Market participants turned their attention away from Washington politics to the actual economy, and didn’t like what they saw. Incoming data has too many hints of recession to leave anyone optimistic about the second half. And while corporate profits have held up despite weak growth, it is difficult to see how they could retain recent gains in an outright recession.

Moreover, the reality of the budget deal is starting to set in. What the economy needed was near-term stimulus and long-term consolidation. What Washington delivered was just consolidation, both near and long-term. Now market participants are scratching their heads around three basic questions: Is recession imminent? How deep would it be? When will Washington come to the rescue?

The story I take away from the data is this: The US economy quickly lost any momentum developed in the back half of 2010 as the impact of higher commodity prices rippled through the economy. To be sure, this was compounded by the impact of the Japanese disruption, but that episode should have had little impact. The disruption was expected to be short-lived, and largely has been.

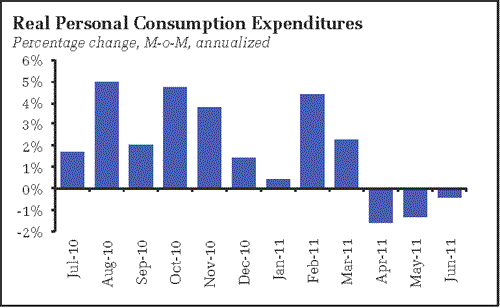

The commodity shock left a deeper mark on the economy. Not only did it directly impact households via higher energy prices, but I sense that firms where eager to try to push through higher prices. I also think one can argue that firms where goaded into higher prices by certain Fed officials who fanned the flames of inflation fears. The combination was that real consumption spending hit a wall:

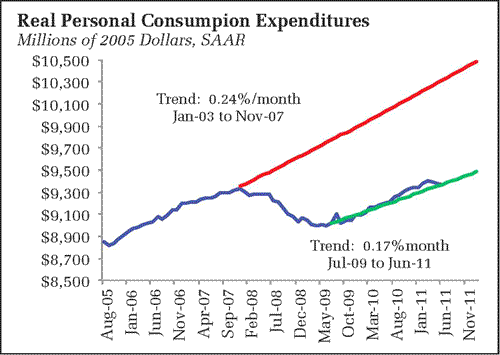

And once again we return to the story of a new normal – not only is consumer spending at a lower trend line, but a lower growth rate as well:

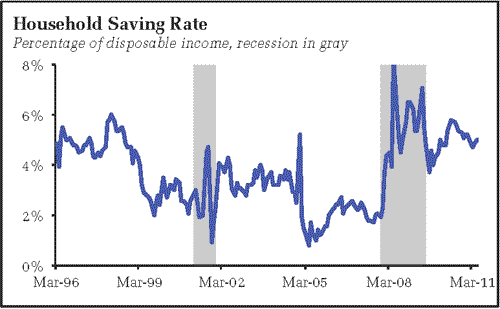

Somewhat surprising to me is that saving rates held up:

I would have expected households to reduce saving to support consumption, but that didn’t happen. Perhaps households are more cautious than before the recession, not willing to push their budgets to the maximum. Perhaps those most affected at the low end of the income scales simply had no room in the budget to begin with. Perhaps households saw the commodity price increase as largely permanent, a rebound from the recession washout. Not a bad bet, either, given that while oil prices are off their highs, black gold still isn’t cheap. All these explanations are bad news for the Obama Administration, whose release of the SPR was obviously an effort to goose real spending over the next four quarters with an eye toward the 2012 election. I am hoping they are looking for plan B. Or plan C actually, as the debt reduction deal didn’t exactly bring out the confidence fairies.

Indeed, the opposite seems to have happened. The uncertainty surrounding the debt ceiling appears to have had real effects on the economy as firms and individuals turned cautious. That’s a story I see in the ISM data. New orders dropped off, while so too did inventories – firms appeared to have tightened down on inventories, wary of an impending budget disaster, and cut orders. The optimistic side to this story is that now that the debt ceiling has been raised, firms will boost orders to make up for lost ground. The pessimistic side is that now firms know the magnitude of the fiscal drag, and will cut orders accordingly. We just don’t know which story will dominate yet. Once the giant ship of the US economy is turned into choppy waters, how quickly can it be turned back?

For what it’s worth, auto sales where up in July, setting the stage for stronger growth in the second half. Thin rope to hold onto, I know. But one inconsistent with recession, arguing instead for a “growth recession,” ongoing tepid growth rates.

This is where the first question bleeds into the second. What kind of recession would we expect? Mild or severe? I think that fears of a deep recession should be highest when the economy is operating at high capacity and/or when significant imbalances have developed. Obviously, in the current environment, the economy is operating at low capacity, with only limited recovery since the recession ended. Difficult to see, for instance, a drop in new housing starts of the magnitude seen in recent years. Impossible, really, given the downside limit. One has to imagine something similar holds true for auto sales. And bank lending. And households are already in the process of deleveraging.

You get the idea. I think combining my thoughts on the first and second questions yields a high probability of slow growth, but a lower (20-30%) probability of mild recession, and a very low probability of severe recession. I was concerned that government spending would come to a standstill, which would certainly plunge the economy into recession, but luckily that fear was not realized.

Still, all of those outcomes are bad, in my opinion. Just varying degrees of bad.

The final wild card is the European debt crisis, which continues to smolder (blaze?) while European leaders head off for vacation. I guess you need to maintain your priorities. Typically, the impact of external shocks on the US economy is limited. But here we have the potential for a collapse of the Euro area economy as we know it. Once has to imagine that is an “all bets are off” situation. In any event, given the weakened, fragile state of the US economy, even a mild negative shock could have significant ramifications.

Will Washington come to the rescue? I think we should see some increasingly dovish talk from Federal Reserve officials in the weeks ahead, especially if the next jobs report is as lackluster as the last two. That said, the inflation outlook is likely more important than the growth outlook in the evolution of Fed policy. Minneapolis Federal Reserve President Narayan Kocherlakota via the Wall Street Journal:

Writing in his bank’s annual report, the central banker said: “I will be paying close attention to the behavior of core inflation” as he thinks about the ideal setting for monetary policy. Changes in inflation stripped of food and energy factors appear “to provide critical information” about the state of labor markets and other factors, “and therefore about the appropriate stance of monetary policy.”

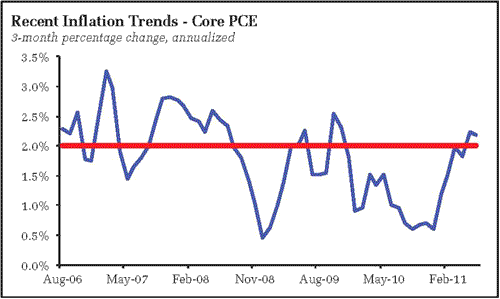

I think it is clear that a significant portion of the Fed’s hesitancy to add more stimulus stems from recent inflation gains:

As important, or perhaps even more so, is the rebound in market-based measures of inflation expectations. Today the 10 year TIPS traded with a yield of 35bp, while the standard 10 year equivalent traded at 262bp, an implied inflation spread of 227bp, well above the lows of last August. Apparently market participants expect very low real growth over the next 10 years while anticipating the Fed will successfully keep inflation near is target. My sense is that more FOMC members than not concur – there is little they can do about growth, but they can act to prevent deflation. And they will. The growth outlook just needs to deteriorate such that the inflation outlook ease as well. We just aren’t there yet. And remember, they will likely put more weight on upside surprises than downside dissapointments as they look for reasons not to do more. Something to keep in mind as employment day approaches.

As for fiscal policy, all I can say is that we repeatedly get less of it than we need. I don’t see that changing anytime soon. Team Obama appears to think they have done all they can to support the economy. Moreover, they don’t see the need for concern:

President Barack Obama’s spokesman is discounting talk that the economy may be headed back into recession, despite recent concerns of economists.

Spokesman Jay Carney says there is no question that economic growth and job creation have slowed over the past half year.

But, Carney told a White House briefing, “We do not believe that there is a threat of a double-dip recession.”

Perhaps by the time we get to December we will wonder what all the fuss was about. Still, as Krugman noted, hope is not a plan.

Bottom Line: This recovery continues to be anything but fun. The US economy shifts gears every six months, overall showing little promise that it can sustain the kind of momentum necessary to rapidly alleviate labor market pain. More dovish monetary policymakers are likely starting to see room for more easing, but the hawks likely still rule the roost. We need to see real deflation fear reemerge to shift policy gears. Fiscal policy looks set to go nowhere as far as stimulus is concerned; I still hope we can look forward to more than an extension of payroll tax relief, but I am not holding my breath.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply