehow many observers seem to have persuaded themselves otherwise, thinking of the current interest rate on a 10-year Treasury bond as if it were a direct policy choice of the Federal Reserve. Among those who take this view, retirees have been mad at Bernanke for making the interest they earn on bonds so low, while many other observers are upset with Bernanke for now raising rates too quickly, threatening the struggling economic recovery.

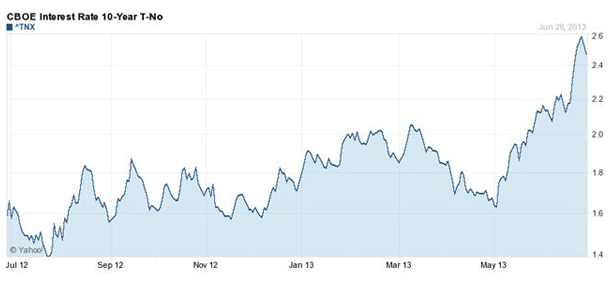

The yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is up 85 basis points from where it had been at the start of May. But only 13 basis points of that rise came on June 19, the day that the Fed released the statement from the latest FOMC meeting and Bernanke held a post-meeting press conference. Of course, just because rates were climbing before the Fed’s statement doesn’t mean the Fed didn’t cause them, as markets are always trying to (and usually do) anticipate the Fed’s moves before they are announced. And the fact that rates continued to rise another 27 basis points in the week after the Fed’s statement also doesn’t mean that the hikes weren’t caused by the Fed. Sometimes it takes a while for analysts to digest what’s been reported and figure out what it really means.

Interest rate on 10-year Treasury security inferred from CBOE TNX, July 2012 through June 21, 2013. Source: Yahoo Finance.

But as I argued last week, it’s hard to see how the Fed’s statements on June 19 changed anything, even (and especially) if you had anticipated them verbatim 6 weeks before they occurred. The accurate message from those statements is that while the Fed is eventually going to stop its large-scale purchases, even slowing down the rate of purchase is still quite a bit down the road. That’s what a reasonable observer should have believed before June 19, and it’s what a reasonable observer should still believe today.

It’s also worth noting that the interbank loan rate in China has been climbing since May. Although the dramatic spike in Chinese rates came immediately after (and appeared to be caused by) the Fed’s statement on June 19, an earlier spike had hit Chinese banks in the second week of June.

Overnight Shanghai interbank offer rate, Jan 4 to June 28, 2013. Data source: Shibor.org.

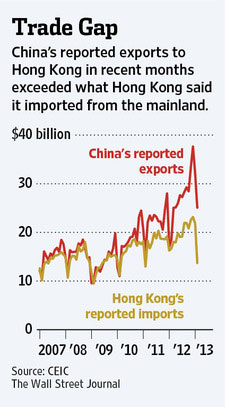

Some remarkable investigating by Izabella Kaminska documented that one important source of short-term funding within China had resulted from over-invoicing of exports, with loans extended for goods that never shipped. Evidence of this can be seen in an explosion of goods that Chinese companies claimed they had shipped to Hong Kong that are not matched by imports that entities in Hong Kong claim to have received.

Source: WSJ.

Business Week reported last May:

Slower growth in last month’s official trade data may reflect measures announced by China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAOFEZ) to crack down on speculative funds entering the country disguised as payments for trade.

The currency regulator said May 6 that it will send out warning notices to companies whose goods and capital flows don’t match as well as those bringing large amounts of cash into China. SAFE on May 22 told banks to improve checks of customer documents related to special trade zones amid speculation that the areas have been exploited to mask money inflows as exports.

The withdrawal of an important funding source would have created a sudden tightening of credit. One manifestation would be the interbank lending rate displayed in the first figure above. Another could be Chinese sales of other assets such as U.S. Treasury securities.

And broader asset sales outside the United States could be a more important development than anything that was said or not said by Ben Bernanke.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply