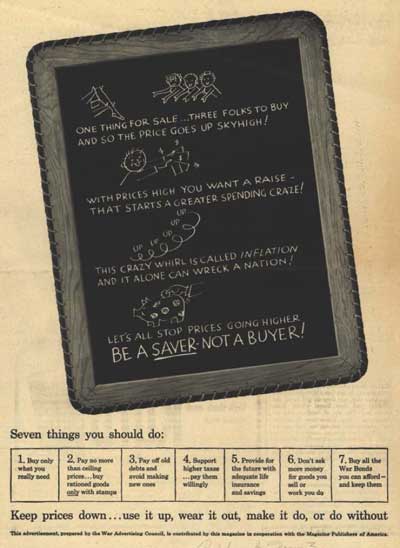

During World War II, advertisements warning against inflationary behavior were common. One example:

This is a simple description of a wage-price spiral, something that was a real threat at the time as massive resources were being directed at the war effort. Some members of the Federal Reserve appear to believe this threat is as real today as it was then. Mark Thoma directs us to the Wall Street Journal, where Kathleen Madigan reads the FOMC minutes and concludes:

Windfall for commodity producers, no problem. Bigger paychecks for U.S. workers, now wait a minute…

That’s one reading of the minutes from the Federal Reserve‘s April 26-27 Federal Open Market Committee. The strategy makes sense from an economics’ standpoint; but it carries risks on both the political and growth fronts.

The extreme end of these fears can be found in Kansas City Federal Reserve President Thomas Hoenig’s recent Washington Post interview:

WP: One place where there’s not any inflation is in wages. Can you really have an inflation problem without wages rising?

TH: Not initially. But people are losing real purchasing power, and that changes how they’re going to negotiate. People want this lost purchasing power back in time. In negotiating, they’ll say, “Prices have been rising, we deserve more.” We’re already seeing it in some of the surveys that we run. Businesses are telling us, “Yes, we had a pay freeze a year and a half ago, but we’re doing some catch up now. We want to make sure we keep our good people.”

Any significant wage gains in the current environment appear to be sector specific – it certainly does not appear in the aggregate data. And note Hoenig’s distress that some firms are looking to play catch-up. I think you could interpret this as Hoenig desiring to see a downward level shift in trend wages. In other words, Hoenig expects the recession should result in a permanently lower level of standard of living than would have been the case otherwise.

For the moment, however, calmer minds prevail, pushing the Fed to delay tightening. From the minutes:

In their discussion of monetary policy, some participants expressed the view that in the context of increased inflation risks and roughly balanced risks to economic growth, the Committee would need to be prepared to begin taking steps toward less-accommodative policy. A few of these participants thought that economic conditions might warrant action to raise the federal funds rate target or to sell assets in the SOMA portfolio later this year, but noted that even with such steps, monetary policy would remain accommodative for some time to come. However, some participants indicated that underlying inflation remained subdued; that longer-term inflation expectations were likely to remain anchored, partly because modest changes in labor costs would constrain inflation trends; and that given the downside risks to economic growth, an early exit could unnecessarily damp the ongoing economic recovery.

If unit labor cost growth remains constrained, the Fed will tend to delay tightening, as the overriding economic reality is that simply described by New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley:

…the recovery remains moderate and we still have a considerable way to go to meet the Fed’s dual mandate of full employment and price stability.

That said, it is worth considering that even the Fed doves probably have something of an itchy trigger finger when it comes to tightening. They are willing to stay the course given the lack of pass-through to wages, but one could imagine that changing quickly with the slightest whiff of rising unit labor costs. Which brings to mind an interesting topic. Way back in 2009, spencer at Angry Bear noted that labor payments as a share of output have been falling since the early 1980’s. Can this situation ever be reversed if the Fed steps on the brakes every time workers get a little too confident for their own good?

Mark concludes his review of the Madigan piece with:

We are much too worried about a wage-price inflation cycle breaking out and causing problems. If the Fed is too trigger happy, it could snuff out the recovery it is hoping to bring about.

The Fed is much, much better at slowing the economy down than it is at speeding it up. Thus, if the Feds is going to make an error, it should be biased toward the error it can fix the easiest. That is, in the face of uncertainty the Fed should be biased toward policy that is too loose rather than policy that is too tight — a policy that is too loose is easier to correct if it’s wrong. Unfortunately, I don’t think the Fed sees it this way.

No, the Fed doesn’t see it this way. I think I know exactly how the Fed would respond to Mark: You think the 1980’s were easy? The expansion of the balance sheet has given rise to too many fears of the 1970’s within the Fed, and those fears will drive the Fed to try to stay far ahead of the inflation curve. That argues for a premature tightening. This year? Still seems difficult to imagine given the state of the economy. But next year seems reasonable, as further strengthening of the labor market will enhance fears that inflationary wage gains are just around the corner.

Finally, for those in Congress chastising the Fed for inflation, note point 4 in the advertisement above:

Support higher taxes…pay them willingly.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply