Nick Rowe likes to remind us that money is the only asset on every market. If the supply of or demand for this one asset is disrupted then every market will be affected. This reasoning implies that monetary disequilibrium is essential for the emergence of general gluts. This crisis has reinforced this understanding, but also has shed some new light on what it means. Specifically, this crisis has shown that what is used as money is far broader than the standard measures of money. The widely used M2, for example, is limited to retail money assets like cash and deposits accounts that are used by households and small businesses. Institutional investors also need assets that facilitate transactions, but the assets in M2 are inadequate for them given the size and scope of their transactions. Consequently, institutional investors have found ways to make assets like treasuries, commercial paper, repos, GSEs and other safe assets serve as their money. These institutional money assets, therefore, should also be considered part of the money supply. When viewed from this broader perspective, the money supply has been depressed during the crisis in both the United States and the Eurozone. It should be no surprise then that both regions are in slumps.

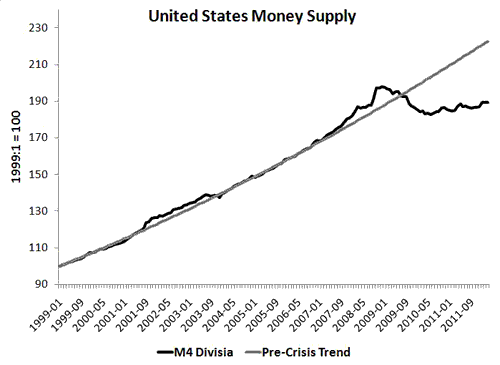

Here are some attempts to measure these broader notions of money. First, from the Center for Financial Stability is the M4 Divisia money supply measure for the United States:

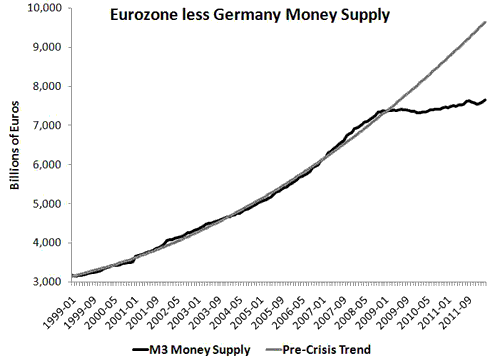

No monetary recovery yet in the United States. What about the Eurozone? Let us first look at the Eurozone less Germany. For this region we use the ECB’s M3 simple sum aggregate. This is not quite as broad as M4, but it does include some institutional money assets:

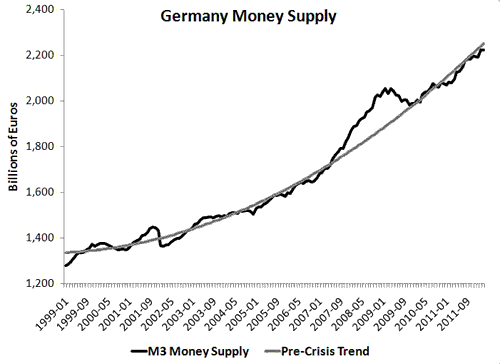

Here too there is a wide gap between the trend and actual money stock. Finally, here is the same M3 measure for Germany:

No surprise here. Germany’s economy is doing relatively well and thus we would expect to see better monetary conditions there. This relative stability of the money stock is another reason why Germany is no rush to open the ECB monetary spigot to save the Eurozone. Why disrupt stable monetary conditions in Germany?

So what are the monetary policy implications? The most obvious one is that the Fed and ECB should create an environment conducive to monetary asset creation that would support the return of robust aggregate nominal spending. Since most of the money assets are created by the credit, maturity, and liquidity transformation services of financial firms, policymakers should aim to create an environment conducive to increased financial intermediation. The easiest way for monetary policy to do this is to raise the expected growth path of aggregate nominal expenditures. This would raise expected nominal income growth and the demand for money assets. This, in turn, would catalyze financial intermediation and lead to the creation of more money assets. And of course, the way to raise the expected growth path of aggregate nominal expenditures is to adopt a nominal GDP level target. It is time for monetary regime change!

P.S. Peter Ireland and Michael Belognia have an interesting new paper that shows money still matters for monetary policy. This is bound to get some New Keynesians worked up! From their abstract:

Over the last twenty-five years, a set of influential studies has placed interest rates at the heart of analyses that interpret and evaluate monetary policies. In light of this work, the Federal Reserve’s recent policy of “quantitative easing,” with its goal of affecting the supply of liquid assets, appears as a radical break from standard practice. Superlative (Divisia) measures of money, however, often help in forecasting movements in key macroeconomic variables, and the statistical fit of a structural vector autoregression deteriorates significantly if such measures of money are excluded when identifying monetary policy shocks. These results cast doubt on the adequacy of conventional models that focus on interest rates alone. They also highlight that all monetary disturbances have an important “quantitative” component, which is captured by movements in a properly measured monetary aggregate.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply