A week ago, I began my series of posts on the drug business, starting with my perspective on how the business is changing and then moving on to posts on Valeant’s (VRX) business model and the runaway story of Theranos. I am finishing this series with a post on Pfizer’s (PFE) plan to merge with Allergan (AGN) and the economics of the merger. This deal, which will make one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world even larger has drawn attention not just because of its magnitude, but also for its motives. While there is some desultory chatter about synergy (as is the case with every merger), this deal seems focused on two specific motivations: the first is that this is a bid by Pfizer to buy Allergan’s higher growth and the second is that this is a deal designed to save taxes. Not surprisingly, the latter is attracting attention not just from investors and financial journalists, but also from politicians.

Growth but at what cost?

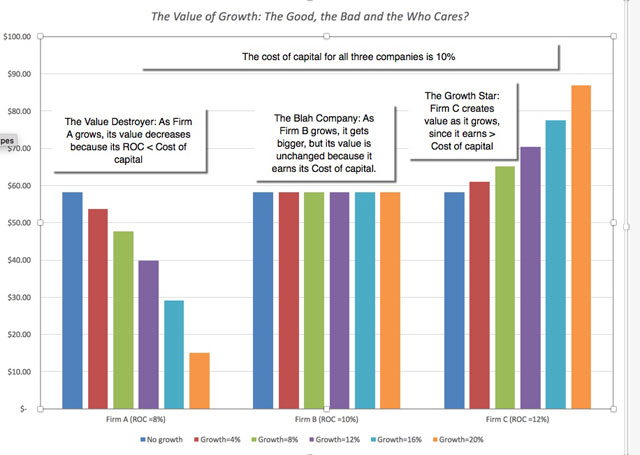

One of the most dangerous maxims in both corporate finance and investing is that it is better to grow than to not grow, and that a company that faces stagnant or declining revenues (and income) should seek out higher growth (at any price). In a post from a long time ago, I looked at the value of growth and noted that the net effect of growth depends on how much you pay to get it, and that overpaying for growth will give you higher growth and a lower value. In the graph below, you can see the effect of growth on value for three companies, all of which grow, the first by making investments that generate returns that exceed the cost of capital, the second by making investments that earn the cost of capital and the third by making investments that earn less than the cost of capital.

It is this perspective on growth that makes me skeptical about companies that grow through acquisitions, especially when those acquisitions are big and are of public companies. Since you have to pay market price plus (a premium of 20-30%) to acquire a public company, for a growth-motivated acquisition to create value, you have to be able to find a growth company that is under valued by more than 20% or 30%, given its growth rate, at the time that you initiate the deal to be able to walk away with value added. Note that, much as I am tempted to do a riff about the wondrous benefits of bringing both Botox and Viagra under one corporate entity, I am deliberately keeping synergy out of the equation since it can justify a premium.

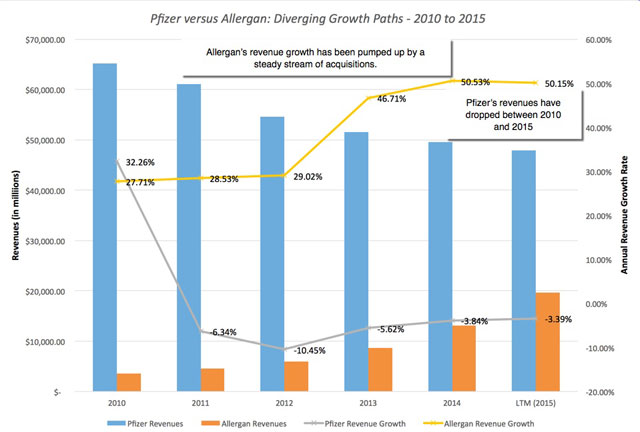

Let’s consider then the proposition that the Pfizer deal for Allergan is driven by the motivation of buying growth. The basis for the story is visible in this comparison of Pfizer and Allergan’s operating numbers over the last five years:

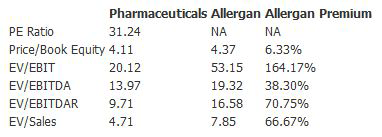

Over these five years, Pfizer’s revenues shrank about 6% a year whereas Allergan’s revenues grew at 40.62% a year. That makes the case for the acquisition, right? Not quite, because it depends on whether the market is already pricing in Allergan’s growth. If it is, buying Allergan will allow Pfizer to grow faster, but not create value and may in fact destroy value if the premium paid is large enough. To examine whether Allergan offers growth at a bargain, I considered valuing Allergan, but very quickly abandoned the idea, because it reminded me of Valeant, insofar as it has grown rapidly through acquisitions, funded with significant amounts of debt and its financial statements are a mess. Thus, while it clear that Allergan has grown fast, the question of whether it has grown sensibly is a question that remains to be answered. Looking at the multiples at which Allergan was trading, prior to the Pfizer bid, there is almost no multiple on which it looks like a bargain.

What is the bottom line? If I were a Pfizer stockholder, I would be concerned if buying growth were the primary reason for this acquisition, since the growth at Allergan is not only at a premium price but also untested (insofar as it is acquired growth rather than organic growth). I would be terrified, especially after recent scares, that the acquisition accounting at the company may be hiding bad surprises.

The Insanity of the US Tax Code

One of the most surprising aspects of this deal is how open the Pfizer management has been about the tax motivations for the deal, with Ian Read, the CEO of Pfizer, saying that “the company is at a tremendous disadvantage under the U.S. corporate tax code and that Pfizer is competing against foreign companies with one hand tied behind our back.” This planned “inversion”, of course, has triggered a heated response, understandable (at least politically), though some of the critics don’t quite understand the US tax law and what exactly Pfizer will gain by leaving behind its US incorporation.

I have vented extensively about the absurdity of US tax law and how it encourages perverse behavior from businesses (and individuals). Rather than repeat myself, let me focus in on the three aspects of the law that makes it so damaging:

- The level of rates: There was a time four decades ago when the US federal corporate tax rate, at 40%, was in the middle of the global tax rate distribution, with many countries adopting a policy of punitive corporate taxation. The corporate tax rate in the US was last lowered in 1986 to 34

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply