Why are the prices of so many commodities rising in an economy that seems to remain quite weak?

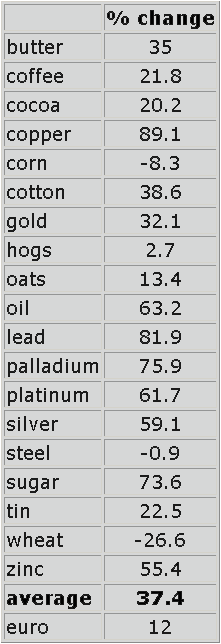

The table below summarizes the percent change between January 6 and November 11 in the cash prices of 19 commodities reported in the Wall Street Journal (downloaded via Webstract). The average commodity in this list has appreciated 37% since the start of the year.

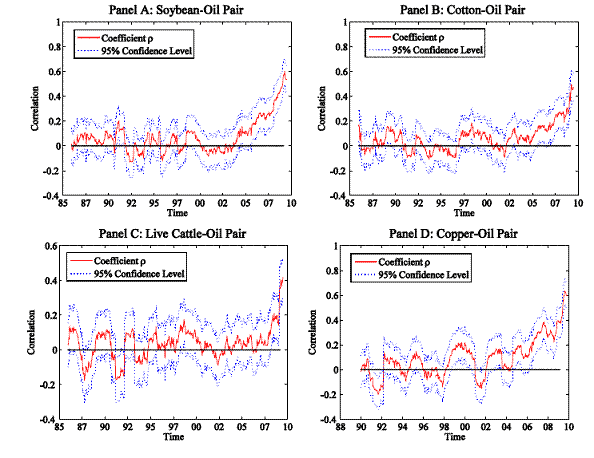

A recent paper by Ke Tang and Wei Xiong documents an increasing tendency for commodity prices to move together over the last few years. A decade ago, what happened to oil prices was largely unrelated to movements in most other commodity prices. The graphs below show how the correlations between oil prices and the prices of four representative commodities have increased significantly over time.

Correlation (using a rolling sample beginning one year before indicated date) between returns on oil and specified commodity. Source: Tang and Xiong (2009).

One explanation I often see in the popular press is that movements in commodity prices are driven by changes in the value of the dollar relative to other currencies. However, the magnitude of movements in commodity prices greatly exceeds the size of changes in the exchange rate. For example, the table above shows that since the start of this year oil prices have increased five times as much as the dollar price of a euro; see also Steve Gordon’s graphs. While the depreciation of the dollar is part of the story, most of the explanation must be found elsewhere.

Another important factor is resurging real economic growth outside the United States, which produces pressures for both the dollar to depreciate and the real price of commodities to appreciate. According to this theory, the increasing correlations between commodity prices results from the fact that countries like China are so much more important for the world economy today than they were a decade ago.

A third explanation is that investors are making increasing use of commodities as an investment class. Although Treasury Inflation Protected Securities offer a hedge against an increase in the U.S. consumer price index, they don’t offer protection for foreign investors against depreciation of the dollar. Insofar as increases in the prices of commodities like oil may depress real economic activity, holding commodities as an investment also offers useful diversification against risks to equities. Particularly when interest rates are low, there is an incentive to hoard physical commodities as an investment vehicle.

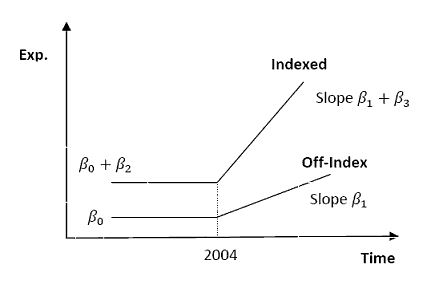

The paper by Tang and Xiong proposes that the increased use of commodities as a financial investment accounts for the increasing correlation among commodity price changes over time. In support of that claim, they note the growing popularity of investment strategies based on the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index or the Dow Jones Commodity Index. Tang and Xiong document that correlations among commodities included in the indexes have increased faster than those not included. For example, one of the regressions they estimate relates the return on commodity i to equity returns, bond yields, the value of the dollar, and oil prices, where the coefficients are allowed to grow with time at different rates before and after 2004, and with different trends on these coefficients estimated for commodities included in indexes as for those excluded. The figure below shows their estimated time path for the coefficient on oil prices comparing the indexed and non-indexed groups.

Coefficient relating return on average commodity to return on oil as a function of time for commodities included in the GS or DJ indexes (top curve) and those excluded (bottom curve). Source: Tang and Xiong (2009).

For any of the explanations in this third class, one of the important challenges is to reconcile the story of commodity speculation with supply and demand for the underlying physical commodity. If we propose that speculators have driven the price of the commodity up, the physical quantity demanded should decline as a result. In order to be sustained, a coherent speculation-based theory of commodity price appreciation requires increased physical storage of the commodity.

The solid black curve in the figure below plots the typical U.S. crude oil stocks (excluding those held in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve) for each week of the year, based on the average over 1990-2007. The red line gives the actual values for 2008, which were significantly below the historical average, particularly in the spring of 2008 when oil prices were rising so dramatically. Those below-normal inventories were one reason I focused on what was going on to the fundamentals of supply and demand in trying to understand the behavior of oil markets in the first half of 2008.

Weekly U.S. crude oil ending stocks, excluding SPR, in thousands of barrels, from EIA. Black line: average over 1990-2007. Red: 2008. Green: 2009.

On the other hand, inventories of crude oil this year, shown in green above, have been substantially above normal, meaning that in the absence of that oil going into storage, we would have expected to see lower oil prices than we currently have.

Moreover, much of the current stockpiling may be taking place outside the United States. For example, Yves Smith noted this story from Bloomberg last August:

Copper, nickel and other base metals stockpiled by speculative Chinese investors including pig farmers may be sold when “market sentiment turns,” said Scotia Capital Inc.

A price surge and easy bank credit this year encouraged pig farmers, stock brokers and businessmen to buy copper and nickel for speculation, Liu Na, an analyst with Scotia Capital, wrote in a note dated Aug. 17, citing reports from the state-owned China Central Television….

“These stockpiles are in ‘weak hands’ as speculators have no real use for base metals,” Liu wrote. “When the market sentiment turns, they are very likely to turn into quick sellers, especially when the bank’s money is involved.”

I also found this November 3 story from the Financial Times of interest:

Gold prices continued to rise on Wednesday extending the all-time highs which followed India’s central bank bought 200 tonnes of the precious metal, swapping dollars for bullion as the country’s finance minister warned the economies of the US and Europe had “collapsed”.

India’s decision to exchange $6.7bn for gold equivalent to 8 per cent of world annual mine production sent the strongest signal yet that Asian countries were moving away from the US currency.

Policy-makers in the Federal Reserve have traditionally thought of inflation as a broad movement in all wages and prices, which to some extent is under their control, and viewed changes in relative commodity prices as outside their control. I believe that this is not the correct understanding of the current situation. Concerns about inflation, particularly on the part of foreign dollar-holders, are likely to show up first in the relative prices of internationally traded commodities. Insofar as these relative price changes can be destabilizing in themselves, it cannot be wise for U.S. policy-makers to ignore them.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply