There’s been a bit of a debate going on in the blogosphere lately about whether the Democrats should have proposed a more limited health reform plan in the first place. Such a plan might have gotten some Republican support or at least led to less intense Republican opposition and both improved the health system and given the Democrats a badly needed victory. The plan they proposed instead was too big to pass, so the thinking goes.

There’s been a bit of a debate going on in the blogosphere lately about whether the Democrats should have proposed a more limited health reform plan in the first place. Such a plan might have gotten some Republican support or at least led to less intense Republican opposition and both improved the health system and given the Democrats a badly needed victory. The plan they proposed instead was too big to pass, so the thinking goes.

As a purely political matter, I think this analysis is wrong. The real problem, in my view, is not that the Democrats’ ambitions were too large, but rather that they were too small. In particular, I think they erred by not making the case for a single-payer system in the first place. Had they done so, the plan they eventually developed would have appeared to have been a modest alternative.

I say this not because I favor a single-payer health system—although I don’t fear such a system particularly, either. Rather, it’s because I understand political dynamics—you often have to ask for twice what you want in politics in order to end up with half of what you need at the end of the day. The great mistake that administrations of both parties often make is to put forward plans that have no bargaining chips or fallback positions built into them. The various trade-offs inherent in any major policy initiative were made within the administration rather than between Congress and the administration. This meant that the administration’s initial proposal was really its bottom line position; it had nothing to negotiate with and once the inevitable compromises started, the logic and integrity of the proposal quickly collapsed.

Also, I think administrations are sometimes unclear in their own minds about what precisely they are trying to accomplish. In terms of health reform, Barack Obama’s main campaign promise was to “bend the curve;” i.e., cut the growth rate of total health spending to a sustainable level. But this cannot be done without abolishing or at least severely scaling-back the tax exclusion for health insurance—a sacred cow only slightly less sacred than the mortgage interest deduction. Unfortunately, John McCain made this the centerpiece of his health reform plan during the campaign. In order to score some cheap political points, Obama opposed it. So when the time came for him to propose a health reform plan of his own, the central element that needed to be there for the plan to reduce costs was off the table.

Without some way of scaling back private health spending through the tax code, the only real alternative is essentially a single-payer system such as they have in virtually every other major country. I think a strong case could have been made for such a system on cost control grounds alone. Yes, this would have meant rationing, but it wouldn’t necessarily have meant that health outcomes would be worse. The people of France, Switzerland and Germany are not less healthy than Americans. (I don’t have space to do a detailed international comparison of health outcomes, but I would note that infant mortality is a pretty basic measure of a national health system’s quality and according to this CDC study practically every major country has significantly lower infant mortality rates than we do.)

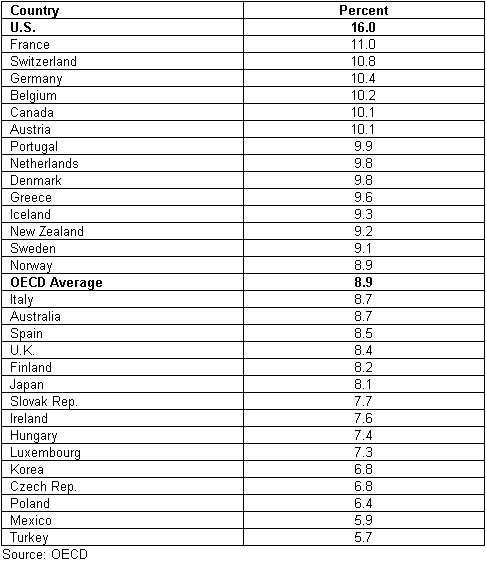

Yet every major country spends very significantly less of its national output on health than we do. As Table 1 shows, we spend five percent of GDP more than the country with the second-highest level of health spending as a share of GDP. Five percent of GDP is about $700 billion that Americans could be spending on new homes, cars and clothing, nice restaurants, paying off bills or anything else they can imagine. Instead, that money went to doctors, hospitals, pharmacists and insurance companies. If we only spent as much as Japan—a country known for having an excellent health system and a healthy population—we would have eight percent of GDP, about $1 trillion, to spend on anything we like.

Table 1. Total Health Expenditures as a Share of GDP, 2007 (latest available)

Of course, many will assume that we can’t afford a single payer system without vastly increasing government spending. What they probably don’t realize is that we are already spending a vast amount on health through government as it is for programs like Medicare and Medicaid. As Table 2 shows, only eight other countries have government spending on health greater than we have, and most of those spend only a trivial amount more.

Table 2. Public Health Expenditures as a Share of GDP, 2007 (latest available)

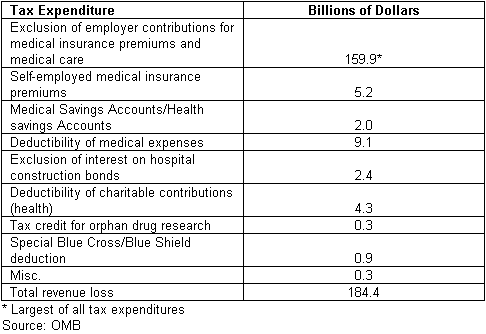

Moreover, I believe these data substantially understate the total amount of health spending that flows through government because I don’t think they account for the revenue loss associated with tax expenditures for health insurance and care. These are very substantial, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Federal Corporate and Individual Tax Expenditures for Health, 2010

If the tax expenditures for health were included in overall health spending, then public expenditures in the U.S. would be at least 1.3 percent of GDP higher and private spending would be concomitantly lower (to avoid double counting). (Keep in mind that to the extent that state and local governments also exempt health expenditures from taxation, the total tax expenditure would be a couple of tenths of GDP higher.) If that were the case, we would be spending as much as France does.**

To wrap up a post that has already gone on much too long, what I am trying to show is that for no more than we are already spending on health through the government we could have a single-payer system no worse that those that exist in almost every other major country. My point is that this is an option that the administration should have at least floated and on which we should have had a national debate. I don’t think Americans would have embraced such an option, but as I said at the beginning it would have clarified the debate by focusing on the overall cost of our health care system—which I believe is far too great for what we get in return—and made reforms such as those that the Democrats have put forward seem modest by comparison. That would have improved their political chances of success.

** I don’t know to what extent other countries also have tax expenditures for health that are not included in the figures for total health spending. However, a new OECD study suggests that they are small or nonexistent. Of seven countries studied (Canada, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands, Spain, the U.K. and U.S.), four had no tax expenditures for health at all and the two others that have them have revenue losses as a share of GDP less than a third of ours. See Tax Expenditures in OECD Countries (Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2010), p. 224.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply