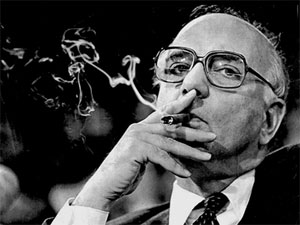

Paul Volcker lays out his argument in the New York Times today for “Volcker rule” — President Obama’s new proposal to rein in “too big to fail” institutions by limiting the size of banks and keeping them out of riskier businesses like proprietary trading, hedge funds and private equity.

Paul Volcker lays out his argument in the New York Times today for “Volcker rule” — President Obama’s new proposal to rein in “too big to fail” institutions by limiting the size of banks and keeping them out of riskier businesses like proprietary trading, hedge funds and private equity.

But those who suspect that the proposal is window-dressing for the more tepid approach favored by Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner won’t get much comfort.

Volcker starts off well, identifying the core problem of protecting institutions considered too big to fail. “Public outrage over seemingly unfair treatment is palpable,” he says. It creates “moral hazard” and it gives the biggest institutions “competitive advantage in their financing, in their size and in their ability to take and absorb risks.” He even invokes Adam Smith, the father of free market theory, as a supporter for keeping banks small.

But then there is this jolt:

That approach does not really seem feasible in today’s world, not given the size of businesses, the substantial investment required in technology and the national and international reach required.

Huh? What about Obama’s idea to limit the size of the banks, based on the size of their liabilities? Even if it was nothing more than a call to limit the biggest banks to their current size, where was that? Nowhere. Volcker simply pivots to the other proposal, on keeping banks out of prop trading.

I became even more suspicious by the way Volcker made only glancing reference to other key initiatives that could reduce TBTF — namely, better capital requirements.

If you really want to rein in moral hazard and risk-taking associated with the implicit government backstop for huge institutions, then your most potent tool is to impose sharply higher capital requirements on the giants. Aligning the risks of size with much bigger capital reserves to offset that risk would be a huge disincentive for institutions to get as big as they possibly can. Structured properly, capital requirements could even induce banks to divest parts of their business before they become too big to fail.

But while there is constant lip service these about tougher capital requirements, it is far from clear that the Obama administration wants to push that hard. And Volcker’s rather off-hand reference isn’t encouraging.

Volcker does make a spirited case for his other key structural proposal: prohibiting banks and bank holding companies from engaging in prop trading. But as the cliche goes, the devil is in the details and Volcker stays far away from any specifics.

Let me stipulate: I think Volcker sincerely wants to make big structural reforms, and he is clearly bolder than most of his colleagues. But it’s much less clear what the Treasury and White House really want to do. Volcker is too polite to rail in public against the White House if he thinks the president isn’t going as far as he himself would like. But that doesn’t mean that doesn’t mean that Obama’s proposed rule is the same as the “Volcker rule.”

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply