We are heading into a big data week, beginning with ISM and culminating with the employment report for May. As I believe the Fed is seriously looking at September to pull back on QE, I will be looking for data that pushes that timing off to December. The employment report is the most important release of course, not just for what nonfarm payrolls tell us about “stronger and sustainable,” but also the unemployment rate. The latter is the specific concern of the threshold condition for reviewing the stance of interest rates, but it is also a concern for the pace of asset purchases. The faster we are moving toward 6.5%, the sooner policymakers will want to pull the plug on QE.

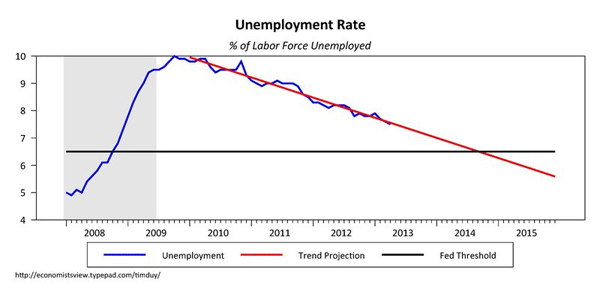

Consider the path of unemployment:

Unemployment is declining at a very steady pace, and at that pace will hit the 6.5% threshold in September of 2014. To be sure, past performance is no guarantee of future performance. We may see, for example, the long-awaiting return to rising labor force participation rates. But we could also see an acceleration in job growth, perhaps sufficient to more than offset any increase in labor force participation, and thus the unemployment rate falls faster than anticipated. A safe bet, however, is more of the same steady decline in rates that we have seen since 2010.

The Fed, I suspect, wants to conclude asset purchases well before they hit the 6.5% threshold and have to make a decision about interest rates. At least three months, but they would probably error on the side of caution and shoot for six months out. That suggests they would like to wind down quantitative easing by March of 2014. Assume further that they do not want to go cold turkey, but rather reduce the pace of purchases across multiple meetings, maybe slowly at first, but more quickly later. So you need about 6 months, or 4 meetings, to wind down asset purchases. That pretty much pushes you back to the September meeting of this year.

To be sure, everything is data dependent. But my point is that the calendar is probably a driving force in timing the end of QE. Just estimate when the unemployment rate will hit 6.5%, work backwards, and it becomes evident why so many Fed officials appear to be leaning toward ending quantitative easing sooner rather than later.

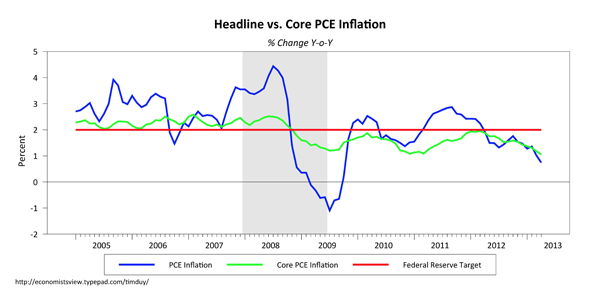

But, you wisely say, but what about inflation? Because inflation is clearly not a problem – or, more specifically, high inflation is not a problem. Arguably low inflation is a problem:

Clearly trending down and away from the Fed’s definition of price stability, or 2% inflation. Smoking gun, you say. The Fed can’t think about backing off QE with inflation trending down.

Perhaps. But let me offer another interpretation. Consider the claim that the failure of inflation to fall further was taken by some as evidence that the economy was near potential output, and that much of the unemployment was structural. The counterargument was that downward nominal wage rigidities keep a floor on wage gains, and thus there is a floor on inflation as well. Thus, the failure of inflation to fall even further, or tip into deflation, tells us little about structural unemployment.

Indeed, the fact that inflation has fallen even as unemployment rates come down is further evidence that structural unemployment was limited. Score one for the importance of downward nominal wage rigidities.

But now those rigidities become a double-edged sword. Policymakers can be relatively confident that deflation will not emerge even when the economy is faced with substantially unemployment gap. Consequently, there is very little chance of deflation, inflation expectations are thus well-anchored, and there is no reason that low inflation should dissuade the Fed from slowing the pace of asset purchases as long as we continue to see “stronger and sustainable” improvement in labor markets.

By extension, policymakers will have an asymmetric response to inflation because they see a lower bound on the downside, but no such bound on the upside. But we can come back to that when rising inflation is a problem.

But what if inflation falls even further? There must be some non-negative rates that prompts additional easing, or, at a minimum, a halt to efforts to reduce asset purchases? Yes, one would be rational to believe that the Fed pushes any policy shift back to December if inflation continues to decline. That said, however, I think you are also still in the world of costs and benefits, and here I will hazard another another conjecture: If I was an monetary policymaker, and I were to look at some of the crazy volatility in Japan, I might reasonably conclude that yes, there may be a point where the destabilizing impacts outweigh the benefits. And the benefits to further action may be very limited considering that the steady decline in the unemployment rate suggests that monetary policy can put a floor under the economy, but may not be able to further lift the pace of activity.

Bottom Line: As always, the data will drive the Fed’s next move. My expectation is that data evolves in such a way that policy will shift in September. I think there is currently a bias toward ending QE, so I anticipate a willingness of policymakers to focus on stronger numbers and downplay the importance of weaker numbers. In other words, I think we need to see some reasonably big downside misses to push policy back to December or later. Policymakers will be watching the unemployment rate, realizing that it has steadily declined despite a number of negative shocks since the recession ended. Expectations of continued declines help focus policymakers on winding down by the end of this year or early next year. If they want to meet that goal while not cutting asset purchases abruptly, then they will need to begin sooner than later. Hence why September comes into focus.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply