Fresh Air had an excellent interview with Georgetown law professor Adam Levitin, who blogs here. It’s only 21 minutes and I recommend it if you are interested in credit cards or in financial regulation in general.

Credit cards are an interesting if perhaps extreme case of the interplay between “innovation” and regulation in the financial industry. A long time ago, someone invented the credit card. This was a real, beneficial innovation, because it allowed people to make medium-sized purchases on credit. (You could already buy a house on credit, if you put 30% down.) Let’s say that without credit, it would take you nine months to save enough money to buy a refrigerator. Now you could buy the refrigerator and then save the money; it might take you ten months with the interest, but you get to use the refrigerator for that whole time. (A refrigerator could also save you money, because it might allow you to go shopping less often, buy in bulk, and eat at home more.) All good so far.

Someone also invented the charge card (like the old American Express card), which gave you the convenience of not having to carry around cash, and the ability to make long-distance purchases immediately, rather than having to mail a check and wait for it to clear. Also a good thing. All credit cards have this feature in addition to the credit feature.

Since then, however, Levitin argues that all the innovation in the credit card industry has been in pricing – specifically, making prices less transparent, so issuers can “compete” over interest rates while they really make money on fees (late fees, cash advance fees, foreign transaction fees, etc.) and billing practices (like double-cycle billing). The actual product you get – the ability to take out a modest unsecured loan on an instant’s notice – is the same as it always was.

From my personal perspective, credit cards are a lot better than twenty years ago, but that’s because I pay no annual fee and I get rewards (cash back). This is pure reallocation of money, since all that has happened is that the interchange fees charged to merchants are now going to fund my rewards, and those interchange fees get passed on to consumers as higher prices. More generally, Levitin says, the innovation has gone into more and more complex combinations of different price terms (teaser rate, long-term rate, ability to change rates, late fee, reward program, etc.) that simply make it harder for consumers to understand what they are paying.

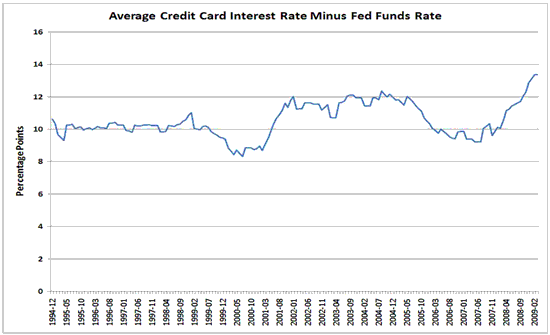

If innovation doesn’t give us new products, does it at least give us the same product at a lower price? Not so much. Here is a graph of credit card interest rate spreads (interest rate minus Fed funds rate) since the end of 1994:

Data are from the Federal Reserve; credit card rates are from Table G.19, credit card rates on accounts assessed interest; Fed funds rates are from Table H.15. Since credit card rates are only available quarterly, I used a 3-month trailing average of both series. That spike at the end is not particularly ominous, at least not yet; the Fed funds rate has collapsed over the last two years, and credit card rates haven’t had time to catch up.

Given this situation, Levitin argues that the usual approaches to regulation are ineffective. Disclosure alone is insufficient when consumers lack the ability to estimate the total cost of credit based on complex interest rate and fee schedules. (I would add that disclosure also doesn’t work when people have biased estimates of their own future behavior – as in, “I’m not going to miss any payments.”) Prohibiting specific practices, as in the recent credit card bill, only motivates card issuers to find new things to charge money for.

Instead, he says, regulation should constrain the number of things issuers can charge money for – like the interest rate, the annual fee, and the transaction fee – and then let them compete on price. The basic product will be the same, since it’s never changed. And there will be no caps on prices or fees, so even risky borrowers will be able to get credit at some price. The main difference is that people will have a clear understanding of what the price actually is.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply