All eyes will be on tomorrow’s employment/unemployment report, for good reasons. The relative strength of the report will provide yet more essential information on the likely strength of the still young recovery. But as the expansion continues, questions about long-run trends in labor markets will increasingly dominate thinking about what the nation should expect going forward. One important element in interpreting unemployment data is the trend in labor force participation, and it appears as if there are some significant open questions about what the trend looks like.

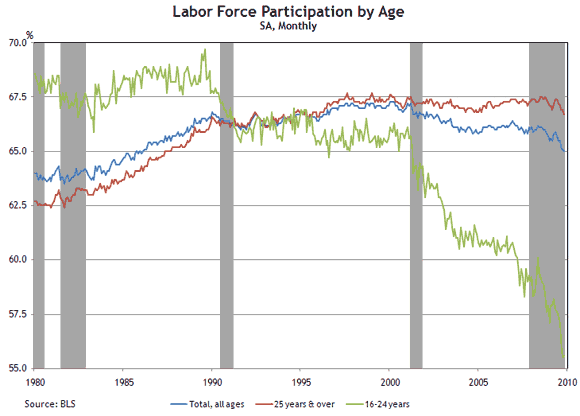

After growing during the 1980s and 1990s, the aggregate labor force participation rate (the percentage of the working-age population active in the labor market employed or looking for work) peaked in the late 1990s and is currently at levels last seen in the 1980s. But this change pales in comparison to changes in labor force participation among America’s youth (those folks in the 16- to 24-year-old age range).

During the 1980s participation in the labor market for youth averaged around 68 percent, a rate noticeably higher than for older individuals. The youth participation rate declined sharply to a level at or below the level for older individuals prior to the 1990–91 recession and then remained relatively stable during the 1990s. However, over the past decade youth labor market participation has been on a steep downward trend and currently stands at a little over 55 percent, compared with about 67 percent for older individuals. Moreover, the most recent recession has seen youth participation rates decline at a rate similar to that seen in the early 2000s. In contrast, the labor force participation by individuals over 24 years of age has varied much less, implying that the decline in youth labor force participation has been a major contributor to the reduction in the overall rate of labor force participation (see the above chart).

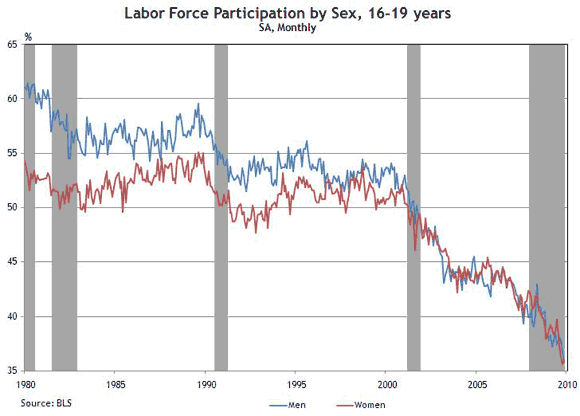

It also appears that the decline in youth participation is most dramatic among teenagers, and for that group it is an equally sized decline for both males and females (see the next two charts).

Because schooling is an important activity for young people, the changing pattern of school enrollment is an obvious potential source of change in the labor force attachment of youths. In fact, the proportion of those between 16 and 24 enrolled in school has risen from about 42 percent in the late 1980s to nearly 57 percent in 2008 (BLS, October supplement to the Current Population Survey).

But being in school does not preclude labor market participation. In fact, increasing school enrollment is unlikely to be the only explanation because the increase in the school enrollment rate this decade is less than last decade. Between 1989 and 1998 enrollment increased from 48 percent to 54 percent whereas it increased from 54 percent to 57 percent between 1999 and 2008.

The big change appears to be that those in school have become increasingly less attached to the labor market. The percentage of school enrollees aged between 16 and 24 who are also participating in the labor market was relatively stable between 1989 and 1998 at around 51 percent. However, labor market participation by those in school declined between 1999 and 2008 from 50 percent to 42 percent. In contrast, labor force participation by those aged between 16 and 24 not enrolled in school has declined only modestly—from 82 percent to 80 percent between 1989 and 2008.

There are economic returns (benefits less costs) to both labor market experience and education. The decreased attachment to the labor market of school enrollees likely reflects, at least in part, factors such as the increased lifetime economic returns to education relative to alternative uses of time. As such, a widening wage premium on education is probably an important influence on youths’ schooling choices, including schooling intensity. An example would be enrolling in educational programs during the summer instead of looking for summer employment.

It would be good news if increasing long-term rewards to engaging intensively in schooling was the important factor underlying the declining labor force participation by America’s youth. Some alternative explanations for the decline could be much more troubling for America’s future.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply