Unless every able American pitches in, Congress and I cannot do the job. Winning our fight against inflation and waste involves total mobilization of America’s greatest resources—the brains, the skills, and the willpower of the American people.

“Whip Inflation Now” Speech (October 8, 1974)

President Gerald Rudolph Ford

Falling into deflation is not a significant risk for the United States at this time, but that is true in part because the public understands that the Federal Reserve will be vigilant and proactive in addressing significant further disinflation.

“The Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy” Speech (August 27, 2010)

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke

Rereading Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s recent speech and measuring it against the incoming data leaves me with a pit in my stomach. I sense Bernanke reveals in this speech he is the proverbial emperor without clothes, short on policy options but long on hope. A last ditch attempt to persuade us that as long as we don’t believe deflation will be a problem, it will not be a problem. But he faces the same challenge as did then President Gerald Ford. All hat and no cattle. You need to be ready to back up your talk with credible policy options. While Bernanke outlined possible policy options, reading between the lines makes clear he lacks conviction in the viability of any of those options. Simply put, Bernanke is not ready to embrace the paradigm shift bold action requires.

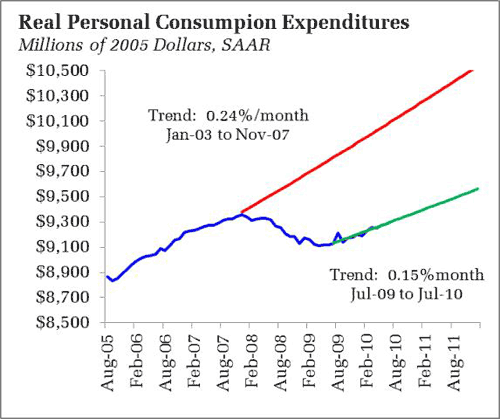

First, it is worth considering the economic context of the policy environment via the lens of July Personal Income and Outlays report. Real gains fells short of what I believe to be already diminished expectations, with a clearly suboptimal trend in place:

When Bernanke expresses concern for the near term pace of economic growth, he is concerned with failing to track the current path of economic activity, that illustrated by the path of consumption since July of last year. This already is a substantial lowering of the bar, and appears to be a resignation that previous trends are unattainable. That is a problem in many respects, the most important of which is that previous trends were consistent with full employment. The failure to acknowledge the importance of re-achieving the previous path is, in my opinion, an admission of the willingness to accept a protracted period of high unemployment. This, of course, as been essentially admitted by Bernanke:

Although output growth should be stronger next year, resource slack and unemployment seem likely to decline only slowly. The prospect of high unemployment for a long period of time remains a central concern of policy. Not only does high unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment, impose heavy costs on the unemployed and their families and on society, but it also poses risks to the sustainability of the recovery itself through its effects on households’ incomes and confidence.

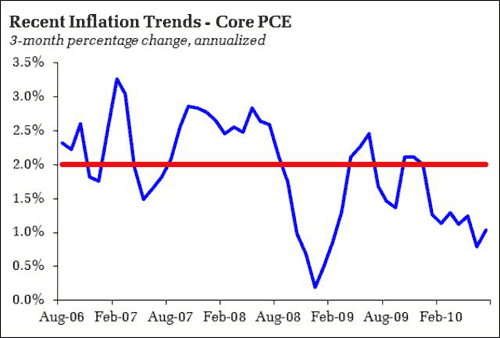

As I have already commented, if unemployment is a concern, and there is no conflict between the Fed’s dual mandate, then why is the Fed waiting for further evidence of disinflation before acting? Indeed, Scott Sumner saw a line in the sand in Bernanke’s speech of a one percent inflation rate. The most recent PCE data suggests we are perilously close to testing that line already:

Unemployment hovering just south of double digits, while near term inflation is hovering around one percent. And if that wasn’t enough, the threat of near term slowing is all too evident. The recent spate of regional surveys suggests the much vaunted manufacturing revival is about to end, with the ISM likely to drop below 50 in the next month or two. The July report on durable goods, which revealed a sharp eight percent drop in new orders for nonair, nondefense capital goods bolsters this prediction. Moreover, Intel sent up another red flag on the sustainability of consumer spending in the back half of this year. And I think we all realize that the government’s efforts to prop up the housing market are falling short of Washington’s expectations.

If short term interest rates were at five percent, or three percent, or even one percent, policymakers would be falling over themselves to ease further. Yet at this point the most we get is a commitment to hold policy steady, and even that grudgingly accepted by some policymakers. Why so little, despite Bernanke’s pleads that he can do more? Because the Fed is now up against the zero bound, and the available options are of uncertain effectiveness and internally contentious.

Consider what is the most likely path Bernanke would choose, the expansion of the balance sheet via additional asset purchases:

I believe that additional purchases of longer-term securities, should the FOMC choose to undertake them, would be effective in further easing financial conditions. However, the expected benefits of additional stimulus from further expanding the Fed’s balance sheet would have to be weighed against potential risks and costs. One risk of further balance sheet expansion arises from the fact that, lacking much experience with this option, we do not have very precise knowledge of the quantitative effect of changes in our holdings on financial conditions. In particular, the impact of securities purchases may depend to some extent on the state of financial markets and the economy; for example, such purchases seem likely to have their largest effects during periods of economic and financial stress, when markets are less liquid and term premiums are unusually high. The possibility that securities purchases would be most effective at times when they are most needed can be viewed as a positive feature of this tool. However, uncertainty about the quantitative effect of securities purchases increases the difficulty of calibrating and communicating policy responses.

Translation: Asset purchases are effective in times of crisis, but otherwise are fraught with uncertainties that limit there policy viability. We simply have no idea how to implement policy via asset purchases. They are a last ditch effort, at best.

Moreover, to be effective, they likely need to be conducted on a massive scale, especially if the Fed sticks with Treasuries as their main course. Former Fed staffer Vincent Reinhart, via NPR:

GHARIB: Now just to bring up the subject of tools, Alan Binder as you know a former vice chair of the Fed, wrote an op-ed piece this week saying that the ammunition that the Fed has to fix the economy, they`re running out and what they do have is the weak stuff. Now, Bernanke disagrees. What do you think?

REINHART: OK, so I think Chairman Bernanke probably disagrees on two main counts. One is there`s still communication. The Fed could convey they`re going to keep interest rates low for a very long time. They`ve probably done as much as they can on that front. They maybe could do a little bit more. But that leads to one other option, which is buying stuff, buying Treasury securities. Now, Alan Binder I think, believes that that effect isn`t that great, but the way you get around that is to buy in very large volume. That`s probably also why the Fed is hesitant to act. It feels that when the time comes to do unconventional policy action, it will have to do very large purchases of Treasury securities.

So, the answer is volume. Interestingly, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard made some comments on that point. From Bloomberg:

The Federal Reserve may increase purchases of Treasuries if the U.S. economy weakens further, though any new program should be “disciplined,” St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard said.

“The committee gave a signal that we are ready to move if conditions deteriorate further, which was certainly in line with my thinking,” Bullard said in an interview on CNBC Television today at the Fed’s annual symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “I want a disciplined program.” …

…“If we could still target interest rates, we would make small moves to adjust to the data,” Bullard said. “I think we should do the same with our quantitative easing program.”

Note: A “disciplined” program with “small moves.” And Bullard is one of the most willing policymakers to pursue additional quantitative easing, yet he offers what is at best a recipe for policy disaster. Small moves are almost certain to yield very small impact, and will only intensify the growing sense that the Fed is at the end of its rope.

Reinhart also mentions of Bernanke’s second option, communication, but also notea the Fed has already exhausted that avenue. Bernanke seems to agree:

A potential drawback of using the FOMC’s post-meeting statement to influence market expectations is that, at least without a more comprehensive framework in place, it may be difficult to convey the Committee’s policy intentions with sufficient precision and conditionality.

Translation: We don’t have a comprehensive framework in place, and we won’t as long as some policymakers believe that the appropriate course of action is to raise interest rates.

Bernanke then dismisses the option of reducing interest on reserves, and gives no ground to Bruce Barlett’s suggestion that the Fed think outside the box and actually charge interest on reserves. The fourth option, that of raising inflation expectations, is simply unthinkable.

In sum, what Bernanke actually said is that yes, there is more that we can do, but really none of it is effective and we do not intend to go there unless things get really, really bad. How bad? Your guess is as good as his:

At this juncture, the Committee has not agreed on specific criteria or triggers for further action…

They haven’t even agreed on current action. Yet we can trust them to counter deflation when they see it. Paul Krugman sees the current situation as a monumental failure of Bernanke to follow his own research:

The sad thing is that policy makers were supposed to know all this. The Fed had studied Japan extensively, and believed that the Bank of Japan could have averted the lost decade if it had reacted very aggressively early on. Larry Summers talked about a Powell doctrine of overwhelming force in the face of crisis. And yet what we actually got was an underpowered response on both the fiscal and the monetary fronts.

As I’ve said before, we — and particularly Summers-san and Bernanke-sama – owe the Japanese an apology.

I think that Bernanke believes that he did in fact follow his own research, and orchestrated what he believed was an overwhelming force. And that force did help bring the crisis to a close, but fell short of what was necessary to revitalize the economy. Now that force has been expended, and they have little left in the arsenal.

The conventional arsenal, that is. I believe the Fed fundamentally views monetary policy as operating via interest rates, and is loathe to break that view, despite being stuck at the zero bound. Bernanke on reducing interest on reserves:

Moreover, such an action could disrupt some key financial markets and institutions. Importantly for the Fed’s purposes, a further reduction in very short-term interest rates could lead short-term money markets such as the federal funds market to become much less liquid, as near-zero returns might induce many participants and market-makers to exit. In normal times the Fed relies heavily on a well-functioning federal funds market to implement monetary policy, so we would want to be careful not to do permanent damage to that market.

Seriously, millions of people looking for work, for years, according to the Fed’s own forecasts, and Bernanke is concerned about permanent damage to the federal funds market? He can’t deal with that problem at full employment?

Finally, note that Bernanke fails to describe what is arguably the most potent weapon remaining. Buy foreign currency. Lots of it. Rather than target interest rates, target a steady, nondiscriminatory depreciation of the Dollar until we can lift rates far from the zero bound. Or target equity prices. Or just put cash in bank accounts. Bernanke thought outside the box when it came to alleviating the crisis on Wall Street. Time to think outside when dealing with Main Street.

Bottom Line: Bernanke’s speech struck me as anything but reassuring. He made it clear that the Fed’s remaining options were weak and/or less than palatable for policymakers. With such low ammunition, how can we take seriously his conviction that the Fed will aggressively defend against the threat of deflation that is already upon us? Simply wait around for the fiscal policy backstop? Don’t hold your breath – this Administration is about to be on the run; they have already dropped the policy ball, and there will not be a second chance. We already had a lost decade, and another is upon us.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply