There’s been ample excellent coverage of the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Shelby County vs. Holder, which declared a key section of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional. By rejecting the VRA’s formula for determining which states and jurisdictions are subject to pre-clearance of changes to their voting laws, the Court effectively derailed the Act’s pre-clearance regime for preventing discriminatory voting practices. (See for example Rick Hasen’s analysis thoughtful here.) Much of the coverage notes the overwhelming bipartisan coalition that supported the VRA’s last renewal in 2006. Reauthorization of the VRA took place ahead of schedule, passed by a House vote of 390-33 and a Senate vote of 98-0, with George W. Bush signing the bill into law days after making his first address as president to the NAACP.

I think the notion of bipartisan support for the VRA in 2006 deserves a bit more scrutiny. First, it seems anomalous, given the rise in partisan polarization over the course of the Bush administration. Second, bipartisanship in 2006 contrasts sharply with the prevailing view in the wake of Shelby that today’s polarization will likely prevent Congress from responding to the Court’s invitation to revamp the Section 4 formula. How can we have such strong bipartisanship on a polarized matter in 2006 and yet no path forward for reform less than a decade later?

A few (admittedly) preliminary considerations:

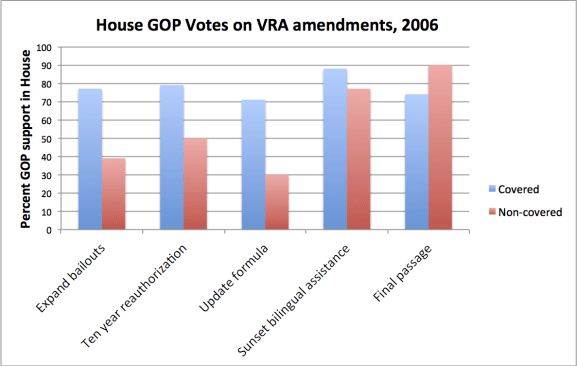

First, reports of strong bipartisan support in Congress in 2006 belie an intense conservative Republican opposition to the basic tenets of the VRA. The bill was brought to the floor only after conservative GOP had derailed the first rule for the bill in June of 2006 on the grounds that the process precluded controversial floor amendments that would have scaled back the provisions of the VRA. (James Tucker details the rebellion here.) Majority Leader John Boehner brought the bill back after acceding to rank and file demands for votes on amendments deemed important to a majority of the GOP majority. Three of the four weakening amendments (which Democrats argued would gut the VRA) secured the support of a majority of the GOP conference, but none of the four amendments passed. The fourth amendment would have re-written the formula to use more recent voting statistics. The figure below shows the percentage of GOP from covered and non-covered jurisdictions voting in favor of the amendments and final passage.

Not surprisingly, amendments’ supporters were largely GOP from districts covered by the Section 4 formula. GOP not representing covered districts were less enthusiastic about undermining the VRA, particularly when voting on an alternative formula. In some ways, the VRA’s bipartisanship was made possible by the structure of the VRA pre-clearance regime: Only one-third of the GOP were immediately affected by the VRA. And GOP from districts not covered by the VRA often benefited from the practice of drawing majority-minority districts that left their own districts with more white voters than they would have had absent the VRA. Coupled with Republicans’ electoral incentives in the mid-2000s to reach out to minority voters, the degree of bipartisanship sustaining the VRA was in large part strategic. That strategic element is also visible in the votes of GOP lawmakers on final passage: After failing to amend the VRA to their liking, over seventy percent of the members from covered districts still voted in favor of final passage.

Why do these 2006 patterns matter? First, we should be wary of overestimating GOP enthusiasm for the VRA in 2006. True, Justice Scalia contended during oral argument that no sane politician would want to be on the wrong side of a bill that references “voting rights.” But deep pockets of more conservative GOP weren’t shy about going on record in favor of a sharply different VRA. Second, the 2006 patterns have implications for the likelihood that the current Congress can restore the VRA. Consider the following:

- Most observers are skeptical that Congress will agree to a new formula. That skepticism might seem at odds with the notion that few lawmakers as recently as 2006 wanted to be on the wrong side of protecting minority voting rights. But partisanship on the House floor in 2006 suggests the opposite: The seeds of partisan polarization over the future of the VRA were already evident seven years ago.

- The seeds of Senate GOP opposition were also evident in 2006. The day before the president signed the bill into law, Judiciary Committee Republicans filed a revised committee report, a statement Democrats claimed spelled out a path for the Court to challenge the constitutionality of the VRA. (Nathaniel Persily offers a very careful review of the 2006 events and their implications here.) Moreover, my hunch is that Senate Republicans in 2006 (led by moderate Republican Arlen Specter) faced more pressure as the Senate majority to carry the president’s water in reauthorizing the VRA than they would today as the Senate minority to support VRA renewal. The majority party is more likely to be blamed for failure to govern than a minority party would be blamed for filibustering the VRA.

- The Court’s hollowing out of the VRA this week has essentially legitimized Republicans’ long-brewing opposition to the VRA’s pre-clearance regime (even if the 5-4 decision cleanly divided Republican and Democratic appointed justices). Even though the number of GOP House members representing previously covered districts remains a small percentage of the House GOP conference, my hunch is that the Court’s decision makes it electorally safer for Republicans not affected by the VRA to break from the bipartisan consensus on the Act. The Court’s decision might in fact unleash conservative groups on the right to more aggressively seek to block GOP lawmakers from returning to the bipartisan fold on the VRA.

To be sure, not all Republicans oppose redressing the gaping hole in the VRA. No less than Majority leader Eric Cantor noted this week that “I’m hopeful Congress will put politics aside, as we did on that trip [to Selma with Democrat John Lewis of Georgia], and find a reasonable path forward that ensures that the sacred obligation of voting in this country remains protected.” Of course, it’s one thing to declare a principled position and quite another thing to corral a recalcitrant GOP conference into bipartisan agreement. But Cantor’s sentiment suggests that at least some Republicans might retain—for strategic or principled reasons—a commitment to exploring ways of recovering the core of the nation’s voting rights regime.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply