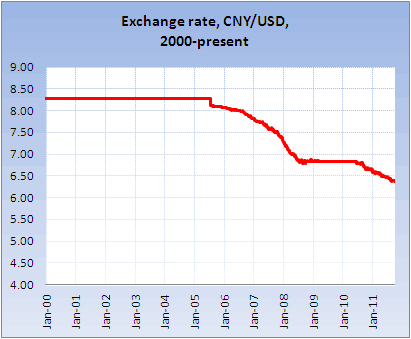

You’ve probably heard that this week the US Congress has been addressing the issue of how China controls its exchange rate with the US dollar. In particular, many have argued that China’s policy of only allowing the yuan (CNY) to appreciate very gradually against the dollar has kept Chinese products unreasonably cheap to American consumers, and American products unreasonably expensive to Chinese consumers. (See for example Paul Krugman’s column on Monday.)

So this week the US Senate voted to consider a bill that would impose tariffs on countries that are judged to have misaligned exchange rates. China has reacted by threatening a trade war, i.e. by threatening to retaliate with its own tariffs. And now Boehner and other Republicans in Washington seem to be ready to stop this bill, so it’s unclear to me whether it actually has a realistic chance of becoming law.

But this is an issue that is not going away any time soon, so it bears thinking about. In general I tend to focus much more on the economics than the legal aspects of international trade and financial issues, but in this case the legal implications could have some important economic effects that we need to consider.

The WTO

The first thing to recognize is that the WTO has a substantial amount of jurisdiction over the tariffs that the US can impose. Why is that? Think of the WTO as a club. Like all clubs, it has certain rules that members must adhere to, and in exchange the members get certain benefits. For the WTO, the primary benefit is that all other members of the club must be nice to you when it comes to trade, meaning that they can not arbitrarily impose tariffs on your products. On the flip side, the rules of the club (naturally) include a prohibition against arbitrarily imposing tariffs on your fellow club members.

So if the US unilaterally imposes tariffs on China, then the US may be breaking club rules. This would mean that the injured party (in this case China) would probably receive official WTO sanction to retaliate. And that is exactly what China has promised to do.

Such a ‘trade war’ (I’ve seen the term in the business press a lot this week) could possibly have some negative implications for the US economy. But it’s hard to quantify how much China’s retaliation would hurt the US, because I suspect that it would be much more informal than formal. For example, I would guess that China will start selecting Airbus over Boeing airplanes for a while. US multinationals could be shut out of lucrative joint ventures in China. And it wouldn’t surprise me if China takes a bit of a breather on trying to enforce copyrights and patents owned by US companies. In addition, China might impose some tariffs on US products, but those would almost be secondary to the informal measures that China could take.

None of these steps would be disastrous to the US, but they might be enough to undo some of the benefit that the US could gain through a stronger CNY. Of course, the US could complain to the WTO about any informal retaliation — the WTO would only sanction formal, tariff-based retaliation. But if the US has unilaterally imposed tariffs on China itself and been found to be in violation of WTO rules, it will not be in a particularly good position (legal or moral) to act as the injured party.

Options

Given this, what are the US’s options for retaliating against China’s weak-CNY policy?

1. Ignore the WTO. First of all, the US could simply go ahead and break the club’s rules, allow the WTO to sanction retaliation by China, and take a chance that China either can’t or won’t punish the US severely enough to make a difference. There are plenty of cases where the WTO has determined that a member has violated the rules, sanctioned retaliation, and the violator has just ignored or put up with the consequences. It’s arguably not very good for the health of the club, but it’s an option.

Note that this is effectively what the legislation currently being considered by the US Congress would do – it would unilaterally impose tariffs on China without trying to get official WTO sanction. And while I’m not entirely clear on all of the reasons for Republican opposition to the bill, this does seem to be one of their concerns; Orrin Hatch has proposed an amendment that would have the US work with the WTO rather than take unilateral action. (Of course, this does then raise the question of why Republicans, who generally despise most international institutions, are more interested than Democrats in respecting them on this issue…)

2. Use the IMF. Another option would be for the US to try to get the IMF on its side. The IMF (another club, with different membership rules and benefits that relate to financial matters rather than tariffs and trade) has rules that specifically prohibit its members from manipulating currencies to gain unfair competitive advantage. And it doesn’t hurt that voting shares in the IMF, unlike with the WTO, depend on how much money each country contributes. Needless to say, this means that the US has a lot more influence there.

The problem is that the IMF rules don’t contain any enforcement or retaliation mechanism. So tariffs by the US would not be sanctioned by the IMF even if the US argues that China is breaking IMF rules.

3. Work the System. But what if the US can make the argument that China is actually the party that first violated WTO rules, so that the US’s tariffs are actually a justified retaliation? Then the WTO would have to sanction the US’s tariffs, and China would be breaking the club rules if it tried to retaliate. Everything would be flipped on its head.

As part of this strategy, the US could cite IMF rules, along with reference to an agreement that the IMF and WTO have signed in which they promised to help each other, respect each other, and coordinate as much as possible. With that legal foundation the US could, through the WTO’s adjudication process, ask the WTO to sanction tariffs on China. If the US wins the adjudication then China must allow its currency to appreciate or face retaliatory US tariffs — which China would then be disallowed from retaliating against. But if China wins the adjudication, then the US must go back to option #1. The primary disadvantage of this strategy, however, is that it’s very, very slow; even if the process started today, it would probably take a year or more before a decision was made. That’s a long time to wait if you think that this policy is important to helping the US out of its current economic slump.

What About the Economics?

I realize that I haven’t yet provided any insight here into what I think should happen from an economic perspective. The short answer on that is that I do think that international clubs like the IMF and WTO serve very useful functions, and that the US generally should avoid undermining them whenever possible. It’s really in the US’s own long-term interest for those institutions to be robust and respected.

But the China issue is a real one. I’m doubtful that a stronger CNY would make a noticeable difference to the US economy over the next year or two — I think the trade effects of exchange rate movements are simply too slow for that — but there’s pretty convincing evidence (see Menzie Chinn, for example) that it would slowly push things in the right direction. So while we shouldn’t think that a different CNY/USD exchange rate would suddenly pull the US out of its economic slump, it might help a bit over time. And that’s worth something.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply