Last week 565,000 people filed first time jobless claims. Although this is the smallest number since January 2009, it is hardly cause for celebration. The unemployment claims data is highly volatile, and numbers reported during holiday weeks are especially poor indicators of employment trends. More telling is the number of continuing unemployment claims, which hit yet another record high of 6,883,000.

While many economists think that the economy is experiencing a labor market shock which will correct sooner or later, data on the duration of unemployment paints a different picture. Problems with the labor market have been brewing for decades.

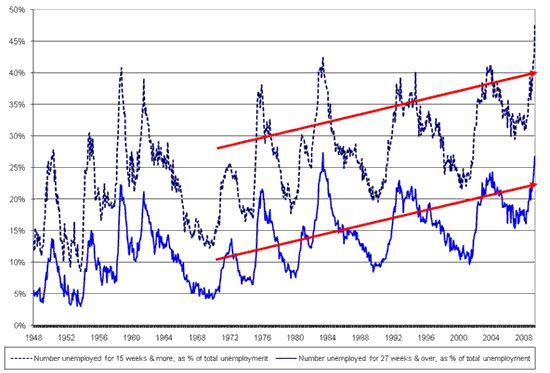

Figure 1 shows the number of people who have been unemployed for 15 weeks or longer as a percentage of total unemployment, as well as those who have been without a job for 27 weeks or more (a subset of the first group).

Figure 1. Duration of Unemployment: Unemployed individuals for 15 weeks or more and 27 weeks or more as a percentage of total unemployment.

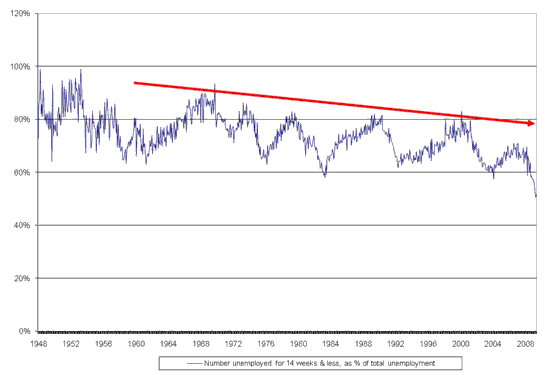

While the series are highly cyclical, their trends have been decidedly up for the last four decades. By contrast, the share of the unemployed without a job for 14 weeks or less has been trending down during the entire postwar period (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Duration of Unemployment: Individuals unemployed for 14 weeks or less as a percentage of total unemployment.

The data shows that an increasing percentage of those without jobs stay unemployed for longer periods of time, while a falling share experience relatively shorter spells of unemployment.

Is this an agile American economy with dynamic labor markets for the world to envy?

Why are 50% of the unemployed remaining jobless for 15 weeks or more, and more than half of them remaining unemployed for over 27 weeks? Some would argue that unemployment insurance (UI) induces individuals to stay unemployed for the duration of the benefits, but UI alone cannot explain the data. In most states, individuals collect unemployment insurance for 26 weeks or less (although in some cases it can be extended) and the benefits are meager. In New York state, for example, benefits (as of December 2008) ranged from $40 to $405, while in Arizona, the maximum UI was $240/week–hardly a strong incentive for someone to stay unemployed.

While unemployment insurance is an important safety net, long term unemployment is becoming an increasing problem for many. (There is the additional problem of the discouraged individuals who have left the labor force, believing that there are no job prospects after unsuccessfully looking for employment opportunities).

A more fundamental question is this: Why is it that the main safety net we offer those who have been laid off is a program that pays them NOT to work for long periods of time?

How about supplementing unemployment insurance with a public service employment program that offers an above-poverty wage/benefit package to all of the unemployed and marginalized individuals who want to work in the public service sector? In addition to the work component, the program can offer training and education to help participants transition to better paid private sector jobs. Wouldn’t that be a more meaningful safety net? The unemployed need not have gaps in their resumes but could instead participate in public service, get training and education, maintain and upgrade their skills, and have useful work experience to bring to their future employers.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply